The Grandmaster

Magnus Carlsen and the Match that Made Chess Great Again

Brin-Jonathan Butler

224 pages | softback | £12.95

London: Simon & Schuster, 2018

Sarah Hurst

The directionless nature of Brin-Jonathan Butler’s book is evident from its title, ‘The Grandmaster: Magnus Carlsen and the Match that Made Chess Great Again’. Already there are two questionable concepts here: an attempt to weave in the theme of the election of Donald Trump, which took place just before the start of the World Championship match between Magnus Carlsen and Sergey Karjakin in November 2016, and the suggestion that the match made chess great again. If that doesn’t put you off, there is much to be enjoyed in this whirlwind tour of the (mainly American) chess scene – but more for those with a casual interest than serious players and chess history fans.

Butler is the author of books on Cuba and boxing, and his engaging style makes up for The Grandmaster’s lack of an entirely coherent narrative. Along with attending the Carlsen–Karjakin match and trying to understand what was going on in the minds of the two combatants, Butler also interviews chess luminaries from Fischer biographer Frank Brady to Judit Polgar.

While the stories of Bobby Fischer and Josh Waitzkin are very familiar, one of the most intriguing chapters in the book is about the promising chess player Peter Winston, an eccentric genius who disappeared in a New York blizzard in 1978 at the age of 20, shortly after losing all of his nine games in a tournament. At a school for gifted children the five-year-old Winston had impressed the headmaster by telling him what day of the week his birthday was on. Not long afterwards John F. Kennedy was assassinated and Winston delivered a eulogy in front of the school.

Winston turned his attention and intellectual brilliance to chess, but struggled with mental health and drug problems as a teenager. His chess career peaked when he tied for first place at the US Junior Championships in 1974. He qualified for the World Junior Championships in Manila, but could only manage sixth place. Butler searches in vain for any records that could shed light on Winston’s disappearance, but his sympathetic conversations with Winston’s friends briefly bring the lost boy back to life.

Like many writers before him Butler is fascinated with the link between chess and mental illness, and refers to the standard examples of Bobby Fischer, Paul Morphy and Wilhelm Steinitz. Certainly there are people who have had an abnormal obsession with chess, but chess can often also be the one stable anchor in a life of mental turmoil. The documentary Magnus gives clear indications that Carlsen is on the autism spectrum, and dedicating his life to a pursuit that required a phenomenal memory and analytical skills but no social interaction has been ideal for him. Other people on the spectrum sometimes sink into loneliness and frustration, unable to express themselves.

Butler continues the theme of chess as a refuge with his visit to the Chess Forum in Greenwich Village and meeting with its owner, Imad Khachan, who describes how he was dragged out of bed to open the shop on the morning of September 11, 2001, ‘by players literally covered in debris from the collapsed towers’. People had nowhere else to go. A former manager of the Village Chess Shop, Aaron Louis, tells Butler a similar story:

‘Everyone they knew, their family was there. The owners recognized that and they wouldn’t close. Some people who were evacuated from the towers went to the Chess Shop and just kept playing. Never left. It was the only way they could deal with the trauma. After the attacks, we stayed open for days and kept the lights on.’

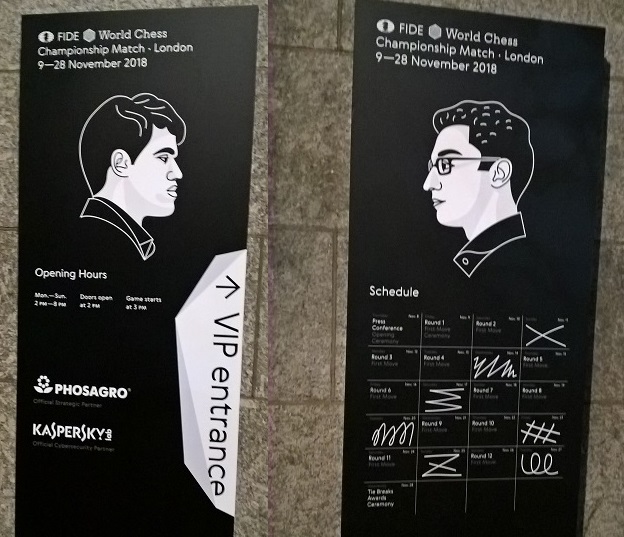

Khachan came to New York from war-torn Lebanon, but found he was in more danger from ex-convict, drug-dealing chess hustlers. He points out that chess addiction can be harmful, but at the same time adds that the Chess Forum is a community that brings together the rich and poor, and is something genuine, not full of hype. By contrast, Butler finds himself denied access to Carlsen and Karjakin at the match, which is a tasteless celebration of wealth sponsored by Russian fertilizer company PhosAgro, with Woody Harrelson making the ceremonial first move. Khachan also laments the direction chess has taken, telling Butler that Garry Kasparov asked for $30,000 for a 20-minute visit to the Chess Forum.

The topic of the Russian money and influence in chess is one that Butler might have explored more, especially since Karjakin has embraced his role as cheerleader for Putin’s annexation of his homeland, Crimea. But the match was not viewed as a Cold War 2.0 struggle, and it didn’t capture the public’s imagination. Nor did the recent Carlsen–Caruana match with its 12 draws. But there is still a flourishing chess culture all over the world that can always inspire more people, and that is what really makes chess great.

Gary Kenworthy

→ Commenting on: Tim Krabbé: 20 Questions

Jon Manley

→ Commenting on: No Regrets: Boris Spassky at 60

IchessU

→ Commenting on: No Regrets: Boris Spassky at 60

S.B. Cohen

→ Commenting on: Chess and Sex – The Survey