April 1981 was a fast month for news. John Hinkley had been arrested for the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan. There were riots on the streets of London. Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, went on trial. The Sun newspaper revealed to a rapt nation that American singer Neil Sedaka had ‘lost 40lbs – and gained a lot of new fans’.

But only one story captured the imagination of the British public: the dramatic kidnapping of train robber Ronald Biggs. The affair, which dominated the headlines for six weeks, left one chess player with the toughest defence of his life.

How I Saved Ronnie Biggs

David Levy

On the night of 8 August 1963 a gang of men stopped and robbed a mail train travelling from Glasgow to Euston station in London. They stole mail bags containing £2.6 million in used bank notes. This was by far the biggest robbery in the country’s history. The amount was so huge that even the 10% reward seemed enormous. I was a junior chess player at the time, competing in the British Boys’ under 18 Championship in Bath. Just like everyone else in the country I was astounded by the audacity of the gang. But I never dreamed that, years later, my life would be affected in a major way by the infamous events of that night.

Finding Ronnie Biggs

How does a chess professional come to meet the most famous of the Great Train Robbers, Ronald Biggs, to befriend him and to be the person responsible for flying him out of Barbados in April 1981, back to his home in Rio de Janeiro from where he had been kidnapped?

What turned out to be the greatest adventure of my life began in late 1977. At the time I had been making my living mostly as a chess professional and author. I was in the chess publishing business in a very small way with my business partner Kevin O’Connell. I had written a number of chess books and had conceived and edited the the first ever instant book on a World Championship match, Gligoric’s book on Fischer-Spassky in 1972, which was a chess best seller. (Copies had been flown across the Atlantic and delivered to the American publisher Simon & Schuster within four days of the end of the match.) But it was clear to me by 1977 that chess publishing was not going to be the best business idea since sliced bread and so I was eager to think of more profitable avenues for our business.

Whilst lying in bed one night I got the idea of publishing the autobiography of someone really famous, but why would someone famous want to have their autobiography published by a tiny business run by a couple of chess players? Answer – they wouldn’t . . . unless there was something exceptional about the subject that made it difficult or undesirable for them to deal directly with a big publisher. My idea was not to print and distribute such a book ourselves – we were simply not geared up enough to handle anything much bigger than chess books. Instead we would ‘package’ the book – solicit the source material, edit it, and then contract with a major publisher who would print and market the book.

I thought of three people whose life stories I believed would be of great general interest if told by themselves. One was Princess Margaret – she would not need the money but I naïvely thought that she might like to dish the dirt on the Establishment in revenge for the way she was prevented from marrying her true love, Group Captain Peter Townsend. Another idea was the Shah of Iran. He too was not exactly short of a few quid, but perhaps he would like the idea of telling his own life story. And then there was Ronnie Biggs, the Great Train Robber and prison escaper, who was living in Brazil and still wanted by the British police.

With no way that I could see to make contact with Princess Margaret or the Shah, I decided to do a little research on Ronnie Biggs. I checked the British Library catalogue to see if any books had been written about him and, sure enough, there was one by a Colin MacKenzie. I bought a copy and read it in a few hours, noting down the name of every one of his friends from the time he had arrived in Rio de Janeiro. Armed with this list I took a taxi to the Brazilian embassy in Mayfair where I was able to look up the Rio telephone directory. About half a dozen of the names on my list could be found in the telephone book and I copied their addresses and phone numbers, not knowing how many of them, if any, would still be at the same address. Back at home I wrote my first letter to Biggs. I explained who we were and asked if he might be interested in my idea. I sent copies of the letter together with an accompanying note to each of the names I had found in the phone book, asking for my letter to be forwarded to Ron. I did not receive a single reply.

At the time I had recently started work on a consultancy contract for Texas Instruments. The company was developing a home computer called the 99/4 and I was contracted to advise on writing a chess-playing program for their product. The contract ran for about 18 months, during which time I had to travel to a TI facility in Lubbock, Texas, 11 times. (Small town, friendly people, most famous for being the home of Buddy Holly whose statue adorns the town centre.) But first and foremost I was still a chess professional and thus I was invited to South Africa to compete in two tournaments in April 1978. (Fascinating trip. Went down a gold mine, went down a diamond mine and was given an escorted tour of Soweto. Won a lively miniature against David Friedgood in Pretoria, published in Chess Informator.) As it happened my visit to South Africa was to be followed, almost immediately, by one of my trips to Lubbock. While investigating the various routes from Jo’burg to Texas I discovered that I could make the journey with a stopover in Rio at virtually no extra cost! And so, even though I had received no reply to my letter a few months earlier, I resolved to spend three days in Rio and to try to find Ronnie Biggs.

I did not go empty handed to Brazil. From MacKenzie’s book I had learned that one of the things Biggs missed most about England was Bird’s custard! I have always hated the stuff but I decided that if that’s what he liked then that was what he must have. My hosts in Pretoria, Len and Glenda Schwartz and their four children, had been wonderful. When I told Glenda the reason for my visit to Rio and about Biggs’ love of Birds’ she scoured the local supermarkets to find the biggest tin of custard imaginable. I knew nothing about the food import laws in Brazil and was therefore unsure whether I would be allowed to take the tin into the country, but I resolved to try. I need not have worried because, as I later learned, there would have been an easy way of convincing the customs officers at the airport to allow in almost anything. As it was I sailed through customs without any need to resort to bribery.

