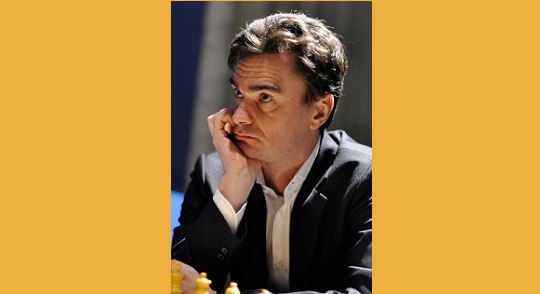

In a wide-ranging interview in 2003 Loek Van Wely talked to Dutch journalist Renzo Verwer about his life. This excerpt reveals much about the pressures of playing chess at the highest level and the gamesmanship of leading players.

‘. . . Man, in those top events when they smell blood and you are the wounded dog, they’ll go for your throat. Just look at what happened to Timman last year in the Corus event, and to me the year before . . . That’s how I got toughened up. I once got just 1½ points from 9 games. And in the Hoogovens (Corus) group B 2½ from 11. Your ego, your self-confidence is shattered.’

‘Normally I don’t think much about chess in my leisure time. I’m glad that I can separate the two. But if something bothers me, then I do brood on it. When I had a bad run in 2002, I hated it. I do get worried. If things turn against me, I think that the end of the world is at hand. That’s how I make my life complicated. For instance, after drawing with van der Wiel, I’m depressed and think “How is that possible? How terrible!” You have to be as objective as possible about your results, but quite often I think to myself “what a patzer!” or “what an idiot I’ve been, how stupid that I didn’t win”. You’ve got to be able to handle those negative emotions. And those top guys are trying to take advantage of that. I indicated in an interview with the Volkskrant last year that Anand pulls all kinds of dirty tricks to throw you off balance. He makes clicking sounds with his pen when it’s your move, and strange sounds with his throat and so on.’

Does he do that also to other players?

‘He does try to, I believe. But that’s hard for me to judge. Anyway you shouldn’t allow yourself to be influenced by it.’

But are you influenced by it? I mean, does it have a negative influence on your game or a positive one instead?

‘Unfortunately negative. It especially has an effect if you are under pressure or in a bad position, and that frequently happens against Anand. And when he starts with those tricks again, then it really gets to me. You got to understand, those guys are not naïve. They keep on learning. Anand probably learned a lot from Kasparov.’

Who slammed doors during their World Championship match?

‘Yes, among other things. When I play Kasparov, he is extremely correct. But when he knows that you are uncertain of yourself, he will make use of that knowledge. If you are unsure of yourself, you start looking at your opponent to get clues from his facial expression. Alternatively you look down on your opponent with a sense of superiority: “what a patzer you are!”’

‘Well, when Kasparov notices that you are unsure of yourself, he will start to act. And he is quite good at it. Garry is a great loss to the theatre!’

When Karpov blundered that exchange in a World Championship match, it looked as if Kasparov could not hide his surprise. Was he genuinely surprised?

‘No. What he does, is that he’s playing with the future in mind. Just winning is not enough any more – he wants to rub the blunder in as much as possible. He will see to it that Karpov feels like shit. That will have its effect in their next game. I don’t believe in the innocence of top chess players – they keep on learning.’

‘You don’t have to be an absolute asshole to get to the top, but it doesn’t hurt to be a bit tricky.’

You cannot afford to be naïve, you’ve got to realise that you are out in the big, bad world where everyone is trying to screw you. You’ve got to be suspicious. Don’t show them the whites of your eyes, and act like a snake. Alternatively . . . if you can play awesomely like Kasparov, it does not really matter. But he too has his tricks.’

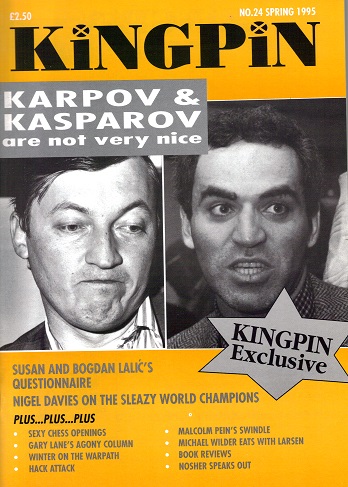

‘neither Karpov nor Kasparov can honestly claim to be great role models’

Nigel Davies in Kingpin 24 (Spring 1995).

I understand that you have to win the game by more than 1-0. Two years ago in the tiebreak of the Dutch Championship you were determined to crush Van den Doel 3–0, because ‘something like that will have its effect later on’. And you were in a position to win a game against Krasenkow quickly, but you decided to strangle him for another ten moves – because ‘that counts in later games’.

‘In principle, Renzo, that kind of game is ALWAYS being played. Even when players meet each other socially. During seemingly innocent tea-parties a few blows are struck here and there.

You must ALWAYS be on your guard. However much you work together, they are always harassing you. I had that experience with Topalov and his manager Danailov. In principle they should be your friends, but they try to pick your brains about what you think about certain variations – all of it under the pretence of friendship. Another example: they will come and stand next to me. Danailov does the dirty work: ‘Hey, why did you lose to that guy, how could you do that?’ Or: “You should have asked for more money to play in that tournament!” They try to do their best to make you feel bad. But that is how it is in every sport. What do you think the wicket-keeper is constantly saying to the batsman? That he can’t hit a single decent ball, of course!’

You just can’t get there solely by thinking up brilliant moves.

‘There are people who say “you’ve just got to make good moves”, but that’s nonsense. At the board one always suffers from negative emotions coming from the outside. As a top chess player, you’ve got to make use of them: in principle you are not good enough – maybe not even Kasparov is – to make that much of a difference only over the board. Controlled emotions can be a strong weapon, just like being a controlled deranged person. I got wise through trial and error. I wished I had known this ten years ago! And also how you have to work professionally as a chess player to be successful. If I had known all of that, it would have been a different story . . .’

First published in Kingpin 37 (Winter 2003/2004)

See also We Need to Talk about Gary, Part 2