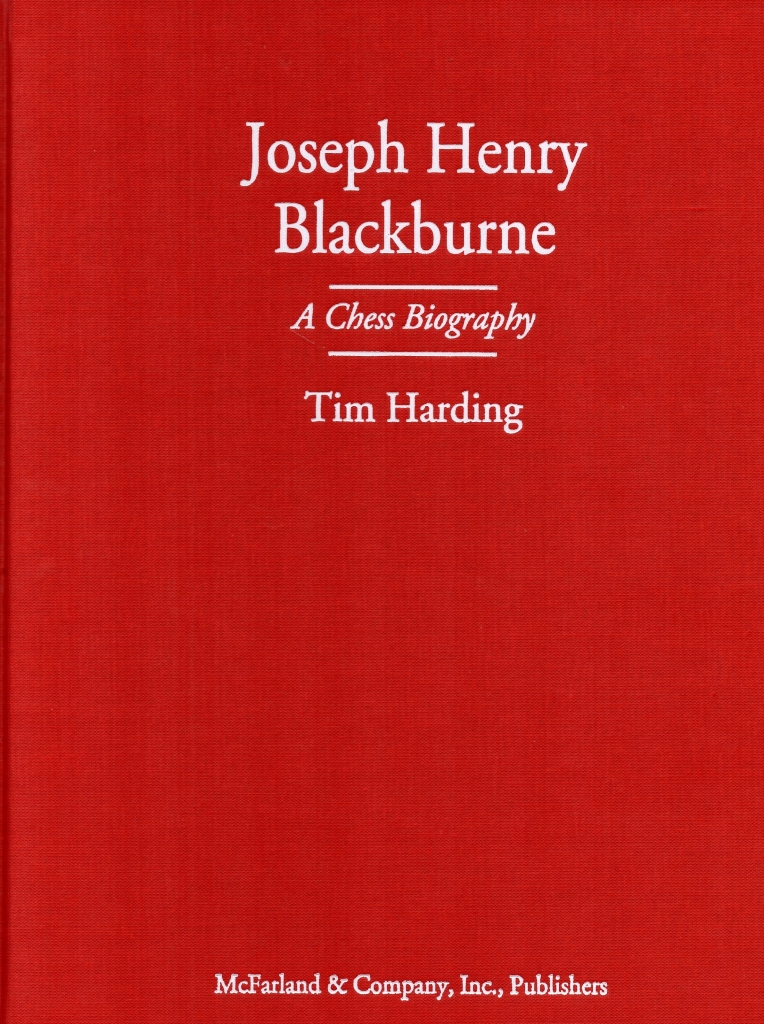

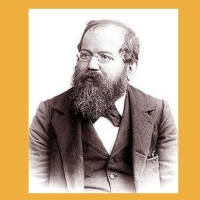

Joseph Henry Blackburne: A Chess Biography 1

Tim Harding

592 pages | hardback | 95 illustrations | 1,186 games | $75.00

Jefferson: McFarland, 2015

Adrian Harvey

When Nigel Short defeated Anatoly Karpov in their match in 1992 he surely secured the greatest triumph ever by a British chess player in an over-the-board contest.2 While Short had many successes as a professional, it is doubtful that his record excels that of J.H. Blackburne (1841–1924), a man whose chess-playing career lasted from 1862 to 1919 (indeed, he was even giving simultaneous displays in 1921 when he was aged 80!).3 In this excellent book the noted chess historian Tim Harding has consulted a wide variety of sources to produce a detailed, occasionally almost blow-by-blow, account of the career of Blackburne, surely the greatest chess player ever to hail from these shores.

Harding deserves credit for his diligence with sources, especially provincial newspapers, and he does well to delve into the records of Blackburne’s family members to compensate for his subject’s lack of private papers. Surely most vitally for chess players, Harding carefully assembles a detailed record of Blackburne’s numerous games, correcting errors through meticulous research.4 The result is a collection of Blackburne’s games the scope and accuracy of which is unlikely to be surpassed. It is a shame that there is no comprehensive list of tournament cross tables, for this would have been a fine resource.

