H.E. Bird: A Chess Biography with 1,198 Games

Hans Renette

608 pages | hardback | 150 illustrations | 1,198 games | $75.00

Jefferson: McFarland, 2016

Adrian Harvey

During the period after 1860 three British chess players had a plausible claim to be in the world’s top five at various times: Blackburne, Gunsberg and Burn. All three had substantial results – the first’s victory in the Berlin tournament of 1881 making many regard him as the world’s leading tournament player. The subject of the book under review, Henry Edward Bird, was surely not in the same league as the other three and Renette’s declaration that some ‘considered him to be one of the world’s strongest masters (even though he fell just short of the absolute top)’ seems unlikely.1

It is difficult to assess Bird’s relative strength. While this reviewer considers that Renette substantially overestimates his quality, his assessment is more accurate than that of the otherwise astute chess historian Ken Whyld who put Bird on a par with George Gossip.2 This does Bird a great disservice, for he far outclassed Gossip, a minor master with a tournament record bristling with wooden spoons.3 The fact is that it is very hard to place Bird in the hierarchy of British chess players. Perhaps Tim Harding offers the best judgement of Bird, aligning him with a cluster of good players who were significantly below the game’s elite.4 In his long career Bird achieved some good results and was always a dangerous player, but he was too inconsistent to enjoy eminence. When evaluating Bird’s play it is worth noting two factors that might have prevented him from scaling greater heights. First, he was a very quick player, arguably the speed king of his era, and impulsive. Second, he suffered poor health, especially gout, which lowered his performance on many occasions, notably in 1873. In this light Bird’s chess career can be seen as that of an underachiever. It is likely that he would have accomplished far more had he shown less impatience at the board and enjoyed better health.

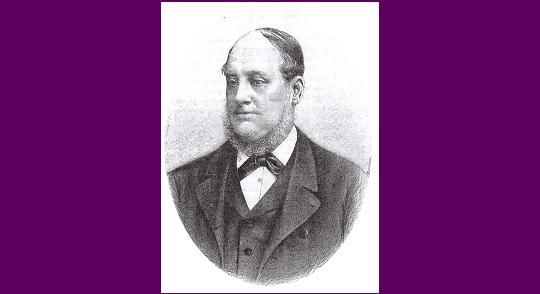

Bird was born in Portsea in 1829 and became an accountant like his father and older brother. From 1851 until 1872 accountancy was his main occupation, and chess his principal recreation. Bird had learned to play chess in 1844 (aged 15) and in 1846 began visiting Simpson’s Divan, forming a life-long friendship with another strong player, Boden. He was very active, playing numerous games against, among others, Charles Smith, Arthur Simons, George Medley and Edward Lowe. Occasionally he gave and received odds in what were effectively matches, but money never changed hands.5 At this stage Bird was a minor chess figure, for though he played in the 1849 tournament at the Divan and the London tournament of 1851, he made little impression in either.6 Bird spent the first half of his life mostly away from chess. Domestically, in 1855 he married Eliza Cain and settled in London.7 In 1857 he joined the Coleman, Turquard, Young Brothers Company as an accountant, rising steadily through the ranks. His work attracted some favourable mentions in the press, and it took him abroad.8 He first visited the United States on business in 1860, a time when civil war was brewing.9

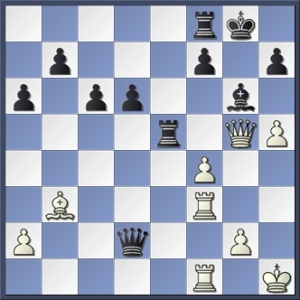

Bird – Horwitz

London 1851

position after 28…Re5

Initially Bird excelled at accountancy, notably in 1867 when his forensic skills uncovered fraud at the Atlantic and Great Western Railway.10 However, the good times did not last. He went into business with Edgar Lewis, a fellow accountant, and in 1870/71 they experienced trouble and were eventually declared bankrupt.11 As a bankrupt Bird was forbidden from practising as an accountant, so of necessity turned to chess for his living. Naturally Bird tried to conceal his bankruptcy from his chess friends, attributing his concentration on chess to a love of the game rather than professional difficulties. For many Victorian players, Blackburne for instance, chess was often a secondary occupation. From 1872 chess became far more important to Bird than to many other chess-playing professionals/semi-professionals, for it was his main occupation.

