Part 1: A memorable introduction

Jimmy Adams

I was an eleven-year-old chess novice and had recently joined the Islington club, which met on Friday nights in the lecture room of a library further down the road from where I lived in north London. The secretary, Mr F.C. Shorter, well into retirement but maintaining an air of authority, suggested that we play a game, undoubtedly with the good intention of teaching me a thing or two about chess. Up to then I had previously only played casual games against other school kids who would drop in to the club for just an hour or two.

And so it was that Mr Shorter held out his clenched hands, I chose the black pawn and he opened 1 d4 – to which I replied, after some thought, 1…f5 But there and then, right from the kick-off, he issued a stern warning to me: “You shouldn’t do that!” and, waving his finger accusingly across the h5-e8 diagonal to alert me to the exposed state of my king, completed the admonition with the words “It’s very dangerous!” However, before I had the chance to consider what

…when Islington club secretary Mr F.C. Shorter utterly condemned my use of the Dutch Defence

I should have played instead, I heard a confident voice adding a couple of words to Mr Shorter’s statement: “. . . dangerous for White !” I looked up and saw a smartly dressed man with a friendly face which was almost, but not quite, breaking into a grin. This, as I soon found out, was Ron Harman. As for Mr Shorter, well, he was clearly taken aback by the affront and, caught unawares, started mumbling “No, no, no. . .” The rest I don’t remember, but what is for sure: I didn’t get mated on that fateful diagonal and from then on I had a very high opinion of Mr Harman – he had stood up for me against no less a figure than the club secretary!

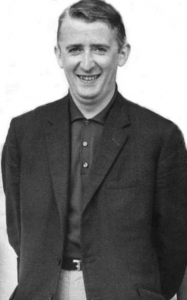

Such was my introduction to Ron’s sharp wit. He was already an experienced chess player when he joined the club in 1958, having competed even at the British Championships that year. He was also well-educated, well-spoken and well-informed. He seemed to be good at everything he did. Whenever he read or heard anything he did not take it at face value, but questioned it, processed it and drew his own conclusions. And though, by his own admission, he had a quick temper which resulted every now and then in some dispute or other, for the most part he gave the impression of being a gentlemanly character who was also fun to be with – provided you could take a joke!

The two Rons

After a while I started to play regularly against the adults and stayed till closing time at 10.30 p.m., long after all the other kids had left. Then, a little later, another Ron joined Islington – Ron Banwell, an accomplished and versatile artist as well as a strong chess player, who had previously played at the venerable West London club, where he had learned a lot from Cenek Kottnauer, one of the country’s best players. He had grown up in boys’ homes and, unlike Ron Harman, had been deprived of a good school education, but, like Ron, he had a high degree of natural intelligence and, moreover, was also practical which made him an ideal team captain. In fact the two Rons, together with Stewart Reuben whose association with the club went back to the early 50s, lost no time in instilling a new sense of vitality and ambition amongst the team members, which in turn attracted a good number of other strong local players and elevated Islington from the bottom division of the London League to the top, making it one of the most feared teams in the whole country. The club’s high point came in the 1966/67 season when Islington not only won the London League ‘A’ Division with a 100% score and the National Teams Lightning trophy, but also the National Club Championship, defeating London, Oxford and Cambridge Universities en route!

“My name is Znosko-Borovsky!”

Ron Harman, like Ron Banwell, was very competitive not only in chess but also when it came to card games, darts, snooker, cribbage, mini-golf, you name it – or even just winning an argument! But whereas Ron Banwell was into painting and drawing, music and photography, brewing beer, cars, travel and the beauties of the countryside, Ron Harman’s preference was for solving crosswords and taking part in quizzes, reading and writing, conversation and debating, news and current affairs, restaurants and clubs, and the pleasures of big city life. Yet, despite their differences, the two Rons became great friends and related to one another, I think perhaps because each of them had to overcome similar difficulties after being separated from their parents in childhood.

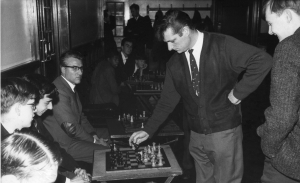

Club champion Ron Banwell giving the traditional annual simultaneous display at the Islington Chess Club in 1964

In the late 50s and early 60s, a few Islington players, including the two Rons and myself, would spend Saturday evenings at the En Passant chess cafe, located on the first floor of an old pre-Victorian building which for over a century had housed the Queen’s Head tavern. Appropriately enough it was situated just across the road from the celebrated Mecca of chess, Simpson’s-in-the-Strand. In its early days, the En Passant was visited regularly by quite a few colourful characters who had been habitués of the famous Gambit chess cafe, which had recently closed down after half a century of service to the chess community. Such a clientèle made for a lively bohemian atmosphere and if you were prepared to pay the hourly rate for a board, set and clock you could play 5-minute chess to your heart’s content until the small hours of the morning. Upstairs was the poker room, reached through a concealed entrance and up a narrow winding staircase.