‘A Little Bit of Morphy’

(Westminster Papers, 1876)

Blackburne’s father, Joseph, was a phrenologist who lectured widely on the subject.5 Perhaps he taught J.H. how to play chess. J.H. began by playing draughts but by 1862 had accumulated enough chess knowledge to play blindfold after witnessing Paulsen doing the same. At that time he had a tepid career as a semi-professional chess player and made the bulk of his income from other jobs, mostly clerical.6 He moved to London in 1865 and by 1867 was making most of his money from chess; but he continued his clerical work and it was not until 1871 that he can truly be classified as a professional chess player.

His chess income derived from four sources: public exhibitions; prize money from tournaments; prize money from matches; and fees and royalties from literary work.

The first of these provided his steadiest income from 1871 onwards, and Blackburne would tour the provinces annually thereafter. While this represented his bread and butter, he would make the occasional trip abroad too, making for what must have been a punishing schedule. If fulfilling engagements at so many venues was hard work, it was also very lucrative, and his trips to Holland (1874), Australia (1885) and USA (1889) were commercial successes.7

While he conducted many orthodox simultaneous displays, taking on large number of opponents, his real expertise was in blindfold play, a feat that pleased and amazed the public. These exhibitions proved to be enormously popular throughout his career, though age gradually diminished his powers, and younger rivals, notably Pillsbury, began to compete for the limelight.8 However, he remained active and as late as January 1912 won all four games in the final blindfold simultaneous display of his career.9