The weekly Pan Am flight from Jo’burg to Rio was non-stop and neatly coincided with the day I wanted to travel. I had booked a room at the Intercontinental, almost on the beach at one end of the city. No sooner had I checked in than I unearthed my list of names and telephone numbers. I called them all. Some had recalled receiving my letter and one or two said they had passed it on to Biggs but had heard no more about it. None of them knew his current address or if he had a telephone. I was given one lead, however. The name of a woman who worked on the Brazil Daily, the local English language newspaper. She had an address for Biggs in a village called Sepetiba, down the coast about two hours’ drive from Rio. So I asked the hotel to arrange a car and driver for the following day.

In the morning we set off for Sepetiba and arrived there around noon. With my driver’s help it was not difficult to locate the address I had been given and I was soon walking up the path towards Biggs, who was in the garden washing some clothes by hand (his four-year-old son Michael’s underwear, he explained). I introduced myself and was slightly taken aback by his reply: ‘Did you get my letter?’ It turned out that Biggs had received my missive and had written a reply which a friend, who was returning to England, had promised to post when he landed. Biggs told me that his reply had been positive.

Ronnie Biggs is an extremely affable man and very good company. He has an  excellent sense of humour and almost anyone would find him an extremely pleasant and interesting companion. Within a few minutes we were splitting a beer and within the hour we were having lunch, together with my driver, in a local eaterie. This was not exactly food in the style of the Rio Intercontinental but it tasted good, especially when washed down with a few beers.

excellent sense of humour and almost anyone would find him an extremely pleasant and interesting companion. Within a few minutes we were splitting a beer and within the hour we were having lunch, together with my driver, in a local eaterie. This was not exactly food in the style of the Rio Intercontinental but it tasted good, especially when washed down with a few beers.

Before long we started talking business. Biggs explained to me his unique status. He was allowed to stay in Brazil, despite the extradition requests of Her Majesty’s Government, because he had a Brazilian dependant – his son Michael. It was Biggs’ great fortune that, while he was in jail in Rio in 1974, awaiting the attempts of Superintendent Jack Slipper to take him back to England, he learned on the same day of this Brazilian law and of his girlfriend Raimunda’s pregnancy. But even though he was allowed to live in Brazil Biggs was not permitted to work, so he had survived by way of fees from journalists eager to interview him and handouts from tourists who wanted to dine out on the story of how they had met the Great Train Robber. This hand-to-mouth existence meant that my proposition was quite attractive to him. Any income he received from the publication of a book would be most welcome.

The hours slipped by and we had to go to collect Michael from school. He was a lovely little boy and Ron was completely devoted to him, and Michael to his dad. I do not think I have ever seen such a close father and child as in the brief period between Michael coming home from school that day and my leaving Sepetiba. I agreed to meet Ron at my hotel the following morning to take our discussions further.

How to Write a Book

My idea was this. I would research his life as best I could, using the resources of the Newspaper Library at Colindale. To this end Ron spent a few hours the following day, sitting in the luxurious surroundings of the Intercontinental, drinking and reminiscing. At first it was beer again. But then he introduced me to the Caipirinha, a cocktail made of a Brazilian firewater called Cachaça mixed with the juice of a lime and sugar. And then another. And another. By the time I could not face another Caipirinha I had a mass of notes dictated by Ron about his life before the train robbery. He gave me approximate dates of previous crimes, leads to his court appearances for some of those crimes, information about his personal life, . . . all of it useful as a basis for the serious research necessary for the next stage of the work. I knew that I would be playing on the Scottish team in the Buenos Aires Chess Olympiad that October/November so I agreed with Ron that Kevin O’Connell and I would visit Rio after the Olympiad, with a tape recorder, interviewing him until we had everything he could think of that might make good reading.

Once I was back home in London I followed up every lead Ron had given me. I made photocopies of dozens of newspaper articles about him, going back as far as some of the petty crimes of his youth. I reread Colin MacKenzie’s book from which I gleaned a lot more and I researched some of the facts MacKenzie had published that were new to me. By the time Kevin and I arrived in Rio in mid-November I had a card system, filed chronologically, with one question or fact per card.

Kevin and I spent three thoroughly enjoyable weeks in Rio. Every morning Ron would appear at the Intercontinental around breakfast time. For most of the day we would sit on the balcony of our hotel room, sipping beer and going through the questions and facts on the cards, one by one. We used the cards to prompt Ron and just let him talk. He was a fine raconteur with a prodigious memory for detail and we filled dozens of cassette tapes with his outpourings. For me one of the most interesting aspects of what he had to say was his thinking on crime, punishment and the law. Many of Ron’s comments seem obvious now – prison being the best possible place to learn how to steal; barristers accepting briefs and entering ‘not guilty’ pleas for clients they knew to be guilty (‘. . . after all, how would an honest window cleaner earning £500 a year come to be driving a flashy new white Jaguar and paying his silk £10,000 to defend him?’). Ron also had some insights on juries: ‘Many jurors don’t know what day of the week it is yet they have the power to send a man to jail for life. Juries should be made up of professional jurors who have the ability to think and analyse the evidence.’

We would stop for lunch, always taken in the lush tropical garden restaurant at the hotel, and then in the evenings we would usually go into the centre of Rio where often we would meet up with Ron’s girlfriend of that time, Ulla Sopher. We would dine in the open air, mostly at a churrascaria, a restaurant where barbecued meat is paraded on skewers to all the guests – point to what you like and the waiter manoeuvres it off the skewer and on to your plate. Ron had brought Michael to Rio where the boy would be looked after by John and Lia Pickston, an English couple. The Pickstons were kind and totally loyal to Ron and they doted on Michael. We also met another of Ron’s good friends – a German called Armin Heim, also very loyal.

