Jimmy Adams

A continuation of my ‘Right to Reply’ to Edward Winter’s comments on my new book Gyula Breyer: The Chess Revolutionary.

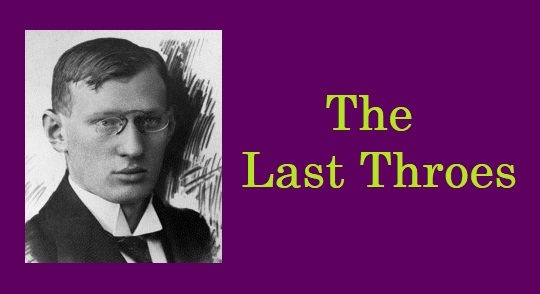

- ‘White’s game is in the last throes’

Pages 694-696 deal with this matter, superficially, making no mention of Breyer and the Last Throes.

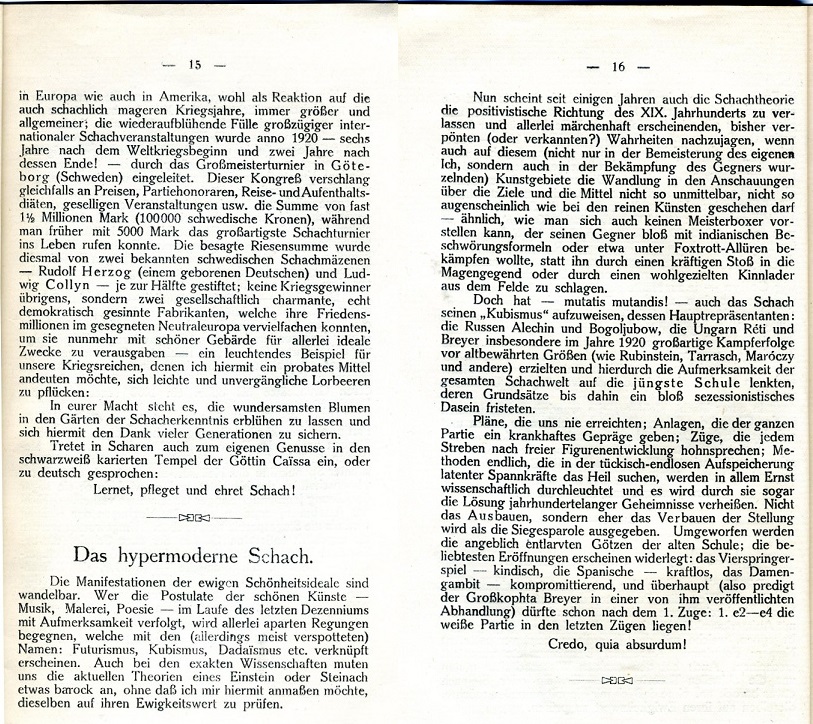

I did not use any material from this particular ‘feature article’ on chesshistory.com and so made no mention of it by way of acknowledgement. Already, in 1980, I had read the original source of the quote ‘After 1 e4 White’s game is in the last throes’ in Am Baum der Schacherkenntnis: Aufsätze und Plaudereien [The Tree of Chess Knowledge: Essays and Chit Chat].

This was a collection of contemporary German, Czech and Austrian newspaper and magazine articles, written by Dr S.G. Tartakower, to make up a 30-page booklet. By the way, in another ‘feature article’ that Ed. Winter wrote on ‘Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms’, he fails to mention that this booklet provides the first example of the label ‘Hypermodern Chess’ – apart from one instance he does cite from 1913, which, however, does not relate to the ‘real’ Hypermodern revolution.

I remember the year 1980 because it was when Freddy Reilly died suddenly from heart trouble and his father, Brian, by now nearly 80, promptly retired after thirty years of running the business of the British Chess Magazine. For the previous decade, Freddy had effectively carried out all the editing and production work on the magazine and, being technically minded, he was even able to develop his own pioneering photo-typesetting system, which enabled him to produce camera ready copy for the printer, complete with chess diagrams and figurine notation – something that in the pre-ChessBase days had presented real problems for publishers.

Brian was absolutely devastated.

He said to me: ‘I have not only lost my wife but now my son – as well as my friend and business partner.’

He even contemplated suicide, despite being the most sober and sensible of men. He asked me to come over to give him some help with the magazine and this was the start of regular Sunday morning visits to his home in West Norwood – now better known for being the area of South London where singer/songwriter Adele grew up and to which she dedicated her smash hit ‘Hometown Glory’.

He even contemplated suicide, despite being the most sober and sensible of men. He asked me to come over to give him some help with the magazine and this was the start of regular Sunday morning visits to his home in West Norwood – now better known for being the area of South London where singer/songwriter Adele grew up and to which she dedicated her smash hit ‘Hometown Glory’.

Shortly afterwards, the British Chess Federation came to the rescue, taking over the company and moving the production of the magazine to its offices in St. Leonards-on-Sea, where the retail division of the BCM had already been relocated from West Norwood in 1965. Here Bernard Cafferty did a great job in running the whole business, until he too retired after ten years’ work – and without taking a single day’s holiday throughout the whole period!

