Samuel Lipschütz: A Life in Chess

Stephen Davies

408 pages | hardback | 42 illustrations | 249 games | $65.00

Jefferson: McFarland, 2015

Hans Renette

Samuel Lipschütz

It does not take much to fire a passion. In his introduction to Samuel Lipschütz: A Life in Chess, Stephen Davies relates how he became fascinated by Lipschütz’s name, which ultimately led him to write a biography on this nearly forgotten nineteenth-century master. The result is one of the finest chess biographies around.

This beautifully produced hardback is published by McFarland & Company, Inc., a household name to lovers of chess history (they have more than sixty of such works in their catalogue). Although McFarland’s output has focused on the ‘big names’, with biographies of players like Capablanca, Alekhine and Botvinnik, it has an impressive list of American subjects, some of whom, like Walter Penn Shipley and Julius Finn, are of national importance at best. Earlier reviews of Davies’ book give the impression that Lipschütz falls into the same category but in fact he surpasses them easily.1 In his introduction Davies rightly summarizes that

‘Lipschütz was the most prominent American chess master for only a short period, from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s, but he played a supporting role on the world stage of chess: he played against and was on friendly terms with two world champions, William Steinitz and Emanuel Lasker . . . He also played against five other men who contested matches for the official world championship . . . Further, Lipschütz was a prominent figure in the New York Chess scene for most of the 20 years after he joined the Manhattan Chess Club in 1883.’ [Davies, p.3]

Lipschütz’ forename has provoked debate over the years. Davies has already contributed to the discussion,2 and here he enumerates with characteristic precision how and where the various candidate names were used. All in all, it seems fair to opt for the anglicized ‘Samuel’ of the book’s title. Salomon/Solomon was probably the form used by Lipschütz’ countrymen and family.

Samuel Lipschütz was born in 1863 in Ungvár (nowadays Uzhhorod in Ukraine) in the Kingdom of Hungary, a part of the Austrian Empire. After his mother’s death he, his father and his brothers travelled to the United States one by one and settled in New York. Davies has unearthed several obscure details about this relatively poor migrant family to paint a broader picture of the society they lived in.3

Lipschütz learned the rules of chess when he was about 13, working in Hungary as a printer’s apprentice. These activities would define his life, for in the States he continued the same professional work while devoting his leisure hours to his favourite pastime.

The visits of Steinitz and Zukertort to the United States, in 1882 and 1883, boosted the game’s popularity, in much the same way Fischer did nearly a century later. It was the stimulus Lipschütz needed to join the Manhattan Chess Club at the end of 1883. It was the start of a meteoric career. He gained third prize in the sixth handicap tournament of the Manhattan Chess Club, where he received the odds of pawn and move from some of the strongest players in the country (notably Mackenzie and Delmar). In 1885 Lipschütz joined the New York Chess Club as well and became club champion.

In his earliest known games Lipschütz adopted a wild playing style, but quickly it becomes clear that he adhered to the modern chess school and was clearly influenced by Steinitz. The following game is a good example of his play at the time.

E. Delmar – S. Lipschütz

New York 1885

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d3 d6 6 b4 Bb6 7 a4 a6 8 a5 Ba7 9 Bg5 0–0 10 Qb3 Qe7 11 Nbd2 Nd8 12 Nf1 Ne6 13 Be3 c6 14 Bxa7 Rxa7 15 Ne3 Nf4 16 g3 Nh3 17 Nh4 g6 18 Qd1 Rd8 19 Qd2

The cause of his problems. Lipschütz’ reaction is very powerful.

19…d5 20 exd5 cxd5 21 Bb3 d4 22 Nc4 dxc3 23 Qxc3 Nd5 24 Qxe5 Qxb4+ 25 Nd2 b5 26 Qb2 Bg4 27 Kf1 Re7 28 Ne4 Rxe4 29 dxe4 Qxe4 30 Rg1 Nc3 31 Re1 Be2+ 32 Rxe2 Qxe2+

Wishing to simplify matters, but missing the quickest win: 32…Nxe2 33 Qxe2 Qxe2+ 34 Kxe2 Nxg1+ etc.

33 Qxe2 Nxe2 34 Rg2 Nc1 and Black won in the end.

Lipschütz’ career really took off in 1886. With the support of the New York Chess Club, he went to London to play in the congress of the British Chess Association. After a slow start he beat George Henry Mackenzie, the strongest American master, and some of the world’s leading players. His play during this tournament was typical: positional, sometimes tactically flawed, but with a combativeness that makes his games still interesting to play over. Shortly after their return, Lipschütz and Mackenzie contested a small match at the Manhattan Chess Club. Lipschütz lost narrowly, but an examination of the games clearly shows that he deserved more. Davies found out that Mackenzie didn’t put his title of American Champion at stake.