The Biggs tapes were transcribed by a friend of mine from my Glasgow days, Margaret Fitzjames. She had typed a number of my chess books but, not surprisingly, she found Ron’s story much more interesting than the Dragon Variation of the Sicilian Defence. In those days word processors were a thing of the future. Margaret would type, Kevin and I would edit, then we would use scissors and Sellotape to produce the next draft for Margaret to type. After only two or three iterations we had something resembling a book, which we sent off to Ron for his perusal.

The next stage was for Kevin to return to Rio for a few days, to sit with Ron and  go through the typescript for corrections and additions. Pretty soon we had the typescript in its final form. Shortly after Kevin returned to London we received a letter from Ron telling us about someone he had met, a Scots Guardsman called John Miller, and how he had later discovered that the purpose of Miller’s visit to Rio was to kidnap Ron, put him in a big sack marked as though it held an anaconda, fly him by private plane to the city of Belem which lies at the mouth of the Amazon, thence to transport him by yacht to a Caribbean island from where he could be extradited to London. It all sounded rather far fetched but, fortunately, Ron had suspected that Miller was up to no good and the police had been brought in, with the result that Miller had left the country rather quickly.

go through the typescript for corrections and additions. Pretty soon we had the typescript in its final form. Shortly after Kevin returned to London we received a letter from Ron telling us about someone he had met, a Scots Guardsman called John Miller, and how he had later discovered that the purpose of Miller’s visit to Rio was to kidnap Ron, put him in a big sack marked as though it held an anaconda, fly him by private plane to the city of Belem which lies at the mouth of the Amazon, thence to transport him by yacht to a Caribbean island from where he could be extradited to London. It all sounded rather far fetched but, fortunately, Ron had suspected that Miller was up to no good and the police had been brought in, with the result that Miller had left the country rather quickly.

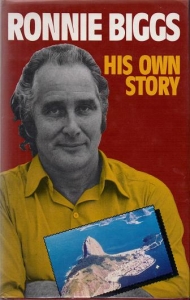

The book was offered to a few publishers before Michael Joseph snapped it up. This London-based publishing house had built part of its reputation on biographies of the controversial. The book started its way through the normal in-house editing and production processes, with publication due for early April 1981.

Kidnapped

One day in mid-March 1981 Kevin and I were working quietly in our office (Kevin’s flat in West Hampstead) when I received a phone call from Armin Heim in Rio. Ron, it seemed, had gone missing, under unusual circumstances. He had left Michael with the Pickstons for the evening while he had gone to meet someone. Ron had not returned to collect his son which, Armin said, he would never have failed to do unless he had been involved in an accident or something similar. Armin thought that something was amiss and that Ron might have been kidnapped. He and the Pickstons had contacted the police who knew nothing and there had been no reports of Ron from any of the local hospitals.

As I put down the phone I recalled the letter Ron had sent me, late in 1978, about the attempt to kidnap him. I rang Heim back and told him what I remembered – that Miller and his associates had planned to take Ron by private ‘plane to Belem and then to one of the Caribbean islands, a former British colony, from where extradition would not be a problem. I suggested to Heim that he tell the police about this plan and ask them to search Belem and the sea nearby for any sign of a yacht or other boat that had recently left Belem travelling north. The following day I heard back from Heim. Yes, a boat had been seen heading north from Belem. A Brazilian navy vessel had given chase but had been outrun. Heim was certain by now that Miller had succeeded and that Ron was heading back to an English jail.

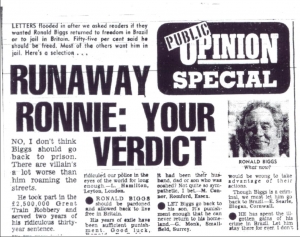

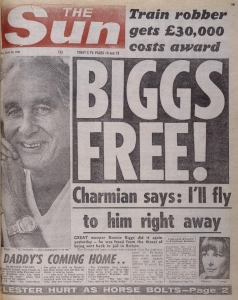

Before long the news broke in the British media that Ron was indeed on his way to Barbados where John Miller’s men would hand him over to the authorities. Kevin and I eagerly watched every news programme on TV. The prognosis was not good – Barbados had an extradition treaty with Britain and the formalities would not take more than a few weeks to complete. When the yacht ‘Now Can I’ reached Barbados we watched as Ron was taken off the boat by the police. I had a feeling of utter helplessness and great sadness, recalling the sight of Ron, the loving father, with Michael on that day in Sepetiba and thinking that the boy, now six, might never see his dad again.

The day Ron was taken ashore in Barbados, 24 March, the telephone hardly stopped ringing. There were calls from Armin Heim, from Lia Pickston, then Armin again, then Lia again, and so it went on. ‘What can we do?’ was repeated again and again. I had been in touch with the editor at Michael Joseph who was responsible for the book. Publication was due in early April and the publisher was sympathetic to my request to speed up the advance payment due on publication. Kevin and I realised that if anything was to be done to help Ron, although we could not imagine what it might be, money would be required. And then came a suggestion. Armin Heim called me to say that he had the name of a brilliant lawyer in New York, David Neufeld, and would I contact him and see if there was any hope of saving Ron in the legal process that was about to commence in Barbados.

The kidnapping exercised the broadsheets as much as it animated the tabloids.. Levy and O’Connell leap to Biggs’ defence in The Times of 28 March 1981.