While visiting Brian, he gave me full access to his chess library, which had a strong historical bias, since much of it belonged previously to J.H. Blake, who in his best days was a very strong English amateur player. He lived to about ninety and was also the BCM’s games editor for a great many years.

It was in this wonderful collection that I saw for the first time such treasures as a complete run of the BCM, Kagan’s Schachnachrichten, La Stratégie, Revue d’Échecs, Chess Monthly (by Zukertort and Hoffer), L’Échiquier, Wiener Schachzeitung, as well as volumes of the US picture magazine Chess Review – and among the large number of books, The Tree of Chess Knowledge.

At Brian’s house I also met the fine writer and regular BCM contributor of historical articles, R.N. Coles, whose splendid book Dynamic Chess had introduced me to the life and games of Gyula Breyer when I borrowed it from my local library as an eleven year old.

Even then I recognized Breyer as a player of a chess style like no other. It seemed to me as if he had come from another planet!

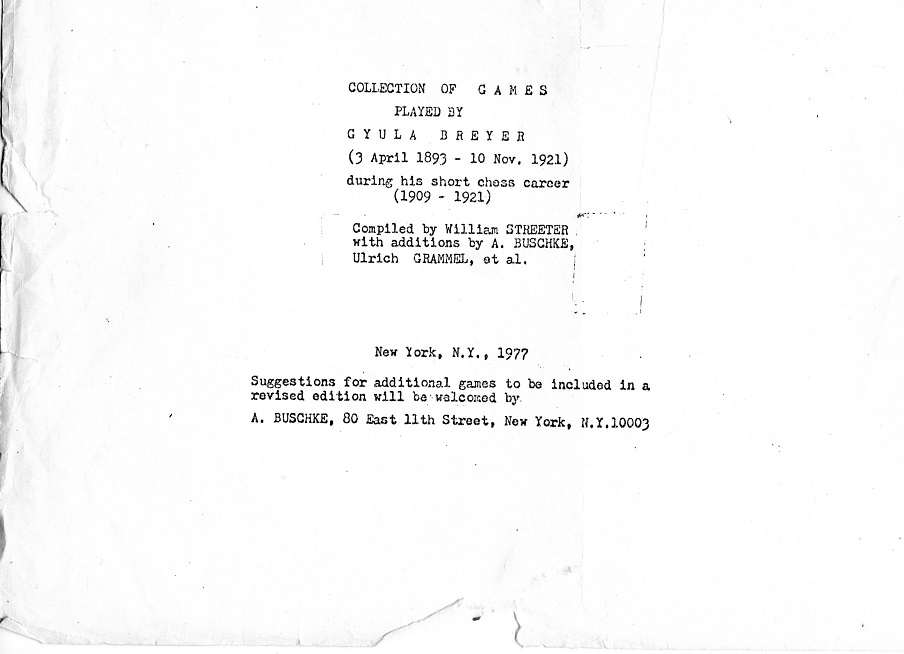

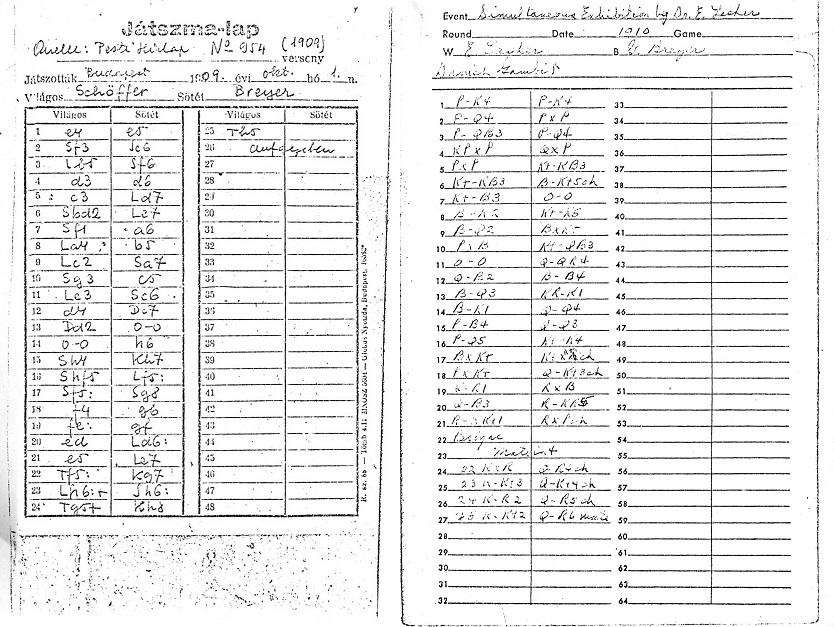

Yet, for next twenty years or so, I could count the number of Breyer games I had ever seen on the fingers of one hand, and it was not until a little later, when much to my surprise I saw a publication entitled Collection of Games played by Gyula Breyer advertised for sale by Scottish book dealer George Campbell, that my knowledge of the chess revolutionary dramatically increased.