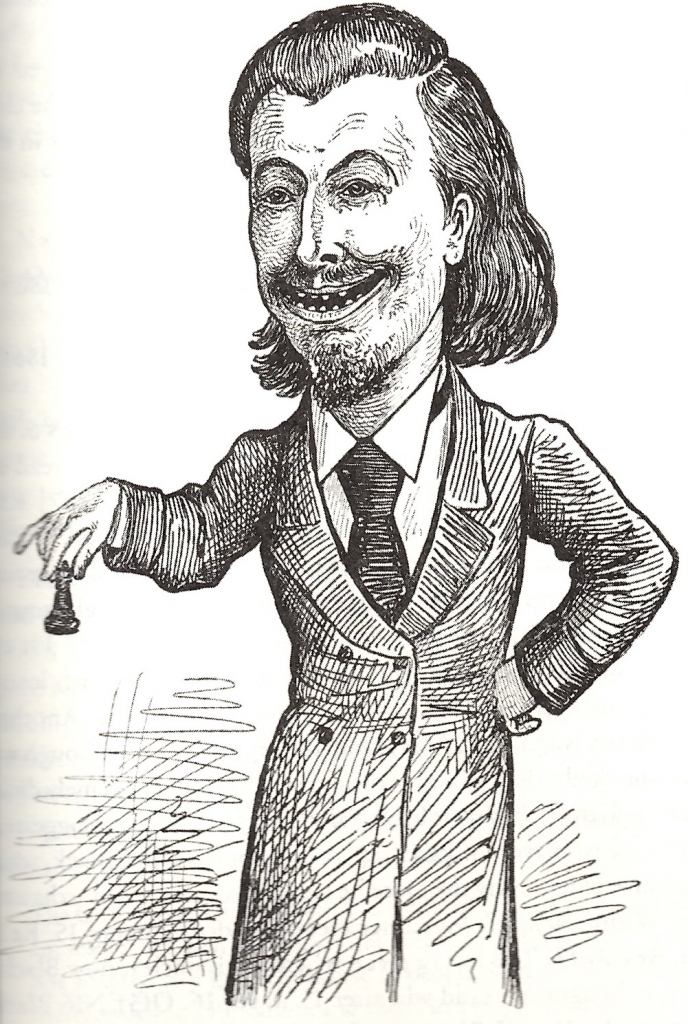

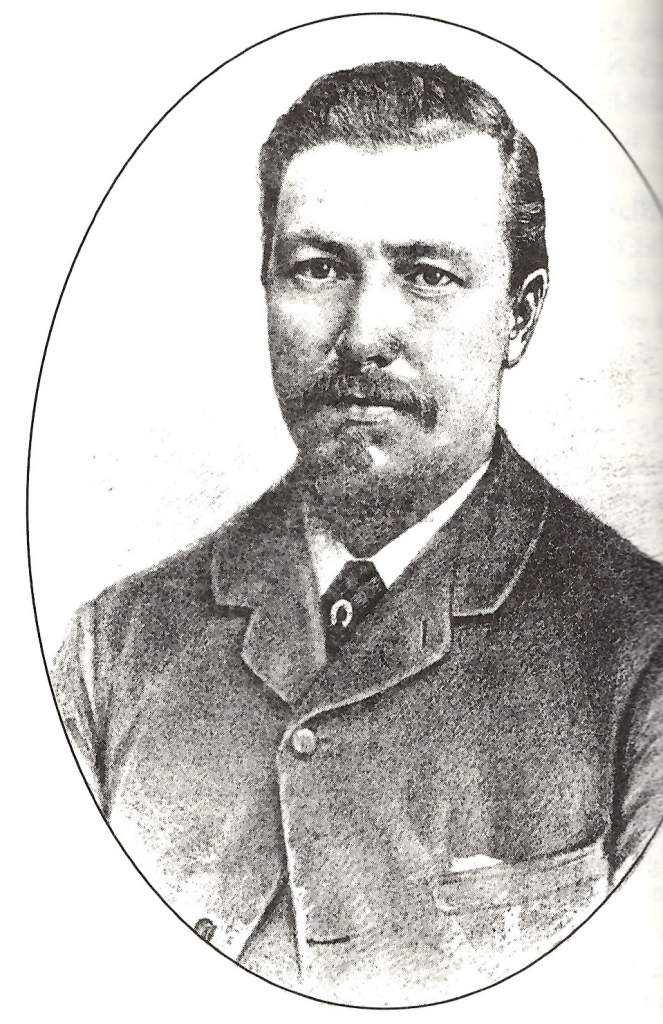

At the height of his fame, 1889.

Blackburne had his first significant competitive success winning the British Chess Association tournament of 1868/9. The following year he shared fourth place at Baden Baden and from then on almost invariably finished near the top of the tournament table at home and abroad. It should be remembered that at that time the staging of major chess tournaments was erratic, which limited his opportunities for prize money. Blackburne’s consistently high performance established him among the game’s elite. Influential commentators would sometimes refer to him as the world’s best active chess player, notably after he won the Berlin tournament of 1881.10

Blackburne’s brilliant, exciting play won him best game prizes, notably ten guineas for defeating World Champion Lasker in 1899.

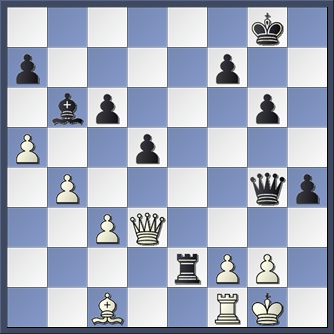

Lasker – Blackburne

London 1899

Black to play

From 1889 Blackburne’s standing in the chess world gradually declined and occasionally he had to depend on donations from a public appreciative of his past glory.11 Still, he continued to win minor prizes, such as 488 francs (the equivalent of £1,400 nowadays) at Ostend in 1905.12 Blackburne’s stamina declined with age, and the City of London Chess Club tournament in 1907 was his last event involving a dozen or more competitors.13 In 1914 he made his first ever visit to Russia, to compete in the St Petersburg tournament. Making light of his 72 years he drew with Alekhine, Bernstein and Rubinstein and defeated Nimzowitsch and Gunsberg, his play drawing much praise.14

Blackburne was regarded as a far stronger tournament than match player. With the exception of his victory over Zukertort, he suffered a number of heavy defeats in matches.15 There was never a suggestion that he might be a contender for the world crown, and his match earnings could never compare with those from performing exhibitions or competing in tournaments.

Blackburne differed from many other British chess masters of the time, notably Staunton and Gunsburg, in devoting little energy to producing chess literature. He composed chess problems which are scattered throughout several periodicals, but he did little chess journalism.16 In the 1860s he contributed to The Household Chess Magazine and from 1874 to 1875 to Potter’s City of London Chess Magazine, but these publications had small circulations. It is likely that his reports of the Vienna tournament of 1882 published in the periodical Land and Water were the nearest his chess work ever came to finding a broad audience. In 1899 he collaborated on a book of his best games but it disappointed many who felt that it could have been substantially improved.17

What sort of person was Blackburne? Harding often refers to his weakness for alcohol, as he did in an earlier book in which he stated that ‘Blackburne overcame these difficult patches and always returned to form’.18

