‘Hugh had been in London and at John Lewis’s for only about a year when we were overtaken by the war which changed all our lives. In September 1939 the British team for the International Team Tournament, consisting of Sir George Thomas, Alexander, Harry Golombek, myself, and B.H. Wood, were in Buenos Aires, where we had arrived (with the exception of Sir George) on an elderly Belgian boat called the Piriapolis, specially hired to transport a large number of the European teams. This was, as may be imagined, a remarkable menagerie of chess players, who in those days (long before the improvement in the status of chess as a profession) were much more Bohemian and less respectably bourgeois than they have since become. Hugh derived a great deal of amusement out of witnessing my reactions to this motley gathering.

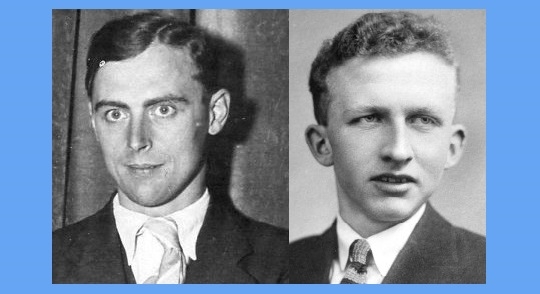

Hugh Alexander in 1939

When we reached the Argentine we had time only to complete the preliminaries, and to qualify successfully for the final, when the war which had been hanging over us for so long finally broke out. A decision had to be taken at once, and with the visions of London in flames most of us did not think we could go on playing chess. The British team, therefore, withdrew, and by the kindness of Sir George Thomas, who lent us the money. Hugh and I came back with him on the Alcantara, which happened to be leaving Buenos Aires that very night. As may be imagined it was a curious voyage. The ship was blacked out, and was carrying less than 100 passengers instead of her normal complement of 1500 or so. It was here that I first acquired, and encouraged Hugh to acquire, a taste for wine. We reckoned that if the ship were going to be sunk we might as well enjoy ourselves, and as I was then a bachelor expense was no serious object. From time to time, too, Sir George Thomas entertained us most hospitably in in his first-class cabin. We also took lessons in ballroom dancing. Hugh threw himself into this, as he did into everything he undertook, with the utmost enthusiasm, and proved far more proficient than I. The voyage passed without incident, except when waking from my watch-keeping on deck I mistook a porpoise for a submarine! We came safely home unconvoyed in something like thirteen days.

There ensued the strange autumn of the ‘phoney’ war, in which both of us were looking for something to do. After I had been turned down for military service I found myself invited early in the New Year by W.G. Welchman, a contemporary from Trinity who subsequently became a mathematical Fellow at Sidney Sussex, to go to Bletchley to join a mysterious organization then known as the Government Code and Cypher School. There I found Hugh, who had arrived, as far as I remember, a week or two earlier. It was to be our home until the end of the European war.

Much has been written lately about what came out of Bletchley, but only from the point of view of the user. Security restrictions on the story of the breaking of the Enigma from the technical point of view have not yet been lifted. I still hope that they may be in my time. It would, I believe, make an enthralling story which would be particularly fascinating to chess players. For both Hugh and myself it was rather like playing a tournament game (sometimes several games) every day for five and a half years.

Although by now we had been close friends for at least fifteen years, we became not only friends but colleagues in a game even more tense and much more important than chess.’

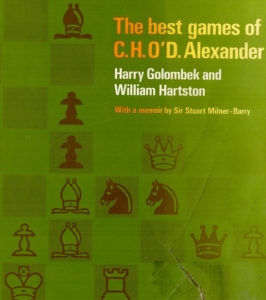

Sir Stuart Milner-Barry remembers Hugh Alexander

in Harry Golombek and William Hartston, The best games of C.H.O’D. Alexander (Oxford University Press, 1976), p.3.