Of course, I didn’t think twice and immediately sent off for the item, which turned out to be a photocopied collection of unbound score sheets on which were recorded about 200 Breyer games in various styles of both notation and handwriting.

I saw from the title page that it was published in New York, 1977, by Albrecht Buschke, who had for many years run an antiquarian chess bookshop in Manhattan, one of his regular customers being that avid reader of chess literature, the young Bobby Fischer.

From this moment on I was determined to write a proper book on Gyula Breyer and Bushke’s very informative work of research, in conjunction with William Streeter and Ulrich Grammel, had given me a flying start. This was followed by György Négyesi, author of an English edition of Lilienthal’s chess career, providing me with a great many articles by Breyer from Magyar Sakkvilág and Bécsi Magyar Újság. Looking back, it is truly amazing that from being aware of so few Breyer games for so many years, I ended up producing such a giant-size chess biography.

In fact, seeing Brian’s library, a veritable chess researcher’s paradise, inspired me to produce quite a few other books too in the 1980s, primarily to celebrate players and tournaments that had not previously been so documented in English chess literature.

Returning to The Tree of Chess Knowledge, this came out over the summer of 1921, while Breyer was still alive and, at least to my knowledge, the chess revolutionary never publicly objected to being credited with the proclamation ‘After 1 e4 White’s game is in the last throes’. However, by September 1921 he was too ill even to write his weekly column in Bécsi Magyar Újság and so he may not have seen the booklet or the periodical in which the article first appeared, let alone been able to respond to it.

I don’t know why Ed. Winter says I deal with ‘the last throes’ matter ‘superficially’ when the reverse is the case. After all, my book includes a translation of the full text of Tartakower’s related article, whereas chesshistory.com only gives a fragment and a few lines of translation from German to English.

Moreover Ed. Winter’s translation is off the mark and actually changes the meaning of what Tartakower originally wrote.

So here is an annotated version, giving some corrections.

‘The apparently [the German word ‘angeblich’ means ‘allegedly’ not ‘apparently’] unmasked idols of the old school are overturned; the favourite openings appear to be refuted: the Four Knights’ Game, childish, the Ruy Lopez, ineffectual [a closer translation of the German word ‘kraftlos’ is ‘powerless’ or ‘impotent’]; the Queen’s Gambit, compromising; and in any case (thus preaches the Grand Coptha [High Priest!] Breyer in a treatise published by him) White would be in the last throes already after the first move! [As given in the book, the correct translation from the German is ‘one of his published treatises’, the more so that in this case Breyer was not the publisher, only the writer. Also the text following the bracket should read ‘White’s game may be…’, as the German word ‘dürften’, which he translates as ‘would’, actually means ‘may’, expressing conjecture, and he also omits the word ‘partie’, which means ‘game’]

Credo, quia absurdum!’ [Again, this Latin phrase will be discussed later]

So, to repeat, Tartakower actually wrote ‘. . .after 1 e4 White’s game may already be in the last throes.’

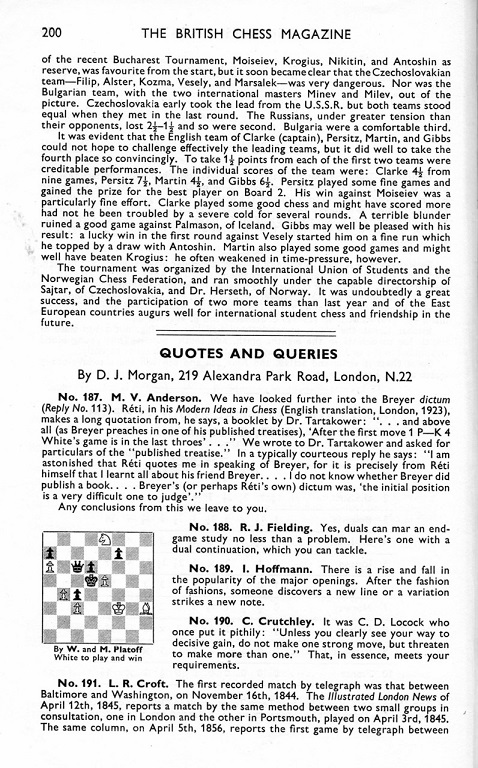

In the ‘Quotes and Queries’ column of the June 1954 issue of British Chess Magazine a letter, triggered by an Australian correspondent, M.V. Anderson, was published in which Tartakower somewhat distanced himself from ‘the last throes’ comment, even though he himself had quoted it, by writing:

‘I am astonished that Réti quotes me in speaking of Breyer, for it is precisely from Réti himself that I learnt all about his friend Breyer . . . I do not know whether Breyer did publish a book . . . Breyer’s (or perhaps Réti’s own) dictum was ‘the initial position is a very difficult one to judge’.

