‘Everything about our situation was a riddle. Why would Karpov and three of his colleagues jump on a plane and fly hundreds of miles to Kalmykia to open a criminal case against me just for revenge?’

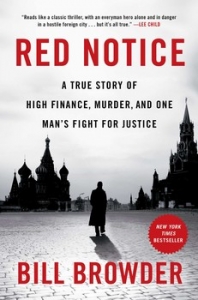

Bill Browder, Red Notice: How I Became Putin’s No. 1 Enemy (London: Transworld, 2015), p. 217.

This Karpov isn’t Anatoly, but Pavel, a Moscow policeman who conspired with other state officials in 2006 to defraud Russia of $230 million of taxpayers’ money.

Kalmykia is ‘a southern Russian republic on the Caspian Sea populated by Asiatic Buddhists’ that played a key role in the fraud [Browder: 215].

American investor Bill Browder tells the story of the theft in his gripping indictment of Putin’s Russia published last month.

Karpov and his accomplices tried to frame Browder for their crime:

‘The Russian authorities were charging me with two counts of tax evasion in 2001. Kalmykia had tax breaks not unlike those in Jersey or the Isle of Man, and the fund had registered two of our investment companies there. The case was clearly trumped up.’

[Browder: 216]

Karpov’s men went on to torture to death Browder’s lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, the man who uncovered the fraud. Browder’s campaign to seek justice for his friend led to the US government passing the Magnitsky Act which prevents the Russian officials responsible for Magnitsky’s death from travelling to the United States and from using its banking system.

That Kalmykia features so prominently in the story is a reminder that the criminal activity of its erstwhile president Kirsan Ilyumzhinov extends far beyond the chess world. Chess publications rarely mention that the source of the FIDE president’s wealth was a massive tax fraud:

‘Kalmykia’s offshore system was closed by federal authorities after a prosecutor’s report of 29 August 2002 concluded that few taxes had arrived in federal coffers from the Kalmyk-registered companies, and that: “As a result, 4.238bn roubles have not been received by the federal bank during the year 2000 … and 6.295bn in 2001.” Moreover, “Criminals are using this system to commit their illegalities of a regional, inter-regional and international character, doing grave harm to Russian state interests.” Kalmykia is now liable to Moscow for the missing taxes, which the opposition estimates at some 20bn roubles.’

Ed Vulliamy, ‘The man who bought chess’, Observer, 29 October 2006

At that time (2006) 20 billion roubles was worth around £500 million. Ilyumzhinov cut a deal with the Kremlin to limit the damage and pay off some of the debt. That’s the way Putin likes to operate:

‘After Khodorkovsky [a businessman Putin imprisoned for fraud in 2005] was found guilty, most of Russia’s oligarchs went one by one to Putin and said, “Vladimir Vladimirovich, what can I do to make sure I won’t end up sitting in a cage?” I wasn’t there, so I’m only speculating, but I imagine Putin’s response was something like this: “Fifty per cent.”

Not 50 per cent to the government or 50 per cent to the presidential administration, but 50 per cent to Vladimir Putin. I don’t know this for sure. It could have been 30 per cent or 70 per cent or some other arrangement. What I do know for sure was that after Khodorkovsky’s conviction, my interests and Putin’s were no longer aligned. He had made the oligarchs his “bitches”, consolidated his power and, by many estimates, become the richest man in the world.’

[Browder: 163]

It’s one reason why these days Ilyumzhinov is taking from FIDE’s coffers rather than contributing to them.

We must not forget journalist Larisa Yudina: Ilyumzhinov’s Sergei Magnitsky.

Presciently she characterised Ilyumzhinov as ‘a Khan, charming abroad but vengeful at home. If you are against him, that’s it.’ She disappeared in 1998 while investigating his offshore tax haven scam. It was a contract killing:

‘Yudina was not the unlucky victim of a mugging. She received a phone call from a man who offered to give her proof that money had been embezzled by the state company she was investigating. She got into a car to meet him, was driven away, and never seen alive again.’

Sarah Hurst, Curse of Kirsan: Adventures in the Chess Underworld, p.175

In 1999 Sergei Vaskin, an adviser to Ilyumzhinov, and a gangster called Vladimir Shanukov confessed to the murder and were sentenced to 21 years in prison but there is still doubt as to whether they were the perpetrators.

As Yudina’s husband, Gennady, said at the time:

‘The killers and others have given evidence, pointing at political circles. One witness, who is no longer alive, has alleged that President Ilyumzhinov’s brother was in Yudina’s flat on the evening she disappeared. The official police investigation, however, has been closed and the public prosecutor refuses to re-open the case.’

[Hurst: 187]

The scandal should have done for Ilyumzhinov in the 2002 Kalmyk elections but he survived despite opposition from Gennady Yudin and Boris Nemtsov.

There was no wealthy American businessman to seek justice for Yudina and her family.

And the chess world turned a blind eye.

Sources

Sarah Hurst, Curse of Kirsan: Adventures in the Chess Underworld (Milford: Russell Enterprises, 2002).

Bill Browder, Red Notice: How I Became Putin’s No. 1 Enemy (London: Transworld, 2015).

Ed Vulliamy, ‘The man who bought chess’, Observer, 29 October 2006.

Thank you for an interesting article about our republic. We don’t get to read a lot about criticism of Kirsan. As this is my personal name, too, I am very interested in what image he has. Everyone thinks about him, when they hear my name. It is important to bring those things up, anyway. Thank you once again and greetings from Kalmykia.