Wit and humour

I had plenty of opportunities to appreciate Ron Harman’s unique sense of humour.

At one of the Islington club’s annual general meetings the Chairman wanted to make firm arrangements for serving tea and biscuits, and washing up afterwards, as there were no volunteers. But when he proposed an alphabetical rota, Ron spontaneously blurted out “My name is Znosko-Borovsky!” (a well-known chess writer at the time by virtue of this Russian master’s classic work The Middle Game in Chess). “Why didn’t I think of that?” I cursed myself – “Ron will get out of that job and I am first in line because my name begins with the letter A!”

“Just ask where the RFH is!”

I saw with my own eyes an example of the one-upmanship between the two Rons during their individual game in an early 1960s Islington club championship. Whilst play was in progress I looked at Ron Harman’s score sheet and noticed he had signed his customary RFH on the line for the White player, but for the player of the Black pieces, instead of R.E. Banwell, he had written ‘Weak Amateur’ – an even greater put-down than the slightly more acceptable ‘NN’. Some sensitive souls might have been offended by this insult but not Ron Banwell. When I looked at his score sheet, I saw in the Black move column against his opponent’s first move of 1 N-KB3 (we used descriptive notation then) simply the word ‘ditto’. Then alongside White’s second move 2 P-KN3, under his word ‘ditto’, merely the punctuation “. And this carried on until the long-winded Réti/English Opening symmetry had been broken about ten moves later. It was gentle contemptuous humour designed somehow to send a message that though this particular opening demanded he copy his opponent’s moves, they were so routine and banal that they were not even worth spending the time to write down on the score sheet!

Then there was the time when we had to go to the Royal Festival Hall in London for a chess match. I wasn’t sure how to get there, so I asked Ron. He replied “No problem. Just get out of the tube station at Charing Cross and ask where the RFH is!” By the way, Ron’s brother Kenny mentioned that the extra initial ‘A’ which Ron later applied to his signature was fictitious. He only had one other forename, Frederick. But I think there was a good reason he sometimes added this letter to make it RFA Harman. It was in memory of his older brother Alan, who had died soon after birth, a year or so before Ron himself came into the world.

During one of the enjoyable Eastbourne chess festivals organised by B.H. Wood, founding editor of CHESS magazine, I went with Ron to a casino. Here he sat down and made himself comfortable, fully prepared for a long haul at the roulette table. Indeed, Lady Luck seemed to be smiling on him and his winnings began to mount up, although every now and then for some reason he would be fidgeting in his chair. As the evening wore on, however, his pile of chips on the green felt table began to steadily decrease until it was down to zero. Now was clearly the time to leave. However, as Ron rose from his chair to the sound of the croupier’s consolatory words, “Better luck next time, sir!”, instead of heading straight for the exit like any other man of sorrow, he proceeded to the cashier, put his hand in his right pocket and drew out a fistful of chips, then another and another. This process was then repeated in his left pocket. You should have seen the gobsmacked look on the croupier’s face! Now I understood why Ron had been shuffling around so much. You see, every time the wheel had spun in his favour, he had discreetly placed a good percentage of his winnings in his jacket, out of temptation’s way.

Another very good friend of Ron, and indeed other Islington players, was John Ripley, a lovable guy from Liverpool with a great sense of humour. John had spent some time in London in the 60s when he played for Islington, but Ron also met up with him at various tournaments all over the country. In 1968 John was joyfully celebrating an exceptionally fine result at an international tournament in Whitby, finishing as the highest placed British player and with the promise of even greater things to come. However, there was a cruel reality check a little later, after the two of them had returned to Liverpool. Here they were walking down the street when they encountered a poverty-stricken, bedraggled and luckless tramp, begging for a few coppers to buy a hot cup of tea. After duly making a small donation, Ron then turned to John and said: “You see that fellow. He was the highest placed British player at Blackpool 1948.” Again, some touchy chess player might take great exception to this brutal kind of humour, but John just laughed it off.