Abduction of Mr Biggs

From Dr D. Sayer

Sir, When Korean dissidents are forcibly abducted from their Japanese exile, we condemn. When Colonel Gaddafi’s execution squads ply their trade on British soil, we protest. What then are we to make of the current capers in the Caribbean ?

Mr Biggs would appear to be the victim of a kidnap. The “operation” of Mr Miller and his “ex-SAS” colleagues is, in plainer language, a piece of violent and lawless thuggery which would not be tolerated anywhere the rule of law prevails. To seek Mr Biggs’s extradition from Barbados under present circumstances condones that thuggery and makes a mockery of that law. Having failed to secure Mr Biggs’s departure from Brazil by legal means, the British Government should leave him where he is.

Yours faithfully,

DEREK SAYER

University of Glasgow (Department of Sociology),

61 Southpark Avenue,

The University,

Glasgow

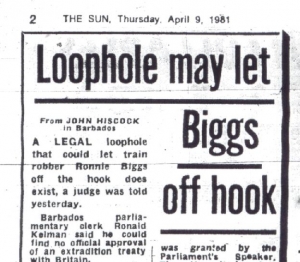

From Mr D. N. L. Levy and Mr K. J. O’Connell

Sir, It is important to correct an error in R. M. Francis’s letter (March 27) in which he claimed that the train driver in the Great Train Robbery died because of “. . . an assault during the carrying out of that crime.”

The robbery took place in August, 1963. The train driver, Mr Jack Mills, died of leukaemia six and a half years later at the age of 63. When he died the West Cheshire Coroner stated: “I am aware that Mr Mills sustained a head injury during the course of the train robbery in 1963. In my opinion thee is nothing to connect this incident with the cause of death.”

Yours faithfully,

DAVID N. L. LEVY,

104 Hamilton Terrace, NW8

KEVIN J. O’CONNELL,

84 Cholmley Gardens, NW6.

I was unsure as to what would be best. On the one hand I could do as Heim had asked, call Neufeld in New York and see if money might help to stave off what seemed to be inevitable. Or we could use the money to set up some sort of trust for Michael, rather than waste it on a hopeless task. (The thought of keeping the book money for ourselves never entered our thinking – Kevin and I both felt a strong affection and loyalty for Ron that far outweighed any idea of personal gain from his predicament.) One thing was clear, I did not want to take the decision without advice from someone who knew Ron very well and could make an objective judgement as to what Ron himself would want us to do under the circumstances. So I spoke to Ron’s wife, Charmian Brent, in Australia. Clearly Charmian would have a far better idea than I did about how Ron would want any available money to be used.

Charmian and I spoke at some length. She was still extremely loyal to Ron and very concerned about his predicament. We discussed Ron’s chances in the Barbados courts and the argument, being discussed by the media, that he should not be extradited because he had been brought to Barbados by kidnapping. Charmian explained to me that this line of reasoning was pretty hopeless because extradition law in the UK and hence in Barbados is based on the principle that it matters not how a person arrived in court – what matters is that he is there. I then put it to Charmian: we had some money which we could use to try to put up a legal defence, seemingly a hopeless exercise, or we could use the money for a trust fund for Michael. What should we do? Charmian was adamant. ‘I know Ron very, very well’ she said. ‘…and I can assure you that he would want everything possible to be done, no matter how hopeless it might seem, to get him out of there.’

So as soon as I had finished speaking to Charmian I called David Neufeld in New York. I explained the situation and he told me that he already knew about the case – Ron’s arrival in Barbados had been shown on American TV. I told Neufeld that he came highly recommended and I asked if he could do anything to help.

Neufeld explained that he was not allowed to practise law in Barbados but said that he was a member of a worldwide legal network that enabled him to find the best lawyers in any country for any particular aspect of law. If we wanted him to he would be willing to go to Barbados to try to put together a defence team. I asked him to consider what would be necessary and he promised to call me back soon, which he did. (This was in the evening, London time.) Neufeld had identified a flight leaving New York at noon the next day for Barbados. He would be willing to take that flight, try to find the best lawyers on the island to fight Ron’s case, and negotiate with them. Nothing more. Any legal fees on the island would be on top of his own fee and expenses. And since he did not know me from Adam, Neufeld wanted me to arrange to get him $6,000 before his ‘plane took off!

I asked David Neufeld who his bankers were – Manufacturers Hanover Trust. I looked them up in the London telephone directory and found they had an office at the edge of Grosvenor Square, about five minutes’ walk from where Kevin and I kept our company bank account. So I took down the details of David Neufeld’s own bank account and branch and told him that the following morning I would be at our bank when it opened, withdraw the $6,000 in cash, walk round to Manufacturers Hanover Trust, deposit the cash to the credit of his account and tell the bank manager at MHT to expect a call later that day, asking for confirmation that the money was there, deposited for the credit of David Neufeld. With the five-hour time difference between London and New York working in our favour I would have the money credited to Neufeld’s account before he even got out of bed. And so it came to pass. At midday Neufeld took off for Barbados.

Neufeld’s first call to me after his arrival on the island was confusing rather than encouraging. He explained, which I already knew from the TV news, that a Barbados lawyer or two had already offered to fight Ron’s case, assuming that lots of money must be available for this purpose. (It is amazing how many people I came across, even 18 years after the Great Train Robbery, who expected Ron still to have some of the loot.) Neufeld had spoken with them and with one or two other lawyers on the island and was trying to form a suitable team.