Perhaps so, but we can say with certainty that alcohol fuelled at least one violent episode, involving Steinitz in Paris in 1878.19 Steinitz provides an extremely detailed account which, to this reader at least, is credible. Steinitz also mentions other fierce assaults that marked Blackburne’s career. Two of the victims were members of London’s chess community, and there was also a well-documented fight on a voyage to Australia in 1885.20 The latter led to a court appearance where Blackburne was found guilty. Although in this case Blackburne was provoked to violence, even Harding concedes that he behaved badly. Harding doubts the veracity of other accounts of aggression and even goes as far as to suggest that Steinitz might have started the fight!21 This reviewer is less convinced of Blackburne’s innocence. While it is very hard to substantiate such claims, it should be noted that at no stage did Blackburne or anyone, including Hoffer (who edited a number of chess columns and was a confirmed enemy of Steinitz), deny them. A statement in a contemporary chess journal may provide an elliptical reference to Blackburne’s penchant for bad behaviour:

‘his manners and bearing alike witness that he has never long sojourned in a place exempt from public haunt’.22

It would appear that Blackburne was fond of a drink and occasionally prone to violent behaviour. Generally, however, he was well regarded and his popularity inspired a number of public collections on his behalf, such as the gift of £400 raised in 1900.23

Blackburne seems to have suffered some pain in his personal life. He was married three times, in 1865, 1876 and 1880. All his wives predeceased him, though his final marriage lasted for ‘almost the rest of his life’.24 He had a rather complex domestic life, involving children and step children. Although he was not able to leave his relatives a large inheritance, Blackburne was solvent and bequeathed about £16,000 in today’s money. In this he far surpassed many of his contemporaries, notably Gunsberg, who died bankrupt.25

This is an excellent book, packed with game scores (often annotated) and engravings. The paper is of very high quality and the chess community should be grateful to both publisher and author for providing such a text.

Blackburne was a great chess player and this book is a fitting memorial to him.

Blackburne – Mortimer

London 1883

White to play

Blackburne – Steinitz

London 1883

White to play

Bird – Blackburne

London 1886

Black to play

Steinitz – Blackburne

London 1899

Black to play

Mason – Blackburne

Monte Carlo 1901

Black to play

Notes

- Tim Harding, Joseph Henry Blackburne: A Chess Biography (McFarland & Co., 2015). A number of corrections to the text can be found at Chessmail.com

- Blackburne won a match against Zukertort, a player who for many years was regarded as second only to Steinitz, but it took place in 1887 when Zukertort was a sick man and long past his best.

- Harding Joseph Henry Blackburne, p.500.

- The author gave the score of Blackburne’s win against Pindar in British Chess Magazine, Vol.107 (1987), p.75. Unfortunately a printer’s error introduced a mistake and the correct score can be found in Harding, Blackburne, p.45.

- Blackburne’s father used the prestige of his son’s famous victory in Berlin in 1881 to promote the virtues of his phrenological training. Harding, Blackburne, p.176.

- It is likely that as early as 1862 Blackburne was using chess to supplement income dwindling as a result of the Northern blockade of Confederate ports in the early years of the American Civil War which had impeded the supply of cotton to Manchester’s factories.

- Harding, Blackburne, pp.214, 286.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.390.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.483.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.167.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.353. At Hastings in 1895 he received a consolation prize of £10 10s.; a purse of gold for being in the British Championship in 1906 (p.353); and a prize in the 1911 event (p.480).

- Harding, Blackburne, p.441. I would like to thank Professor Gary Magee for calculating the value of the Belgium franc for me.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.454.

- Harding Blackburne, pp.489-93. Blackburne was given a special prize of 50 roubles (£417 in 2014 value). The author would like to thank Professor Gary Magee for calculating the value of the rouble.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.509 provides a detailed list of Blackburne’s record in matches.

- Harding, Blackburne, pp.513-19 contains some of his compositions.

- Harding, Blackburne, pp.404-5

- Tim Harding, Eminent Victorian Chess Players: Ten biographies (McFarland & Co., 2012), p. 229.

- International Chess Magazine, Vol.V (1889), pp.332-3.

- Harding, Blackburne, pp.133, 546. On p.216 Harding accepts that Blackburne was involved in a violent altercation on board a ship.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.284. This seems highly unlikely given that Blackburne was a burly man over six feet tall, while Steinitz was barely five foot six.

- Westminster Papers, Vol.VIII (1875/6), p.233.

- Harding, Blackburne, pp.213, 409.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.156.

- Harding, Blackburne, p.504.