The Accelerated Dragon and Bobby Fischer

Stewart Reuben was the first Islington player to adopt the Accelerated Dragon, 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6, after which Ron soon followed suit. Then Kenny took the theory and practice of this opening even further, filling a couple of school exercise books with handwritten analysis of the variation. Little wonder that he soon had a higher chess rating than Ron and also developed into a very strong correspondence chess player.

Anyway, one club night, I think in 1963, I said to Ron: “I haven’t seen Stewart for quite a while, where is he?”

“He’s in New York doing research.”

“Oh, what’s he researching?”

“Adhesives – he’s trying to find a solution to the Maroczy Bind !” (At the time this still had a reputation for being almost a refutation of the Accelerated Dragon).

As it turned out, Stewart neither pursued his career as an industrial chemist nor did he completely resolve the problem of the Maroczy Bind, even suffering a severe 17-move defeat many years later against a theoretically well prepared John Ripley in the Hastings Challengers. However he did stick like glue to his chess activities and eventually became England’s most successful tournament and match organiser and the holder of key posts in both the British and International Chess Federations.

“Bobby Fischer sat here . . . and walked off without paying the board charge”

During the time he spent in New York, Stewart wrote a ‘Letter from America’ column for CHESS magazine, which I always looked forward to reading every month. It was here that I first learned of Bobby Fischer’s 11-0 sweep of the US Championship. These reports also included games – even one Stewart had played in a blitz tournament against Fischer with the Accelerated Dragon. But Stewart was not the first Islington player to have this distinction. Three years previously, on his way home from the Leipzig Olympiad, 15-year-old Bobby, accompanied by William Lombardy, had stopped off for a lightning visit to England, during which time he arrived unannounced at the En Passant. As fate would have it, this was on a Sunday afternoon when Ron was there playing cards and he readily accepted the young grandmaster’s challenge to take on all-comers at blitz, conceding time odds of two minutes to eight and playing for a stake of five dollars a game.

One of their encounters featured a queen sacrifice in the Accelerated Fianchetto.

15-year-old Bobby Fischer, accompanied by US grandmaster William Lombardy, arrived unannounced at the En Passant chess cafe in the Strand and took on all comers at blitz

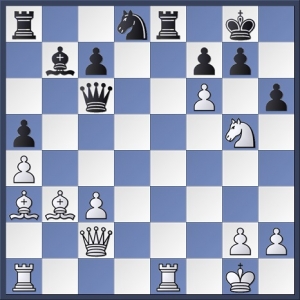

Bobby Fischer – Ron Harman

Blitz challenge, En Passant cafe, London 1958

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Nc3 Bg7 6 Be3 Nf6 7 Bc4 0–0 8 Bb3 Ng4

Not 8…Na5 9 e5 Ne8 10 Bxf7+ Kxf7 11 Ne6! – a trap which Fischer pulled off against Reshevsky a few weeks later in the US championship.

9 Qxg4 Nxd4 10 Qh4

10 Qd1 was later found to be the best way for White to secure an advantage.

10…Qa5 11 0–0 Bf6

12 Qxf6!?

In deciding on this committal move, Fischer spent 30 seconds, which, in view of the time limit, had a direct bearing on the eventual result of the game. But what is remarkable is that this sacrifice only became known to the chess world at large four years later when Nezhmetdinov won a brilliant game with it in Russia.

12…Ne2+ 13 Nxe2 exf6 14 Nc3 d5

Giving up a couple of pawns to free lines for his pieces and rapidly complete his development.

15 Nxd5 Be6 16 Nxf6+ Kg7 17 Bd4 Kh6

The game now continued 18 h4 Rfd8 19 Bc3 Qb5 20 g4 but Fischer lost on time some moves later in a very unclear position.

They played four games in all. Fischer won 3-1.

After the blitz session had finished and Fischer had left, a note was attached to the chair on which he had been sitting. It read: “Bobby Fischer sat here . . . and walked off without paying the board charge. Lesser folk will not be treated so lightly.”

The Islingtonian

In this same period Ron launched an excellent club bulletin, The Islingtonian, but became disillusioned with the lukewarm response from members. Thus, when he wrote a humorous ‘Who’s Who’ on himself, in a subsequent issue, he sent an unambiguous message – Greatest Ambition: “To sell a magazine.” Greatest Achievement: “He managed to give one away.” By the way, Ron also wrote short stories, designed for popular main line magazines, but he became too easily disheartened when encountering rejections from publishers.