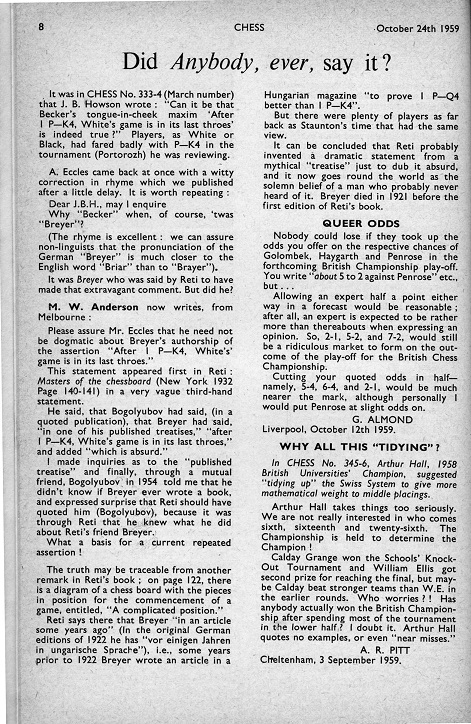

Further correspondence from Mr Anderson appeared in Chess in 1959, but it was seriously muddled, confusing Bogoljubow with Réti and Masters of the Chessboard with Modern Ideas in Chess. Fortunately, Mr Eccles straightened things out with a prompt response.

At first, Tartakower’s letter seemed rather strange to me since he knew Breyer well, having played in a number of tournaments with him. But then again, perhaps, despite being multilingual, he did not know Hungarian and so had never read Breyer’s original articles, since they were never translated into other languages.

Also in my book are quite a few pages where 1 e4 is discussed by Breyer, including his article entitled ‘A complicated position’ in which he gives a diagram of the starting position and analyses it in depth as if it were a middlegame. Indeed Breyer even states that all opening theory is nothing more than an analysis of this same starting position.

When it comes to acknowledging these crucial articles, Ed. Winter just refers the reader without further comment to Iván Bottlik’s German language book on Breyer, instead of analysing the material himself in English. So ‘the reader is no further forward’ as he does not even give facsimiles of the relevant pages on which these articles appear.

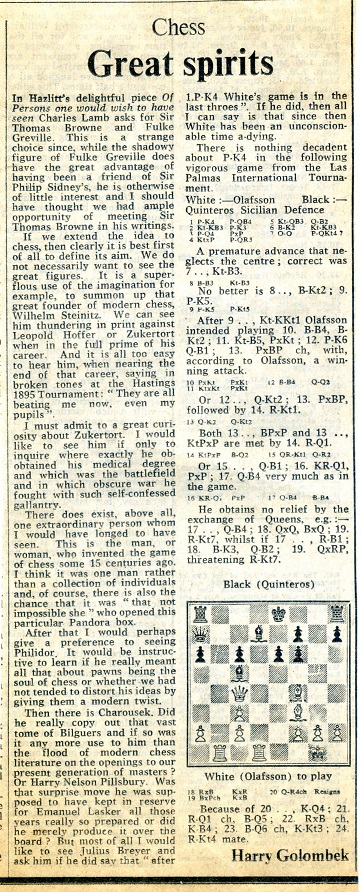

Then again, despite his interest in Golombek’s writings in The Times, in his ‘feature article’ on ‘the last throes’ Ed. Winter does not quote from the very nice column ‘Great Spirits’ in which Harry names players of the distant past he would like to meet and question on particular chess matters.

He climaxes with ‘But most of all I would like to see Julius Breyer and ask him if he did say that ‘after 1 P-K4 White’s game is in the last throes.’ If he did then all I can say is that since then White has been an unconscionable time a-dying. There is nothing decadent about 1 P-K4 in the following vigorous game. . .’ And he then gives a brilliant 20 move win by Fridrik Olafsson against Miguel Quinteros from Las Palmas 1974 By the way, in case you were wondering, ‘Julius’ is the English form of ‘Gyula’ and was the version also used by Réti in his Modern Ideas in Chess.

* * * * *

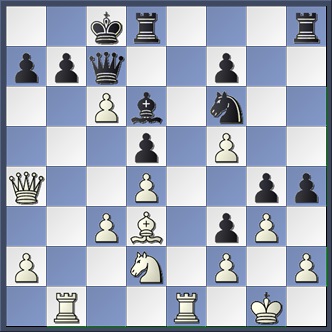

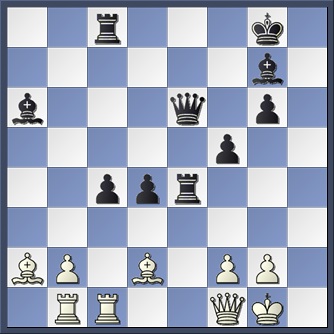

Here is a game from my book to show the sharp way Breyer tackled 1 e4 in practice. He was fond of storing up energy by playing a restrained opening, then later releasing that energy against some particular target. This strategy is effectively a forerunner of the so-called ‘Hedgehog’ system we see in …a6/…b6/…d6…/e6 Sicilians and Queen’s Indians. Breyer was so ahead of his time!