The next call from Neufeld was more upbeat. He had a team of three barristers willing to work on the case. The lead was Frederick (‘Sleepy’) Smith (latterly Sir Frederick), a former Attorney General of Barbados. I felt this was an excellent start. If a former Attorney General could not do something useful then no-one could. The other two lawyers Neufeld had put into the team were, he assured me, excellent advocates and very intelligent: Ezra Alleyne and Alair Shepherd. But they too wanted money – I forget now exactly how much but it was also in the region of $6,000. With a warning from Neufeld that this was going to be a very difficult case to defend, Kevin and I decided to continue. I promised to wire the money the next day and sent it to Sleepy Smith’s account at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce in Bridgetown.

That same evening I saw Smith on the TV news, coming out of court after a preliminary hearing, saying that the case was hopeless and Mr Biggs would be returning to England in due course to complete his 30-year sentence. Was this really what Kevin and I were spending all the book money for? I decided to take a closer look and booked myself a flight to Barbados, travelling via New York where I stayed overnight with David Neufeld. After what had seemed like an interminable period of negative news it was a great relief to be with someone else who was trying to help Ron.

Hey, we’re going to Barbados!

Shortly after I arrived in Barbados I met Sleepy Smith. He was an impressive man, quiet but with an air of experience about him. He arranged for me to visit Ron the following day in the island’s prison. Ron, quite naturally, was rather subdued. He asked about Michael and I reassured him that John and Lia were taking very good care of the boy. We discussed his chances in court which, Ron knew, lay somewhere between very slim and non-existent. And then he started to talk about what he wanted if he had to return to England. His one big wish, if it could be arranged, was that he should not be taken back in handcuffs.

The extradition hearing was before a magistrate. I had spent only a little time with the defence team, all three of them being too busy to do much more than explain to me a few simple details of procedure. But once having met them I felt satisfied that David Neufeld had done a good job. Each member of the team he had assembled seemed to have an excellent legal mind and to be very hard working.

I sat in the front row of the court extremely conscious of the presence of two Scotland Yard detectives, who I recognized from television news bulletins, sitting at the rear. They had been sent to Barbados to bring Ron back to the UK after the expected result but professed instead to be in Barbados on holiday and ‘visiting some old friends we knew at the police training centre in Hendon’. Also in court, waiting to see an old friend, was Ronnie Leslie, the man who built the furniture van platform and drove the van in which Biggs escaped from Wandsworth (sentence three-and-a-half years). I met Leslie a couple of times – a genuine friend who was proud of what he had done to help Biggs and not at all resentful of the time he did for it.

When the case opened there were formalities of identification. A burly detective, who had worked on the train robbery case in 1963, had come from London to state that the man in the dock was indeed Ronald Arthur Biggs (which Ron himself freely admitted). The detective also confirmed that Ronald Arthur Biggs had been convicted of conspiracy to rob the train and had been sentenced to 30 years in prison, but had escaped from Wandsworth only a year into his sentence.

‘I can’t tell you the details’ said Alleyne, ‘. . . but we think we’ve found something.’ He had spent the whole night in a library and had unearthed some amazing information.

After the identification formalities the case proper began. There were arguments based on the fact that Ron had been kidnapped but they did not seem to be getting anywhere. Eventually the case was adjourned until the next day and I left the court. As I was walking through the grounds of the court building a man whom I had noticed in court stopped his car and beckoned me. ‘Are you a friend of Mr Biggs?’ he asked. I told him I was and he then introduced himself – he was the British High Commissioner, the Queen’s representative in Barbados. ‘I must tell you what happened when I went back to the office at lunchtime’ he said. ‘Of course my staff all wanted to know what was going on in court and I told them that the morning’s events had been amazing, that Biggs had jumped out of an open window, into a waiting lorry and had escaped. When they heard this they all, every single one of them, cheered.’

The High Commissioner was delightful, especially in view of his role as the representative of the Crown. He asked if there was anything he could send to the prison to make Ron’s stay more comfortable, to which I suggested some books and magazines (which, I learned later, he did send). And he told me that if there were any other requests he would see what he could to fulfil them.

The next morning I arrived at Sleepy Smith’s office, to walk with him to court. Ezra Alleyne was there, very excited. ‘I can’t tell you the details’ said Alleyne,’ . . . but we think we’ve found something.’ It turned out that he had spent the whole night in a library and had unearthed some amazing information. I would have to wait until the hearing reopened to discover what it was.

While I was waiting in court for the case to resume, one of the Scotland Yard minders came over to me and introduced himself as Eddie Ellison. He was charming, polite and friendly. He asked if I was a friend, a journalist or a publisher and I told him. He then said that if he had to take Ron back to London was there anything he could do to make the trip more palatable for Ron? I told him about Ron’s request that handcuffs not be used but Ellison was somewhat non-committal about whether he could accede to this, though he did say that in return for Ron’s word that he would behave on the flight he and his colleague would make the journey as comfortable as they could for their charge. Then the burly detective appeared in front of me.

‘Are you a friend of this man Biggs?’ he asked. When I replied he puffed himself up to his full height and gave me a brief lecture on morals:

‘Do you realise’ [strong emphasis on the ‘r’ of ‘realise’] that this man robbed the Royal Mail?’ [very strong emphasis on the ‘R’ of ‘Royal’ and on the ‘M’ of ‘Mail’].

I said that I did know Ron had robbed the Royal Mail and that I felt 30 years was far too severe a punishment when murderers were often released from prison after 10 or 15 years. End of conversation.