“Ron had an elegant style of play, which was in keeping with his equally elegant appearance”

Subsequently, Stewart took over the task of producing The Islingtonian which, apart from documenting the latest successes of the club, became an important permanent record of the early Islington Congresses of the 60s, of which he was the chief organiser. However Ron did not give up on chess journalism and later took on the role of games annotator for the Middlesex Chessletter, which incidentally I edited in the early 70s as I did the bulletins of Stewart’s later Islington Congresses, which regularly attracted well over a thousand competitors.

Ron had an elegant style of play, which was in keeping with his equally elegant appearance and the gold pen with which he scored his moves in immaculate handwriting. He seemed to absorb knowledge of the openings effortlessly. Even after playing through a handful of games with some particular variation he would grasp the essentials and then just apply them immediately in practice, without further study. Such was the case in this game with the Anti-Marshall . . .

Phillips and Drew 1980: Stewart Reuben (front row extreme right with his mother) followed up his 1000-player Islington chess congresses by organising three major grandmaster tournaments at County Hall, Westminster, and then the Karpov-Kasparov world title match at the Park Lane Hotel

R.F. Harman – K.O. Ballard

London League 1965/66

(Notes by Ron Harman in The Islingtonian)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 0–0 Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 0–0 8 a4

The Anti-Marshall Attack.

8…Bb7 9 Nc3

Leonard Barden says this is bad after 9…Nd4. Personally I feel happier in the resultant positions than those arising after the standard 9 d3.

9…b4

This plan combined with Black’s next seems quite promising as he should always obtain good play for the sacrifice of the b-pawn. In his haste to avoid material loss Black mistakenly exchanges on move 11.

10 Nd5

10…a5

The alternative 10…Nxd5 was played in R.F.Harman – T.Guttridge, Spalding Open 1968, which continued 11 Bxd5 d6 12 d4 Bf6 13 c3 Rb8 14 a5 bxc3 15 bxc3 Ne7 16 Bxb7 Rxb7 17 Qd3 Qa8 18 Ba3 exd4 19 cxd4 Nc6 20 e5 Be7 21 Qc3 Rb5 22 Rec1 Nxa5 23 Qxc7 Qb7 24 exd6 Bf6 25 Qxb7 Rxb7 26 Rc7 Rfb8 27 Rac1 Rb1 28 d7 Rxc1+ 29 Bxc1 Rd8 30 Ne5 Be7 31 Bd2 Nb3 32 Nc6 1-0.

11 c3 bxc3 12 bxc3 Re8

Better was….d6 immediately. The text weakens f7.

13 Nxe7+ Qxe7 14 Ba3 d6 15 d4! Qd7

All lines commencing 15…exd4 16 e5 were very much in White’s favour.

16 Ng5 Nd8 17 dxe5

17…Rxe5

Better was 17…dxe5. I had been analysing 18 Qc2 h6 19 Rad1 Qg4 (19…Qc6 20 Rxd8 hxg5 21 Bd5 seems good for White) 20 Rxd8 Qxg5 21 Rxe8+ Rxe8 22 Bxf7+ Kxf7 23 Qb3+ winning a pawn. As this line did not come about I did not check whether these continuations were watertight.

18 f4 Re8

A good try seemed to be 18…Rxg5 19 fxg5 Nxe4.

19 e5

19…Qc6

If 19…dxe5 20 fxe5 Qxd1 21 Raxd1 Ng4 22 e6.

20 Qc2

Black overlooked this move. White threatens to get in on the mating season himself.

20…dxe5 21 fxe5 h6 22 exf6

22…Rxe1+

If 22…hxg5 23 Be7! and if 23…gxf6 24 Qg6+. Then White can follow with Re3 or Re5.

23 Rxe1 hxg5

24 Bd5!

Several moves are good enough here but as Black can wriggle with….Ne6 White chooses the most forcing continuation. Of course, if now 24…Qxd5 25 Re8 mate.

24…Qd7

If 24…Qb6+ 25 Kf1 Ne6 26 Bxe6 fxe6 27 Qg6.

25 Re7

This forces 25…Qxe7 Also playable was 25 Qg6 Ne6 26 Bxe6 fxe6 27 Be7.

1-0

* * * *

“How to be a good club-member: Do NOT attend club nights.”