Kornél Havasi – Gyula Breyer

Five Masters Tournament, Budapest, June-July 1917

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nd7 4 Bc4 5 0-0 Be7 6 Nc3 Qc7 7 Be3 h6 8 Nd2 g5 9 Ne2 Nf8 10 Ng3 Ng6 11 Nf5 d5

12 Bd3 Bxf5 13 exf5 Nf4 14 Bxf4 exf4 15 Re1 0-0-0 16 c3 Nf6 17 b4 g4 18 Rb1 Bd6 19 Qa4 f3 20 g3 h5 21 b5 h4 22 bxc6

12 Bd3 Bxf5 13 exf5 Nf4 14 Bxf4 exf4 15 Re1 0-0-0 16 c3 Nf6 17 b4 g4 18 Rb1 Bd6 19 Qa4 f3 20 g3 h5 21 b5 h4 22 bxc6

22…hxg3 23 hxg3 Bxg3 24 Rxb7 Bxf2+ 25 Kxf2 Qh2+ 26 Ke3 Qh6+ 27 Kf2 Qxd2+ 28 Re2 Ne4+ 29 Bxe4 Qxe2+ 30 Kg3 Qh2+ 0–1

22…hxg3 23 hxg3 Bxg3 24 Rxb7 Bxf2+ 25 Kxf2 Qh2+ 26 Ke3 Qh6+ 27 Kf2 Qxd2+ 28 Re2 Ne4+ 29 Bxe4 Qxe2+ 30 Kg3 Qh2+ 0–1

The game is deeply annotated in my book.

‘The last throes’ is a phrase that conjures up images of prolonged suffering, pain and anxiety. In the hypermodern sense this condition has been brought about as a consequence of committing the pawn to the e4 square, which might cause permanent damage, not only because the pawn itself can be continually attacked and perhaps eventually destroyed but also because the adjacent squares on d4 and f4 have been weakened, even more so if White then advances c2-c4 or g2-g4. On top of all this, Black has the potential pawn break …f7-f5, undermining the e4 pawn and possibly opening the f-file and/or lengthening the a8-h1 diagonal for a black fianchettoed queen’s bishop.

In Magyar Sakkvilág, when annotating a consultation game played at the Budapest Chess Club in 1916, Breyer, referring to himself, added the following witty note after 1 e4:

‘A commentator added two question marks to this move. Why? He didn’t give his reasons. The idea was probably just to immortalise his own name, like Herostratus burning down one of the Seven Wonders. In fact he failed in his objective. As a chess professional I ought to have his name firmly lodged in my memory . . . but I have to admit I’ve forgotten it.’

Then again Breyer adds, apropos ‘the last throes’ theme:

‘It’s clear that after 1 e4 White’s game isn’t irrevocably lost, but if Black avails himself of the most promising means of defence at his disposal – a counterattack – then things can get uncomfortable. It’s understandable that masters today increasingly prefer 1 d4.’

To illustrate what he meant by ‘counterattack’, Breyer initially advocated, in reply to 1 e4, the move 1…e6 followed by 2…b6 and 3…Bb7 hitting the e-pawn straight away.

Nevertheless, Breyer did not give up on 1 e2-e4, but later followed it up with 2 d2-d3, to deal with the vulnerability of the e-pawn, whilst storing up energy, as he did for example against the Caro-Kann, French and Sicilian defences. ‘Overprotection’ in its purest form! And a forerunner of the King’s Indian Attack.

Mentioning these things would have gone some way to clearing up the reason for the question mark(s) Breyer attached to the move 1 e4, as well as his views on the subsequent position. But Ed. Winter didn’t include anything like this in his ‘feature article’.

Instead he devotes a fair amount of space to citing various writers who have repeated ‘the last throes’ comment or interpreted it in their own individual way, but to me it seemed pointless to give all these derivatives when I had already quoted from the original source, which was all that really mattered. Having said that, however, near the end of the book I gave extracts from a very perceptive book, Chess of Today, published in 1924, where Alfred Emery presents a contemporary overview of the influence of hypermodern chess.

Here he interprets ‘the last throes’ statement as ‘White’s game is in the last stage of disintegration’, which is as good a version as any, whilst admitting that ‘Breyer may have been pulling our legs’. Again, no mention of this by Ed. Winter.

His very same article also contains the correspondence from Mr A. Eccles, but this gentleman clearly had no knowledge of German and Hungarian texts and only used Reti’s Modern Ideas in Chess as his point of reference, so I did not include his material as it was already covered in the book by original sources.

Then again Ed. Winter reproduced a claim by P.W. Sergeant, author of A Century of British Chess, who, when reviewing Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess, had written in the BCM:

‘Breyer is quoted as saying that “after 1 e4 White’s game is in its [this should really be ‘the’] last throes” but this is scarcely hyper-modern, H.E. Atkins made a similar joking remark to the present reviewer, if his memory is not at fault, 25 years ago.’