The defence called as their main witness the Clerk of the Barbados parliament, who was asked to explain the procedure when a new act is introduced. The Clerk explained that the act must be laid before Parliament for a period of what is known as ‘negative resolution’ and that if there is any objection to the act from a Member of Parliament then there must be a debate. Alleyne then asked for how long the 1979 Extradition Act, the law under which Ron’s extradition was being sought, was laid before Parliament. And upon hearing the answer Alleyne asked the Clerk to confirm that the period was not sufficient under Barbados law to satisfy the conditions for a period of negative resolution. When the Clerk confirmed this to be true Alleyne asked boldly: ‘Then does this mean that the 1979 Barbados Extradition Act was not passed into law under the terms of our Constitution?’ The Clerk admitted that this was indeed the case – the 1979 Barbados Extradition Act was not law!

To understand the significance of this legal bombshell one must realise that previously, when Barbados was a British colony, the extradition act in force did not include Great Britain in the list of countries to which people could be extradited. This was because, for countries in the Empire, extradition was automatic. But when Barbados gained its independence that was no longer the case and so, in 1979, a new act was laid before the Barbados parliament (but not for long enough). And therefore, with the 1979 act invalid, the original extradition law still applied, but under that original law the UK was not on the list of countries to which extradition would be granted!! This formed the main argument for the defence.

The magistrate retired to consider his verdict and while he was out of the room Eddie Ellison wandered over to me. ‘I’m not sure that he will have the bottle to release your man today’ he said, ‘but I’ve seen a lot of appeals in my time and if this goes to appeal I don’t think we will be coming back for the hearing’. In other words, if he doesn’t get off now, he almost certainly will be freed on appeal.

Ellison was right. The magistrate did not have enough bottle. He found in favour of the prosecution and ordered Ron to be sent to the UK.

Somewhat dejected I returned to London. But, from what the defence team told us, very soon it became clear that the appeal was going to be successful – Ezra Alleyne’s argument was irrefutable. So the question arose, how could we get Ron back to Brazil? Every country that had commercial flights from Barbados had an extradition treaty with Britain. A boat would not be safe – the Royal Navy could step in if it wished and snatch Ron, while John Miller and his gang were still a worry. There was no alternative but to hire a private ‘plane to fly Ron back home.

David Neufeld investigated the cost and found a company that would provide a Learjet from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to fly to Barbados, pick us up, and fly on to Rio. I wanted to minimize the cost and asked for a price to Belem, which is considerably closer to Barbados. The quotation was $16,000 (US dollars, not Eastern Caribbean dollars). And of course, payment in advance please! Neufeld was concerned that if we paid all the money in advance the pilot might simply forget to arrive in Barbados. So he negotiated a deal whereby a friend of his, a Florida based lawyer, would get on the ‘plane in Fort Lauderdale and pay the cost of the return trip as far as Barbados. Then, when the Learjet arrived in Barbados, Neufeld’s friend would alight, we would board the ‘plane and I would pay the balance – the return fare from Barbados to Belem. This left us with only one minor problem – Kevin and I did not have $16,000, let alone the other expenses such as Neufeld’s own air fare from New York to Barbados and from Rio to New York, all the Belem-Rio tickets, and my own fare to Barbados and then back from Rio to London. What to do? Enter the media.

A week or so before the appeal was due to be heard I received a call from Desmond Hamill, an ITN journalist. He asked if he and a Brazilian colleague, working for O Globo, could come to visit us. We met them in Kevin’s flat where Hamill explained that they knew we had to hire a private ‘plane and could they please have seats on it. They wanted four seats: one for each of them and one for each of their cameramen. I knew that we would have only 3 spare seats on the Learjet so I proposed that they share a camerman. They agreed and we negotiated a price of $5,000 per seat – $15,000 in all. So at a stroke we had virtually covered the cost of the Learjet. But adding up all the figures Kevin and I concluded that we would be about £8,000 short. What does one do when one needs money? Go visit the bank manager!

Kevin and I had a manager who loved a liquid lunch. So whenever anyone who knew him wanted a pliant banker an appointment would be arranged for shortly after 3pm, when our man returned from lunch. Kevin and I were wise to this and duly made an afternoon appointment. We told the manager the whole saga and said that we wanted to borrow £8,000 to cover the shortfall in expenses. (By then we had decided to throw caution to the wind and do whatever was necessary to ensure Ron’s safe passage back to Brazil and Michael.) Our bank manager loved the story, said he could dine out on it for months, and agreed immediately to the £8K overdraft.

Barbados Again

David Neufeld and I arrived in Barbados for the appeal hearing with everything in place for a quick getaway from the island. (Kevin would have come with us but was on holiday with his family in the Bahamas.) The evening before the hearing, which was set for 23 and 24 April, we dined at an excellent restaurant with some of the defence team. The British media was on the island in force and I had talked to a couple of tabloids about an interview with Ron for a suitable fee (£20,000 was discussed), but nothing came of it and, frankly, I did not trust the newspapers concerned to come through with the money even if they had decided to go ahead. Various journalists asked if they could have an interview if the appeal was successful but our view was that we should wait in case a good offer for an exclusive turned up (which it didn’t). This refusal upset a few of the journos, the Daily Telegraph referring to me in a little act of pique as ‘the paymaster’.