The following satirical piece is taken from a 1965 issue of The Islingtonian and summed up the problems Ron had encountered when dealing with club members over the years. It was rare that his humour turned into something so bitter, but he had good reason to complain about the lack of cooperation he received. Stewart Reuben also made a similar complaint when organising the early Islington Opens, the notable exception to any such criticism of course being Ron, who would do anything from acting as treasurer, writing up score charts, doing pairings, setting up chess sets – and even serving refreshments!

How to be a good club-member ?

1. Do NOT attend club nights.

2. If you do come, come late and/or leave early.

3. Never come in bad weather.

4. If you attend a meeting, criticise officers without justification.

5. Never accept office, as it is easier to criticise than carry out.

6. Get very annoyed if not appointed to Committee, but if you are, remember not to attend meetings.

7. lf asked to give an opinion by the Chairman regarding an important issue, feign dumbness or ignorance. After the meeting tell everyone your opinion on that very issue and how it should be tackled.

8. Do nothing more than absolutely necessary, but when other members roll up their sleeves and unselfishly use their ability to help matters along, howl that the club is being run by a clique.

9. Hold back your club subscription or do not pay it at all.

10. Do not bother about recruiting new members, but when others make the effort complain that outsiders are pinching your place in the team.

11. When the club spends any money tell everybody that the money is being wasted on (a) inessentials (b) luxuries or (c) inferior equipment.

12. If asked to advise on club spending or policy, refuse modestly; if not asked, resign from the club.

13. Do not tell the club how it can help you, but if it does not manage to read your mind and help you, resign from the club.

14. If other club members interfere when you are trying to play five-minute chess and succeed in saving you smashing yet another club-clock, resign from the club.

15. If you are interested only in yourself and are prepared to enjoy the maximum amenities for the minimum amount of effort and expense, stay in the club, because, brother – you’re in the majority.

From Monte Carlo to Raymond’s Revue Bar

Around this time Ron worked for a firm of accountants, King and King, still practising today in the West End of London. The boss, Syd Kalinsky, was no mean chess player and regularly occupied a high board in the Essex county team. Furthermore he was happy to employ good standard chess players in his business and field strong teams in the London Commercial League and other Cup competitions. In fact such was the success of King and King that they were even dubbed ‘a team of chess players whose hobby is accountancy’! Another employee, Danny Wright, became one of the highest rated of all Islington players and not only won the Hastings Challengers in 1967/68 but also performed creditably against the grandmasters in the Premier the following year. He even defeated many times British Champion, Jonathan Penrose, on top board in a Middlesex v Essex county match a little while later. Incidentally, Ron and Danny, as well as other strong Islington players Gerald Bayliss, Paul Mercer, Kenny Harman and John Bennett all attended Dame Alice Owen’s School in Islington, which was a veritable hotbed of chess talent in those days.

Ron did not play abroad very much. However, after competing in the Monte Carlo Open in 1967, I told him what a glamorous tournament it was, and he and other Islington players, Stewart Reuben, Jonathan Enticknap and John Bennett took part the following year and with some success.

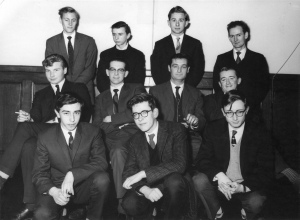

Back row (l to r): George Wheeler, Kenny Harman, Gerald Bayliss, Gareth Thomas

2nd from back row (l to r): Paul Mercer, Michael MacDonald Ross, Ron Banwell, Ron Harman

Front row (from l to r): John Bennett, Jonathan Enticknap, Danny Wright

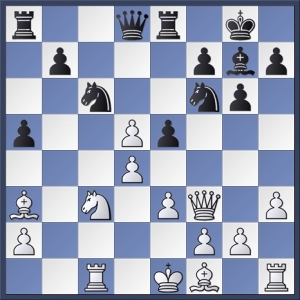

K. Tuomainen – R.F. Harman

Monte Carlo Open, 1968

(Notes by Kenny Harman in Middlesex Chessletter)

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Nf3 Bg7 5 e3 0–0 6 b4 a5

Pachman considers the manoeuvre initiated by this move to be dubious for Black.

7 b5 c5 8 bxc6 Nxc6 9 Ba3 Re8 10 Rc1

10…Bg4

Completing Black’s development and threatening….e5 Curiously this move is not discussed in Pachman’s Indian Systems.

11 h3

11 Be2 seems preferable, the text is neatly refuted.

11…Bxf3 12 Qxf3 e5! 13 cxd5

13…Nxd4! 14 Qd1

If 14 exd4 exd4+ 15 Ne2 Nxd5 and Black has an overwhelming position.