Temperamentally Bird was suited to earning a living from chess. In the first place, for him chess was principally a recreation, a delightful game to be enjoyed, and he might well have thought it foolish to risk large sums of money on it. At no stage in his very long career did Bird show any interest in playing chess for significant financial stakes. Given that he was an erratic player, this was a sensible approach. Bird seems to have been easy going, someone who really loved playing chess. He certainly did not regard chess as an occupation, and the commercial dimension of the game held little appeal for him. Even after circumstances had turned his erstwhile pastime into his livelihood, he was often content to take on all-comers, even for no stake. It was one of the reasons why many amateurs warmed to him and were moved to offer him their charity.

Other attributes endeared him to the public. Bird was an extremely quick player, his style was adventurous and aggressive, and bonhomie flowed from him.12 He was surely good company, eating and drinking during games.13 For these reasons Bird was ideally placed to earn a living from the game, albeit a meagre one. Bird would play for small stakes and give simultaneous displays. From 1873 he was very active and a regular attraction at the Divan.14

MacDonnell – Bird

London 1874

position after 17 Bg5

Although a convivial man, Bird was prone to disputes with other members of London’s chess-playing fraternity – probably inevitable in a city that drew players, native and foreign, to eke a living from the game. Several egos competing for slim pickings made for a combustible environment. The book examines many of these incidents, such as Bird’s quarrels with Steinitz and Gossip.15 Occasionally Bird would become involved in battles between the various clubs and organizations that administered chess, such as the one that divided the City of London and St George’s chess clubs, and the dispute between the Counties’ Chess Association and the British Chess Association.

“A Man Who Holds His Own with the Strongest Players of the World.

. . . Mr. Bird is a quiet, good-natured, gentlemanly looking person of forty-five: bald, short, portly, of round, florid face, fringed with light, soft whiskers. He might be mistaken for a sea captain on a merchant vessel. He moves the pieces gently, but without hesitation, and plays very rapidly. He is remarkable in the rapidity of his play. No English player of note equals him in this respect. He seems to have great endurance. Since his arrival here he has sometimes played ten or fifteen games, or even more, in a day. To be sure, they were not for a stake.”

‘The New Chess Lion’

New York Sun, 19 December 1875

[quoted in Renette, p.559]

Bird played chess as an amateur until bankruptcy in the early 1870s forced him to turn professional, when he was already in his forties.16 Much of his time was spent in London, but he undertook a great many tours around Britain, often to give simultaneous displays. His affability and lively, attacking chess made him a popular visitor. He also toured abroad. At that time it was quite common for British performers, such as Charles Dickens, to seek their fortune in America, and Bird duly followed in 1875.17 After a period of popularity he fell from favour with many people, especially the local press.18 It appears that he was often treated badly and even fraudulently, but his own ego might well have exacerbated these tensions.19 While in America from 1875 to 1877, Bird earned small sums playing offhand games and won small prizes in a few tournaments. His main focus was chess but he took on occasional legal duties too, working as compositor of deeds in Brooklyn in 1876.20

Bird – Mason

New York 1876

position after 30…Rf8

From the 1870s Bird was a busy tournament player and he proved his mettle in four of them: Vienna 1873, Paris 1878 – winning 700 francs = £2,309 (2015), Hereford 1885 – winning £20 = £1,948 (2015), and Manchester 1890 – winning £45 = £4,466 (2015).21 Bird was a strong player but several superior rivals were active in London at that time, notably Blackburne, Burn, Gunsberg, Lasker, Steinitz and Zukertort. These stars limited Bird’s access to prize money and the pressure they put on his purse culminated in a bitter pamphlet, ‘Farewell to Chess’, and a letter in the Glasgow Weekly Herald (25 December 1880) savaging professional chess players, especially foreigners.22 However out of character such outbursts seem for a man as genial as Bird, they demonstrate how precarious and turbulent the life of a professional/semi-professional chess player was during that period.23

