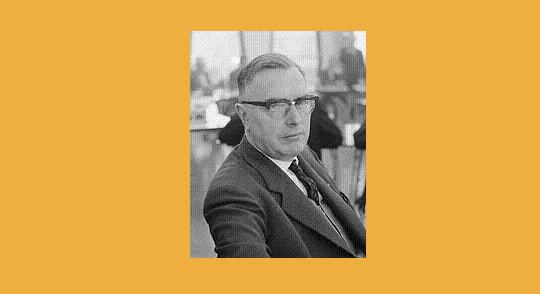

‘I have probably made more silly blunders than any other world champion.’

‘During my chess career, I have made quite a few oversights. In fact I have probably made more silly blunders than any other world champion. Although I remember these errors very well, I am not going to tell you about any one of them here. The blunder I am going to speak of was caused by a sort of oversight, it is true, but it is interesting on the one hand by the indirect way it led to the loss of the game and on the other by the results that it had in my chess career.

It was in the Candidates’ Tournament at Zurich in 1953. I was fifty-two years old then. I had not done very well in that year’s tournaments nor in the immediately preceding ones, and this Candidates’ was my last attempt to regain my place among the very top chess-players of the world. I had prepared myself thoroughly for the contest, and the early rounds of the tournament had gone very smoothly for me. I had won from both Kotov and Geller in wild combinative games. I was feeling like a newly born hero when, in the third round, I was seated opposite Smyslov. When one is in such a mood, everything succeeds. In our game, I had chosen an enterprising opening, and during the middle game I had sacrificed the exchange.

During this game, things were looking rosier than ever. While I was walking around the room, one of the contestants asked me: ‘You are not going to win all your games, are you?’ ‘I don’t think so,’ I replied, ‘but today’s game seems to be going all right.’

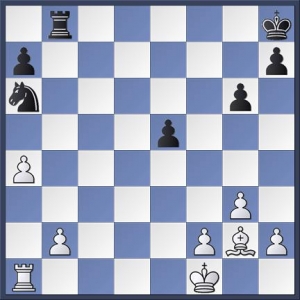

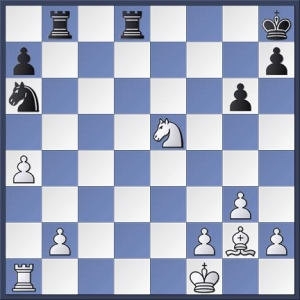

This is the position we reached after twenty-seven moves.

I was playing White, and it was my move.

Euwe v Smyslov

Obvious now is 28 Qd6.

I looked at the consequences. The threat is 29 Qf6+ (and 30 Nxb8) or 29 Qf6+ Kg8 30 Bh3 and Be6 mate.

If Black plays 28…Rb6, then White’s answer is 29 Qe7 and 30 Nf6.

Furthermore, after 28…Rbc8, White continues 29 Qf6+ Kg8 30 Bh3 Qa6+ 31 Qxa6 Nxa6 32 Nf6+, winning back the exchange with a sound pawn to the good.

It did not take me much time to see that after my 28 Qd6, Black’s best procedure would be to exchange queens: 28…Qa6+ 29 Qxa6 Nxa6 30 Nxb8 Rxb8.

I looked at this ending for a few minutes: a pawn up; bishop against knight. My prospects were excellent, but doubtless against a tough end-game players like Smyslov, there would still be some hard work to do.

This was my first appraisal of the position. Then I began to examine other moves, hoping to find something still better.

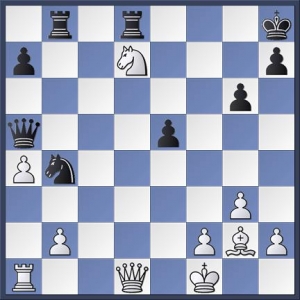

28 Qd2 seemed very solid since it made possible to maintain the knight on the outpost at d7. Moves such as Rd1 and Bh3 would strengthen the knight on its outpost and after that, I could perhaps continue the attack. On the other hand, I was the exchange down in return for one pawn. Against Smyslov this could lead to an unhappy result.

28 Qd2 seemed very solid since it made possible to maintain the knight on the outpost at d7. Moves such as Rd1 and Bh3 would strengthen the knight on its outpost and after that, I could perhaps continue the attack. On the other hand, I was the exchange down in return for one pawn. Against Smyslov this could lead to an unhappy result.

Only one pawn for the exchange? Couldn’t I get more? I again looked at my first line and calculated: 28 Qd6 Qa6+ 29 Qxa6 Nxa6 30 Nxe5, threatening both 31 Nf7+ (forking king and rook) and 31 Nc3 (two rooks).

This looked fine. But Black could answer 31…Rd2, which is rather troublesome. This variation was rather disappointing. so I returned to my 28 Qd2 line, and herein lay my grave error. I quite FORGOT that in the first line with 28 Qd6 Qa6+ 29 Qxa6 Nxa6 I could regain the exchange by simply playing Nxb8. My analysis of Nxe5 instead of Nxb8 had so fascinated me that it had overshadowed and obliterated my original calculation.

This looked fine. But Black could answer 31…Rd2, which is rather troublesome. This variation was rather disappointing. so I returned to my 28 Qd2 line, and herein lay my grave error. I quite FORGOT that in the first line with 28 Qd6 Qa6+ 29 Qxa6 Nxa6 I could regain the exchange by simply playing Nxb8. My analysis of Nxe5 instead of Nxb8 had so fascinated me that it had overshadowed and obliterated my original calculation.

Some five minutes later, I decided in favour of 28 Qd2 … and lost the game in the long run.

This choice of the wrong line was very grave in its consequences. Having lost this game, I began losing others. My optimistic winning mood faded away. I lost my grip on the play and slowly dropped back in the tournament. I have never again participated in a Candidates’ Tournament.

It is very rare that a player forgets the outcome of a variation he has already calculated correctly.’

from a BBC radio broadcast transcribed in Terence Tiller (ed.), Chess Treasury of the Air (Penguin, 1966), pp.253-5.