14…Nxd5 15 Nb5?

White’s only remaining chance was by 15 Bd3 and 16 0–0.

15…Nxe3!! 0–1

If 16 fxe3 Qh4+ 17 Kd2 Qf2+ and wins easily.

On their return journey from Monte Carlo, Ron told me that John Bennett had gone off somewhere in Paris and was never seen again, even though he had been a regular member of the Islington club for quite a few years. Did some terrible fate befall him in the Latin Quarter? Did he meet a beautiful French girl on the banks of the Seine, and give up chess for ever? Nobody ever found out and his disappearance remains a mystery to this day.

After some years Ron left King and King to take up gainful employment at Raymond’s Revue Bar, Soho’s highest-profile strip club. “Being a poker player this is not without certain risks,” Ron joked – or maybe he was being serious. However, he did find the accounts there hard to handle and after a while decided to take a break from London life and return to Southport, where he had been evacuated during the war, and re-connect with relatives up north. At the beginning of the 70s, for various reasons, other strong players too started to drift away from Islington, mostly to the rapidly expanding London Central YMCA and Cavendish clubs, although Stewart Reuben remained loyal to Islington, where he strengthened the team by the addition of a new top board in Simon Webb, author of the popular Chess for Tigers, and where George Goodwin opened a whole new chapter in the club’s history, as well as that of the whole country, by staging monthly rapidplay tournaments at Highbury Grove School. This, coincidentally, was also my old school, although, unlike Owen’s, in the years I was there the boys at Highbury were highly vulnerable to Scholar’s mate and never got around to competing against juniors from other schools.

After some years Ron left King and King to take up gainful employment at Raymond’s Revue Bar, Soho’s highest-profile strip club. “Being a poker player this is not without certain risks,” Ron joked – or maybe he was being serious. However, he did find the accounts there hard to handle and after a while decided to take a break from London life and return to Southport, where he had been evacuated during the war, and re-connect with relatives up north. At the beginning of the 70s, for various reasons, other strong players too started to drift away from Islington, mostly to the rapidly expanding London Central YMCA and Cavendish clubs, although Stewart Reuben remained loyal to Islington, where he strengthened the team by the addition of a new top board in Simon Webb, author of the popular Chess for Tigers, and where George Goodwin opened a whole new chapter in the club’s history, as well as that of the whole country, by staging monthly rapidplay tournaments at Highbury Grove School. This, coincidentally, was also my old school, although, unlike Owen’s, in the years I was there the boys at Highbury were highly vulnerable to Scholar’s mate and never got around to competing against juniors from other schools.

I confess I’m drunk, but this is great. Thanks for it.

Jimmy,

Thank you for that tribute to Ron; one of the great pleasures that chess has given me is to meet many interesting and intelligent people – he was certainly one of those. I left London in 1964, but I well remember the Islington club and its many characters, including yourself. Another who springs to mind is William? Poutrous, an Iraqui I believe, and very opinionated.

You may remember me as one of the Cedars players from Harrow, headed by David Rumens. Only David Levens and myself still play at a low level.

Best wishes, John Collins.

Very accurate account of Ron given above! I enjoyed his article on how to be a good chess club member! excellent.

15. If you are interested only in yourself and are prepared to enjoy the maximum amenities for the minimum amount of effort and expense, stay in the club, because, brother – you’re in the majority.

So true of so many club moochers…I mean players.

A lovely tribute to Ron who was the heart and soul of Cavendish Chess Club for many years after his Islington Days.

Cavendish is still home to Danny Wright, Stewart Reuben and of course our president, Syd Kalinsky. Ron’s brother Kenny also played for us a few years ago. Ron was the much loved editor of the club newsletter which flew off the shelves as much for the Shakespeare quotations and the potential libel actions as for the chess content.

There are many stories about Ron , in fact never a dull moment. He was equally happy swapping stories with a grandmaster or a palooka … “he walked with kings nor lost the common touch”. I always found him very good company though hid did follow some of his own club rules by resigning at regular intervals over some intolerable injustice.

One story I recall is of Ron’s 2nd appearance on the TV Quiz, 15 to 1. The rules did not allow a second appearance so he changed his name to Chris this time. Ron claimed that he was timed out and eliminated because he forgot to answer a question directed at Chris!

I also recall winning maybe the first Islington Open at the En Passant in the mid 60s and being approached by this unknown kid challenging me to play a five-minute game for my prize money. The kid turned out to be Kenny Harman and I sensibly declined the challenge.