Well, I suppose, if it was just a ’joke’, and nothing else, then it carries no weight.

This was followed by Ed. Winter quoting Zsigmond Barász: ‘As far as I can remember, it was Mieses who made the piquant remark that 1 e4 is a mistake which leads to the loss of a game’. The fact that the remark was ‘piquant’ (or spicy!) and Mieses was a king’s pawn player all his life makes this pretty unconvincing too.

In both these cases the writers do not appear to fully trust their memory and are relying on ‘once said’ statements, which Ed. Winter usually dismisses out of hand.

Therefore I disregarded these items as neither was backed up with any evidence or reasoned arguments. Again, they represented just the sort of thing that usually arouses Ed. Winter’s scepticism, and even rejection, so I don’t know why he is so keen to promote them in his ‘feature article’.

By contrast, Breyer goes to great lengths to lay his cards on the table and explain to readers how he came to his conclusions, as is amply demonstrated by his articles in the book.

There is a parallel here when names of openings are credited to players who supposedly were the first to play them but are less deserving of being honoured in this way than those who came later and did real work on the specific ideas, plans and variations. Such injustice even prompted Mikhail Chigorin to make fun of the naming of the Caro-Kann Defence:

‘Caro played 1…c6 and Kann 2…d5.’

And that’s all folks!

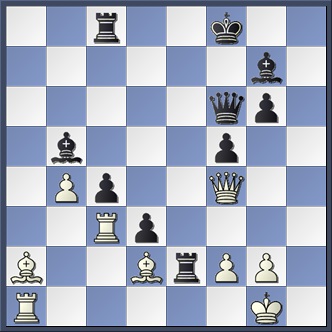

Incidentally, also in the book, there is a very early game by 18-year-old Boris Spassky, a pioneer in playing the Breyer Variation of the Ruy Lopez. Here he highlights the potential weakness of the white pawn on e4 and, by systematically carrying out all the necessary operations, finally ‘paints the centre black’ by total domination and occupation.

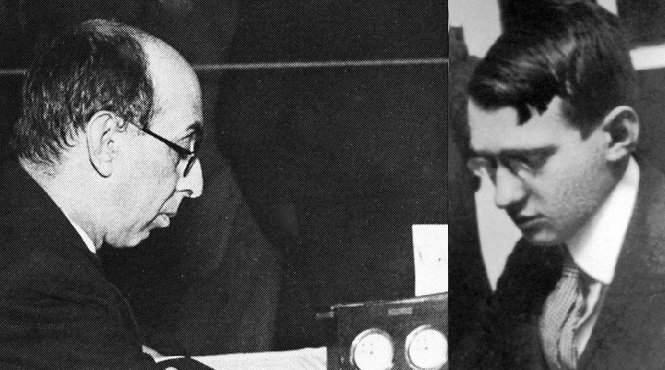

Boris Spassky was the first grandmaster to play the Breyer Variation of the Ruy Lopez

World Students Team Championship, Lyon 1955

34…Nxe4!

The white e-pawn finally falls.

35 Nxe4 f5 36 Qe2 Rxe4 37 Qf1 Qe6

Now that the white centre has been completely destroyed, Black’s pawns on c4 and d4 will bring about a quick decision.

38 b4 Bb5 39 Qd1 Kf8 40 Qf3 d3 41 Rc3

Tantamount to resignation. But if 41 Bc3 Bxc3 42 Rxc3 Re1+ 43 Kh2 Rxb1 44 Bxb1 Qe5+ and wins.

41…Qa6 42 Ra1 Re2 43 Qf4 Qf6

Or 44 Rac1 g5! winning.

44…Rxd2 45 Rxd2 Qxc3 46 Qd6+ Kg8 47 Rd1 Kh7 48 Qh2+ Bh6 49 Qd6 Re8 50 Qc7+ Qg7 51 Qc5 d2 0–1

The chess revolutionary would surely have been very proud to see his opening invention being taken up, and its principles being realised in practice, by a future world champion!

There is, though, a full page quoting Larry Evans (source specified: ‘From New Ideas in Chess’). Anyone who turns to Evans’ final edition of that book (Las Vegas, 2011) will find, on pages 25-29, a substantially different text, and it is therefore necessary to go back to the original edition (New York, 1958). The text quoted by Adams is on pages 12-15, but much of it has been silently excised from the Breyer book.

Yes, I included a streamlined version of Larry Evans’ item on hypermodern chess, taken from his highly instructive manual New Ideas in Chess, which, incidentally, was the first chess book I ever owned, having won it as a prize and become a London Junior Champion a short time after reading it! I also included a similarly tailored historical piece by Max Euwe on the same topic.