While chess playing was the staple of Bird’s livelihood, he also had a minor literary career, writing books on a number of subjects, including chess. Like most of his chess-playing contemporaries, he conducted newspaper chess columns, largely in The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent but also, occasionally, in The Times.24 Bird was a casual writer. The game scores he quoted were often inaccurate, if kept at all, and he was as careless in recording facts about his own chess career.25 It seems likely that he earned some of his income illegally by continuing to work as an accountant despite being an undischarged bankrupt.26

Bird – Weiss

Vienna 1882

position after 20…Rad8

In 1899 Bird was diagnosed with an incurable illness and lived his final years confined to a wheelchair, dependent on others. It was fortunate that his chess friends regarded him highly enough to raise £425 for him. Indeed, by 1901 the funds they had accumulated secured him an annuity of £72.27 As if in sympathy with his decline, Simpson’s Divan, the centre of much of his chess activity, closed two years later. Bird died on 11 April 1908, leaving an estate of £35.28 This was hardly a fortune, but many of his contemporaries ended their days in far less comfortable circumstances. Gunsberg died bankrupt.

Bird’s standing quickly declined after his death, and for many years chess writers looked down on his eccentricity, recklessness and outmoded playing style.29 This thoroughly researched and readable book deploys a wide range of material to present a complete picture of Bird and goes a long way to restoring his reputation. This reviewer was especially impressed by the copious photos and illustrations that must have required a great deal of research. Renette presents the tables of all the tournaments in which Bird participated and these, along with the records of his matches, give the reader a more or less complete account of Bird’s entire chess life. If the author somewhat overestimates Bird’s stature as a player, with diligence and flair he has rescued this colourful master from the unjust neglect he has suffered.

Notes

- Hans Renette, H.E. Bird: A Chess Biography with 1,198 Games (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016), p.3. Renette presents a more measured assessment on p 17.

- BCM 121:5 (2001), p.263.

- Renette, pp.15-16.

- Tim Harding, Eminent Victorian Chess Players: Ten Biographies (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2012), p.122.

- Renette, pp.29-40.

- Renette, p.43.

- Renette, p.60.

- Renette, pp.64-5.

- Renette, p.65.

- Renette, pp.3, 6. Ironically enough, it seems that Bird lost a large sum of money because of this p.94.

- Renette, pp.91, 117. It was a black period for Bird. In 1868 his wife died aged 39, and his father died the year after.

- Bird’s play was characterised by tactical ingenuity and enterprise but he was vulnerable in endings, Renette, pp.11-12.

- Renette, p.9.

- Renette, p.119.

- Renette, pp.89, 105-6, 151-4.

- In 1871 Bird contested a match with Wisker for the title of amateur chess champion of Britain.

- Renette, p.179.

- Renette, p.6.

- Renette, pp.179, 196.

- Renette, p.220.

- The author would like to thank Gary Magee for converting the prize money to modern values.

- Renette, pp.267-9, 132, 560. Bird was no linguist. Tim Harding offers an alternative account of the Brunswick tournament in Joseph Henry Blackburne: A Chess Biography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2015), pp.267-8.

- The depressing life of the chess professional is vividly presented. Renette, pp.526-7.

- Renette, pp.288-9.

- Renette, pp.7-8.

- Renette, pp.118, 228. In reality it seems likely that he continued working as an accountant, though naturally covertly. In 1883 he became a discharged bankrupt, p.276.

- Renette, pp.527, 552.

- Renette, pp.552-3.

- Renette, p.15.

The following games are among several deeply analysed in the book to examine Bird’s distinctive style and his original contributions to opening theory. Bird’s games will be the subject of a future Kingpin article.