Neufeld and I went into court on 23 April, with all necessary plans in place to leave the island in a hurry. The defence was appealing on 12 points of law, one of which was that the 1979 Barbados Extradition Act was not legally valid. There were three appeal judges, all very formal in wigs, just like the Old Bailey. One of the judges announced that they would first like to hear arguments on just two of the points of appeal, including the most important one, and then ‘if necessary we will hear the other points’. At that moment it was obvious to everyone in court that the outcome had already been decided.

The two points requested by the judges were put forward by the defence. The judges then decided to rise for an adjournment and after a few minutes they returned, announced that the 1979 Barbados Extradition Act was not law, found in favour of the defence and said that Ron was free to go. By an amazing stroke of fate John Miller and his gang had taken Ron to the only island in the whole of the Caribbean that lacked a valid extradition agreement with Britain!

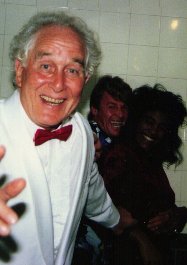

Immediately pandemonium broke out. David Neufeld and I ran from the building with Ron and ushered him into a taxi that we had planted opposite the court house. We drove to the house of the Brazilian Consul where Ron’s travel documents had to be prepared, prior to our departure that night for Belem. The moment we arrived at the Consul’s house David Neufeld got on the phone to Fort Lauderdale to order the Learjet to start its engines. His final words to the air charter company were: ‘And don’t you forget. That plane does not take off without the chicken sandwiches and the champagne.’

There was a party atmosphere at the Consul’s house all afternoon and evening. Lia Pickston called: ‘Is it true, David, what I saw on our TV? Is Ron really with you?’ She was delirious with excitement. Ron spoke to her and then she put Michael on the phone to his dad. Various other friends of Ron called. The media started to arrive in droves and we decided to allow a couple of brief TV interviews. While Ron was being interviewed by the BBC I happened to walk into camera holding a beer. My wife’s aunt, who knew nothing of my relationship with Ron, rang my home and asked my wife: ‘What is David doing there with that dreadful man?’ (Her husband worked at the Home Office, Prison Department!)

The flight from Fort Lauderdale to Barbados was not expected to be a long one but thunderstorms en route forced the pilot to land in Puerto Rico and wait for the storm to abate. The Barbados Prime Minister’s office telephoned us to ask if we could please take our man off the island ASAP as the delay was becoming an embarrassment. We explained that Ron’s travel documents needed to be prepared by the Consul – having no passport Ron needed a laissez passer – and that once the documents were ready Ron would be leaving immediately. By a huge coincidence, when we learned about the thunderstorm delay the Consul found that it was very much more time consuming to prepare the documents than he had originally believed. But, equally coincidentally, just at the moment when we learned that the Learjet had left Puerto Rico the Consul announced that he had finished his work and we could leave for the airport. One interesting thing we had learned during our sojourn that day – when the Barbados judiciary decided that Ron would be freed on appeal the Barbados Prime Minister had telephoned Margaret Thatcher to advise her as a matter of courtesy and to ask whether it would cause her any problems, to which she is said to have replied that ‘I don’t give a toss’.

Our taxi drove in the dark to the airport with Ron and I crouched down on the floor in the back, a large blanket covering us. David Neufeld got out of the taxi at the terminal building and the driver left the taxi in the car park as though it were empty. No-one came near the car until Neufeld returned to tell us that the Learjet had arrived and we could board. We met his friend, the one who had shepherded the ‘plane from Florida, and a very jolly drunk he was too. I wondered just how much of the champagne was left on board but I need not have feared – David Neufeld had ordered plenty and then some.

We met Desmond Hamill, the O Globo reporter and their cameraman on the tarmac. Money changed hands, from them to me and from me to the pilot. Ron peered into one of the jet engines and called out: ‘Are you there Mr Slipper?’ And then we boarded. I had never been in a Learjet before so I spent some of the flight having the navigator explain to me the controls and what was going on. Meanwhile Hamill and his O Globo colleague conducted their interviews.

The flight was a continuation of the party. The champagne flowed. The chicken sandwiches were excellent. And then there was the sunrise over the Amazon estuary, with Belem appearing in the distance. As we stepped onto Brazilian soil Ron knelt down and kissed the ground, Pope-style.

We were ushered into the VIP lounge at Belem airport to await the Cruzeiro flight to Rio. An airline official eventually remembered that we had to pay for our seats and relieved me of more of my fast dwindling wad of American Express travellers cheques. Soon we were on the plane to Rio and now it was the turn of a few Brazilian journalists who had learned of our flight plan and awaited us in Belem.

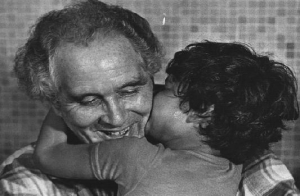

Ain’t Rio Grand!

Nothing could have prepared us for the reception Ron received upon our arrival in Rio. It was as though Ron was returning from a war in which, single-handed, he had saved the Brazilian nation. By the time we were through immigration David Neufeld and I were a few feet behind Ron who, by then, was completely surrounded by a mass of press and well-wishers. I saw John Pickston for a moment, who had brought Michael to the airport. As Ron raised his son aloft David Neufeld and I turned to each other and we both burst into tears.

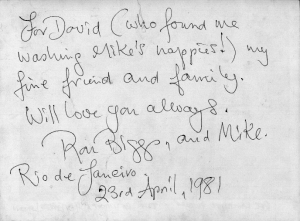

Ron gave me a photo of that moment, the reunion, taken by Reg Lancaster of the Daily Express. On the back he wrote: ‘For David (who found me washing Mike’s nappies!) my fine friend and family. Will love you always. Ron Biggs, and Mike. Rio de Janeiro 23rd April 1981.’