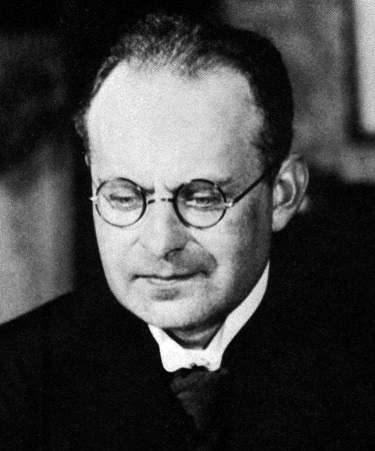

Former world champion Max Euwe was a contemporary of Gyula Breyer and acknowledged his importance in his book The Development of Chess Style

There was some overlap in content with these two extracts and so I edited them to avoid duplication and to eliminate text which was too far removed from Breyer himself. In my opinion, both of these articles really got to the heart of what hypermodern chess was about and were presented in a clear and succinct manner.

It seems to me that Ed. Winter is not satisfied unless such extracts are quoted in their entirety, whether all the content is relevant or not. For example, in the Las Vegas edition of New Ideas in Chess, published in 2011, the year after Larry Evans died, additional material has been added on Nimzowitsch.

The credo of fellow Hypermodern, Aron Nimzowitsch, was ‘Restrain, Blockade, Destroy’ whereas for Breyer it was more like ‘Confuse, Complicate, Counterattack!’

But I didn’t want data on him to be included in Larry Evans’ article because Max Euwe had dealt with Nimzo’s contributions to hypermodern chess already.

Then, because I am not quoting from the Las Vegas version of New Ideas in Chess, Ed. Winter says ‘It is therefore necessary to go back to the original edition (New York, 1958).’

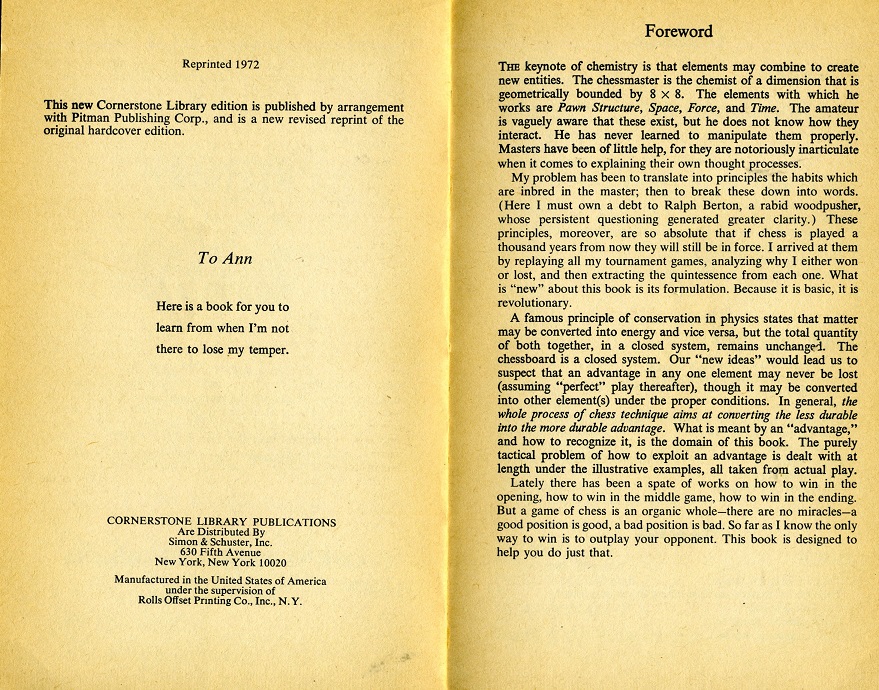

But in fact not only is it not ‘necessary’ to go anywhere, there is no need to go all the way back to 1958, since there is a Dover edition of New Ideas in Chess, published in 1994 which is still readily available in the bookshops.

This is the same as the original 1958 edition, apart from a new introduction by the author.

This is the same as the original 1958 edition, apart from a new introduction by the author.

Incidentally, there was also a paperback Cornerstone ‘revised and reprinted’ edition, not mentioned by Ed. Winter and which hit the bookshops at the height of the Fischer-Spassky boom of 1972.

Funnily enough, when Larry Evans came to London to provide commentary for the Kasparov v Kramnik match in London 2000, I asked him to explain how it was that he dedicated the 1958 edition to Clementine, whereas in the 1972 reprint it was Ann who was so honoured. Without a moment’s thought, he quipped: ‘A man has got the right to change his mind!’

Funnily enough, when Larry Evans came to London to provide commentary for the Kasparov v Kramnik match in London 2000, I asked him to explain how it was that he dedicated the 1958 edition to Clementine, whereas in the 1972 reprint it was Ann who was so honoured. Without a moment’s thought, he quipped: ‘A man has got the right to change his mind!’

Meanwhile, I seem to recall an even later version, changing the dedication again, this time to Ingrid.

Larry Evans: ‘A man has got the right to change his mind!’

This whole business reminds me of a couple of verses from an old Wild West folk song:

Oh my darling, oh my darling,

Oh my darling, Clementine!