In 1889, most of the world’s strongest players gathered for the Sixth American Chess Congress. Because Lipschütz had won their congress in February, the New York State Chess Association paid his entrance fee. He excelled himself. After a testing two months, during which at least 38 games had to be played (draws in the second cycle were replayed, and Lipschütz had five of them), he finished sixth. He was the best American player and the only American prize winner. I was most struck by a great move he played in his first-round game against Pollock.

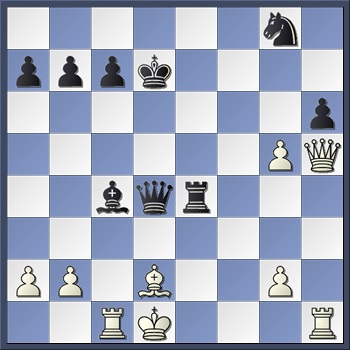

New York 1889

The position is level, but Black misjudges the situation.

21…Qxc2 22 Rf1!

A very strong, silent move. Suddenly Black’s king is in jeopardy.

22…Qh7 23 Qe7 Qh6 24 h3 h4 25 Kh2 Qe3

There is nothing better.

26 Qxe6+ Rd7 27 Rf3 Qe1 28 Qf5 Kc7 29 Qc2+ Kd8 30 Qc5 1–0

Steinitz praised the next game as ‘an excellent specimen of modern style’. Today’s players will find it instructive.

D.G. Baird – S. Lipschütz

New York 1889

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 0–0 Be7 5 Bxc6+ bxc6 6 d4 exd4 7 Nxd4 Bd7 8 f4 Nf6 9 Nc3 0–0 10 h3 c5 11 Nf3 Bc6 12 Re1 Re8 13 f5 Rb8 14 Rb1 Qc8 15 Kh2 Bf8 16 Qd3 Qb7 17 Nd2 Re7 18 b3 Rbe8 19 Bb2

19…d5 20 e5 Rxe5 21 Nf3 Rxe1 22 Rxe1 Bd6+ 23 Kh1 Rxe1+ 24 Nxe1 d4 25 Nd1 Be4 26 Qd2 Qd5 27 c3 Qxf5 28 Nf2 Bg3 29 Kg1 Bf4 30 Qd1 Be3 31 Qe2 Nd5 32 cxd4 cxd4 33 Nf3 Bxf3 34 Qxf3 Qxf3 35 gxf3 Nf4 0–1

Lipschütz was not able to build on the high reputation he had gained in New York. He beat Eugene Delmar in a match that was generally considered to be of low quality, but in tournaments he was superseded by Jackson Whipps Showalter and Albert Beauregard Hodges. The following offhand blindfold game, played at Showalter’s house, shows his tactical side.

S. Lipschütz – J. Showalter

Georgetown 1890

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 d5 4 Bxd5 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 g5 6 Nf3 Qh5 7 h4 h6 8 Bxf7+ Qxf7 9 Ne5 Qg7 10 Qh5+ Ke7 11 Ng6+ Kd8 12 Nxh8 Qxh8 13 hxg5 Nc6 14 c3 Be6 15 d4 Bc4+ 16 Ke1 Kd7 17 Bxf4 Re8 18 Nd2 Nxd4 19 cxd4 Qxd4 20 Rc1 Bb4 21 Kd1 Bxd2 22 Bxd2 Rxe4

23 Rxc4 Qxc4 24 gxh6 Qa4+ 25 b3 Qxa2 26 Qf5+ Re6 27 h7 Qa1+ 28 Bc1 Qd4+ 29 Kc2 Ne7 30 Qd3 Rc6+ 31 Kd2 Qxd3+ 32 Kxd3 Ng6 33 Bb2 1–0

Showalter (courtesy of Kevin Marchese, who is writing his biography)

In April 1891, Captain Mackenzie died, leaving the American chess scene without a clear champion. In the months and years that followed, there were various tournaments, matches, negotiations and behind-the-scenes manoeuvres to find the new champion. Davies relates the story skilfully (he is one of the first to do this), offering us many details and background information. First Showalter claimed the title, by defeating Max Judd, but then Lipschütz took the lead, beating Showalter decisively (7-1). The quality of these games, and of Lipschütz’ games in subsequent years, was however rather poor. By this time his weakening health had prompted to move to the American West Coast where the climate was kinder.

Lipschütz facing Sterling, New York Daily Tribune, 13 October 1895

On his return to New York, in 1895, Lipschütz was beaten by Showalter in a rematch. For the rest of his short life he restricted his playing activity to New York. After years of poor form, Lipschütz regained his strength around the turn of the century, scoring some fine results in tournaments and twice beating Frank Marshall 3-0. In exhibition games he was able to put the world champion, Emanuel Lasker, to the test.