Ron gave me a photo of that moment, the reunion, taken by Reg Lancaster of the Daily Express. On the back he wrote: ‘For David (who found me washing Mike’s nappies!) my fine friend and family. Will love you always. Ron Biggs, and Mike. Rio de Janeiro 23rd April 1981.’

Postscript

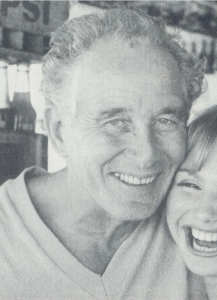

In January 1998 I was invited to Rio for a few days by a games company that knew I had originated the Mind Sports Olympiad and was interested in enlisting my help in promoting their game. While there I spent 3 days with Ron, who I had not seen for 17 years. We sat on the patio outside his hillside apartment, drinking beer and reminiscing. In the interim time had taken its toll – Ron’s long-time girlfriend Ulla had died of a heart attack and his good friend Armin Heim had been killed in a motorcycle accident.

Ron had not aged badly, but recently he had had an accident – walking in the dark into a chain suspended across a road. But he was the same Ron, the same raconteur, with a memory almost as sharp as it had been when

first knew him. He had been given permission to reside permanently in Rio and had no desire to leave. In fact he made the same joke then as he had done in 1978 and 1981 about the stories that occasionally appeared in the British press claiming that he yearned for London and its weather. ‘Why would I want to do that?’ he asked. ‘Just look at this view. Look at the weather here. Look at the girls on Ipanema beach. They must be mad if they think I want to walk down the Old Kent Road in the rain.’

Ron had always felt, however, that if he were to return to England the public mood would be so much on his side that the authorities would do a deal with him to allow him out after only a brief stay in prison. In this he was, sadly, completely wrong. I strongly suspect that when they convinced him to return to the arms of the law in England in 2001, The Sun encouraged him in this belief. It would have suited their purpose to do so.

Now (February 2002) Ron is a sick man. All attempts thus far to have him released have failed. In theory he still has 27 years of his sentence to run which, in practice, would probably mean about 10 years, if he were to live that long. He has had a few strokes but can still walk unaided. Michael and his legal team made strenuous efforts for him to be allowed to remain in Britain so that he could visit his father as frequently as is allowed, but the Home Office refused him permission and so, after all of Michael’s existing legal options had been eliminated, Ron married Raimunda on 10 July 2002, thereby making Michael legitimate. As the legitimate son of someone born in the UK Michael then had an automatic right to remain in the country whenever he pleases.

Unless he is released on compassionate grounds because of his failing health I do not expect to be able to see Ron again. My last memories of him are from 1998 – several beers on his veranda; lunch at the Copacabana Palace Hotel; a coffee at 2am opposite the café where ‘The Girl From Ipanema’ was written; and a visit to a night club where we heard one of Brazil’s leading singers, Gal Costa, with two-and-a-half hours’ worth of Brazilian love songs. These are some of the aspects of life in Rio that Ron loved.

Many people have asked me whether I feel any guilt about my association with Biggs and whether I regret helping a man who took part in the Great Train Robbery. No I don’t. Sure, Ron was a rogue in those days, but never a villain. He was a small-time criminal who got involved in the heist by introducing the robbers to a retired train driver whose job it was to move the engine of the mail train. But on that August night Ron’s driver was unable to do the business because the engine was a new type unfamiliar to him – he simply did not know how to drive it!

Many people believe, erroneously, that the driver of the mail train, Jack Mills, was killed during the robbery or as a direct result of it. False. Mills died seven years later of lymphatic leukaemia and pneumonia, and at Mills’ inquest the coroner stated that his death had no connection with the injuries he sustained during the robbery. Yes, the Great Train Robbery was a very serious crime, but 30 years was a ludicrous sentence. For murder in this country there is a mandatory sentence of ‘life’ in prison but many murderers get so much time off for good behaviour that they are out after as little as 10 years. Given that his sentence was grossly disproportionate to the offence he committed I have a great deal of sympathy for Ron’s decision to escape from Wandsworth. Since then he has not enjoyed a life of easy luxury as many people think. He suffered many very difficult years on the run; he had to leave Charmian and his three sons in Australia, where one of the boys was killed in a car crash; and for much of his time in Brazil he was constantly looking over his shoulder. I believe that Ronnie Biggs has paid, albeit in different ways, for his sins, and that he should be released. And if there were referendum on the subject I believe that the vote would be heavily in his favour.

Copyright © 2003 David N.L. Levy

Editor’s note

This article first appeared in Kingpin 36 (Spring 2003).

Ronald Biggs was released from prison on compassionate grounds on 6 August 2009, two days before his 80th birthday. He has spent most of the time since then in hospital and in a nursing home, appearing occasionally in public as he did for the funeral of Bruce Reynolds, the mastermind behind the train robbery.

Dear David,

What an interesting read and I agree with everything you say about Biggs. I was a journalist in Brazil during some of the Biggs years and have fond memories – an open character, gregarious, amusing, with loyal friends. It is indeed an appalling shame that establishment propaganda — so often repeated in the British press – kept him linked to Jack Mills’ injury when all the evidence says he had no responsibility, and as you say, the coroner found no link. He fitted into Rio so well it still surprises me that he returned to Britain. No doubt, as you say, he was given false assurances. All the best.