Thou art lost and gone forever

Dreadful sorry, Clementine

How I missed her! How I missed her,

How I missed my Clementine,

But I kissed her little sister,

And forgot my Clementine.

On the substantive issue of the alleged ‘last throes’ comment, Evans had merely a ‘once’ version in New Ideas in Chess:

‘Breyer once began annotating a game by giving 1 P-K4 a question mark, accompanied by the comment that ‘White’s game is in its last throes!’’

That is quoted without comment by Adams, who had nonetheless written on the previous page:

‘We have found no documentary evidence that Breyer really did make the ‘White’s game is in the last throes’ comment, although his articles effectively did send that message!’

I do not understand why he says ‘Evans had merely a “once” version’, as we have already pointed out that Breyer admits to censuring 1 e4 – admittedly not with one question mark, but with two! And, after all, Larry Evans is only quoting Tartakower on ‘the last throes’ comment. If Ed. Winter has a problem with that he should lay the blame on Tartakower (or maybe Réti), not Evans. As for my own remark, ‘. . .although his articles effectively send that message’, well, if a move is punctuated with two question marks then it is not unreasonable to suppose that things must look pretty bleak for that player.

Also Ed. Winter’s remark that I quoted Larry Evans ‘without comment’ is not true. On the ‘previous page’ where I gave the full text of Tartakower’s ‘the last throes’ article, which is the original source of this claim, he omits to mention what I wrote at the bottom, immediately preceding Larry Evans’ article: ‘We now offer just one more of countless references made over the years to the last throes. . .’ I wonder what further comment he expects me to make?

As noted in our above-mentioned feature article, Evans did not stand by his 1958 text, later coming up with a different account of the remark, with Breyer expunged and replaced by Réti. C.N. 6264 quoted from page 26 of the 1974 book Evans on Chess:

‘. . .Richard Réti, who in 1919 startled the chessworld by announcing that “White’s game is in its last throes” after 1 P-K4.’

Richard Réti wrote: ‘We all learned from Breyer’

In the longer term, Ed. Winter is wrong in stating ‘Evans did not stand by his 1958 text’, since in the Dover edition, published in 1994, as well as the Las Vegas version of 2011, Breyer and not Réti is given as making ‘the last throes’ statement. Also the Cornerstone edition retains Breyer’s name, and this came out in the middle of the period covered by Evans on Chess.

Evans on Chess, published in 1974, is a collection of Larry Evans’ newspaper columns from 1971-73. Réti was a prolific newspaper columnist too and it was from such writings that the German and English versions of his classic book Modern Ideas in Chess, published in 1922 and 1923, were born. It is quite possible that Réti first ‘announced’ the last throes in one of his columns during 1919, at which time he was living in Holland and writing for a Dutch newspaper, but whether or not he stated that he himself and not Breyer made ‘the last throes’ comment requires further research. I personally have not found anything to this effect in my investigations. But if Larry Evans was somehow swayed into believing Réti did make the claim, this view was only temporary, since all future editions of New Ideas in Chess remained constant in declaring Breyer as the author of ‘the last throes’ comment – even when these editions included other revisions.

A book on Breyer which pays attention to the output of Larry Evans, quoting him as if he were a credible authority, is asking for trouble.

I don’t know exactly what Ed. Winter means by ‘as if he were a credible authority’. Larry Evans was a strong grandmaster and 5-times US Champion, so his chess-playing credentials are not in doubt. Moreover Ed. Winter does not say what the ‘trouble’ is with his article on hypermodern chess. The extracts from the books of Larry Evans and Max Euwe each provide a modern and objective retrospective view of what hypermodern chess stood for and what it achieved, which is why I included them. I particularly liked the following statement by Larry Evans in New Ideas in Chess, which sums up Breyer’s approach to chess perfectly:

‘Classical theory was so entrenched by the time they appeared on the scene that the Hypermoderns were forced to overstate their case in order to be heard. By bending the stick to one side, they helped to place it in the middle. Their imperishable message is to keep our eyes open, to avoid routine, and to approach each position with an open mind.’

Incidentally, from the Breyer index (page 866) it is not immediately clear that Evans is mentioned in the book at all, since the reference to him on page 696 is among a list of page numbers (not all accurate) concerning the Evans Gambit.

Actually, I didn’t compile the index, it was computer generated. But the computer did not have the human intelligence to distinguish between the gambiteer and the grandmaster.

As Larry joked: ‘Captain Evans died a hundred years ago and has been living off my reputation ever since!’

Don’t miss the final installment which translates Breyer’s epitaph ‘Credo, quia absurdum’ into understandable English!

Jimmy Adams, Thanks for this great reply. I am thoroughly enjoying your book on Chigorin and interested in your book on Breyer. Your response to Winter’s is interesting from a historical perspective. His readings leave me with a feeling of being “in my last throes,” as I don’t see the need to contradict everyone unless you can do so with precision. But he has put himself into this role of chess historian and so it would hardly be in keeping with this career to comment that any book is thought-provoking and accurate.