But then his health declined again. Lipschütz left for Hamburg where he underwent several operations, only to die at the untimely age of 42.

In his preface, Davies writes how he realized that he ‘was standing on the shoulders of my forebears in the field of late 19th century American chess history and I hope this account of Lipschütz’s life, milieu and chess career proves to be a worthy complement’ (Davies, p. 1), thereby acknowledging earlier biographies such as John Hilbert’s on Albert Hodges. Davies’ book is indeed a worthy one, and bears comparison with them. He more than succeeds in portraying Lipschutz’ life vividly. His narrative is sober and fascinating. He does not overburden it with detail (e.g. biographies of each and every opponent) and he avoids digressions that might add colour at the expense of readability. Yet Davies has an eye for the telling anecdote. There is the beautiful description of Steinitz (p.14) and the story of how the operator of the automaton Ajeeb was beaten, outsmoked, by a weak opponent (p.22).

Lipschütz spent almost his entire career in New York and its environs. Only twice did he meet the world’s elite, in London 1886 and New York 1889. Both of these chapters are wonderful, especially the latter. It is the best piece written on this massive tournament that I have seen and Davies succeeds in coming really close to his subject. Again he gathers information from a huge variety of sources to trace the origins of the tournament. He describes its course with several well-chosen, often sparkling sketches; yet he never loses sight of Lipschütz.

On a few occasions, however, Davies could have strengthened the book by interrupting its rigidly chronological flow. The first two congresses of the United States Chess Association, for example, appear somewhat randomly (on pages 85 and 148). Had they, and more background information been included in the seventh chapter, which deals with the third congress featuring Lipschütz, the reader would had had a more complete understanding of how they were run.

Davies could also have made more of the fascinating relationship between Lipschütz and Steinitz.

Hints and quotes pervade the book:

- On p.19 Davies quotes the New York Evening Telegram of 13 June 1885, saying that Lipschütz ‘is a typo upon the International [Chess Magazine, Steinitz’ magazine], and in wrestling with Steinitz’s manuscripts has gone through a severe but valuable chess training’. This fascinating extract connects Lipschütz’ profession with the influence Steinitz had on his chess, and yet it is left hanging.

- Somewhat out of the blue, the quarrel between Steinitz and Samuel Loyd, unwittingly sparked by Lipschütz (pp.42-45).

- Lipschütz as a pupil of Steinitz (p.154).

- A training match between Lipschütz and Steinitz (p.200).

All this information is presented chronologically in a dispassionate way, without any attempt to knit the threads together.

The book is very accurate. There are no footnotes but almost every claim is supported by references to sources in the text itself. Davies provides tournament tables for the most important events in Lipschütz’ career, but a few minor ones are missing.

Davies presents the games with a mix of contemporary and modern notes. Lipschütz’ ascendancy coincided with Steinitz’ International Chess Magazine, and thus the reader will benefit from the large number of games annotated by Steinitz, who as an analyst was in a class of his own in the nineteenth century. Davies has checked the notes to each game for errors that ‘mostly concern tactical possibilities’. He regularly offers insight into the ideas behind moves as well, an excellent practice that encourages the chess student to play through the games. At times, however, Davies’ notes are superfluous, notably when he discovers a superior alternative in a position that is already won. We were not impressed by his excessive, and not always judicious, deployment of question marks. See, for example, game 69 where only Black is awarded question marks (three) even though he wins the game.

All in all, this is one of the best biographies of a nineteenth-century chess player I have read. Davies has written an excellently researched, readable book, filled with untold stories and related information.

It is one of the first books to examine the struggle for hegemony in American chess that took place after Mackenzie’s death in 1891, and Davies does it with great skill. The games vary in quality but are certainly not devoid of interest. Though largely unknown today, Lipschütz deserves such a tribute, given his status as American Champion and one of the strongest players of his day.

Notes

- ‘Two – Ignaz Kolisch … and Samuel Lipschütz … – are first rate works on fine but lesser-known players.’ Chess Life, review available at https://chessbookreviews.wordpress.com/2016/04/05/biographies-from-mcfarland/. This review mainly deals with books about Blackburne and Capablanca, offering the other two books no more than this one line. Kolisch, besides having an extremely attractive playing style, could have claimed to be the world’s strongest player after the Paris 1867 tournament; Lipschütz could also count himself in the world’s top ten (although such a concept is a bit too modern to apply to the nineteenth century).

- See http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/lipschuetz.html.

- We won’t dwell on Davies’ research into Lipschütz’ personal life in this review, but he does it very well (e.g. on Lipschütz’ health troubles and professional activities).

Hans Renette’s book, H.E. Bird: A Chess Biography with 1,198 Games will be published by McFarland in October.