Andy Lewis

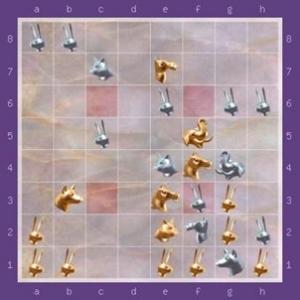

A common Arimaa starting position

Anyone for a variation on chess?

Is chess played out?

This concern has been voiced periodically over the history of the game, and the challenges has never been more profound: over-refinement of opening-theory; perfection of endgame technique; super-abundance of draws at top-flight level; and (most recently) dominance of chess computers.

To best ensure the future survival of the game, the great and the good have, over the years, proposed a number of variants to the rules of chess.

For example:

- Randomizing the starting position (Fischer)

- Adding extra pieces (Capablanca and Seirawan)

- Pawn-division (Regan)

- Redefining stalemate as victory (Short).

Although not without academic interest, there is one problem which each of these chess simulants suffers from: it’s just not as good as the real thing! We know it. And their inventors know it too.

This is amply demonstrated by the lack of enthusiasm shown even by their originators. If you feel that your chess-variant is worthy of interest, then, by all means, start a web-site, develop a smart phone app, get sponsorship, organize a tournament, re-write endgame theory, publish a book of studies. But, if these are too much trouble for you, then, for heaven’s sake, you might at least play the game yourself!

Tinkering with the rules of chess is like adding a harmonica or a ukulele section to a classical orchestra: it’s pointless. And sounds awful.

What is Arimaa?

Arimaa is a radical re-invention of chess. It has been around for just over a decade. It’s played between two players on a 64 square board, with the same number of pieces. It could be played with a standard chess-set and board.

The pieces are named after members of the animal kingdom: ranging from the mighty Elephant to the humble Rabbit.

Although completely different, it is easy to teach a chess player the basics of Arimaa in about 10 minutes. For those of you who don’t the rules, you can find a potted summary in Appendix A and a canonical statement of the rules on the Arimaa Wikipage.1

Is there Arimaa opening theory?

Nope. There is none as we chess players understand this concept. Why?

Firstly, there is no pre-defined starting position. Arimaa players get to choose their initial distribution of forces.

Secondly, even if Arimaa converged on an “optimal” starting position, variation branching kicks in much earlier and much harder.

Chess gives White 20 possibilities on move 1, rising to a maximum of +50 in some crazy open-board middle game positions. However, the average Arimaa position gives the player a stupendous 17,000 options for completing his turn.

This arises because although individual Arimaa piece moves are much simpler than chess, an Arimaa turn consists of four sub-moves. Power that up a few times, and it’s easy to see that discussion of exact (specific) positions (chess-opening style) is never going to have any practical relevance.

That said, categorization and discussions of (abstract) types of opening and early middle game positions is a realistic possibility for Arimaa – it’s just that no one has got around to working on that yet. This would be along the lines of Euwe and Kramer’s two-volume treatise,5 and is top of my wish-list for the next Arimaa book.

Is there Arimaa endgame theory?

Tricky question. As an Arimaa game progresses, pieces drop off, and the board thins out. So shouldn’t there be an Arimaa endgame discipline to counterpart that of chess? Big, thick books by Reuben Fine, unreadably tedious books by Dr John Nunn. Tablebases. All that sort of stuff. Right?

Wrong. Chess tends to simplify as more pieces are exchanged, enabling greater precision in planning and long-range calculation. But paradoxically, the more that pieces come off, the more tactically complex Arimaa becomes! Why is this?

The explanation relates to the deepest difference between this game and every other chess variants.

Arimaa has no King-piece. Rather, the objective of the game is distributed across those pesky little Rabbits.

What is the effect of piece reduction in Arimaa? If you have removed some of your opponent’s Rabbits, then you are that bit closer to eliminating all of the rest. (And Elimination wins the game.) If however, he is now short of other pieces, he has less armour to put in front of your Rabbit’s path to his back rank. (And Goal also wins the game.) Just like chess, the closer you are to finishing off the opponent, the more important concrete, tactical calculation becomes. In Arimaa, material and positional advantage, trap defence, centralization can all go straight out of the window when Goal or Elimination are in sight.

So unlike chess, discussion of general cases in Arimaa endgames means next to nothing. There is no point in discussing, in abstract terms, whether Elephant + Camel + Cat + 2 Rabbits v Elephant + Horse + Cat + 4 Rabbits is a win or not. Everything is going to hang on just where those Rabbits are!

And there is another reason why Arimaa Endgame theory is going to be less important. In chess, the basic technique for realizing a material advantage is simplification by exchanges. Forced simplification commonly occurs when one piece attacks another of equal value, which is defended by a friendly piece. But no equivalent to this technique can exist in Arimaa

Chess-style captures are impossible. In Arimaa, pieces can only get removed from the board by getting dragged into those menacingly darkened “trap” squares.

Equal exchanges occur in Arimaa when (e.g.) Gold threatens to drop a piece into a trap, and Silver counters not be removing the piece or defending this trap, but by countering with a threat to drop an equivalent piece into another trap. This is a more complex process than exchanging in chess, and is considerably less forcing.

The upshot is that the Arimaa player fortunate to find that his opponent has just hung his Rabbit is not going to be able to rely on simplification as a direct approach to win him the game. Rather, he is going to have to play in much the same fashion as he did without his extra material: controlling traps, making pseudo threats, wearing out the opposition. Hoping that his extra Rabbit is going to be worth something, but not necessarily counting on it.

How about Arimaa swindles?

Arimaa abounds in tactics: particularly after exchanges (even unequal exchanges).

Arimaa therefore offers a fertile ground for the swindler, which the Arimaa sub-culture positively encourages. Resignations, even (or perhaps especially) in top-rank Arimaa games are frowned upon, and player continues to fight until the bitter end. Here is a classic.

Bomb – Omar Syed (US) 2007

Gold to play 37g

This is taken from the 2007 Computer (v Human) Challenge. Gold is Bomb (the No 1 bot at that time) and Silver is Omar Syed (inventor of Arimaa). Omar had been mercilessly cheapoed by Bomb, is suffering a severe material deficit (2 Horses for only a Cat) and is in deep farmyard manure.

First, note those heavy Gold pieces poised menacingly around the f6 trap, and the Silver Cat & Rabbits close by. Unless Silver does something radical, in just a few moves time, all of those weakling are going to be dragged into a deep pit. Next, note the advanced Silver Rabbit on h2, and the Elephant, Camel & Dog lurking nearby in the over-crowded SE corner of the board. This crew forms the slender basis of Silver’s remaining hopes.

With serene nonchalance, Bomb went after the Silver Cat with 37g Db3n Me7ww cc7s. Omar, doubtless sensing divine intervention, gratefully replied with 37s eg4s Rg3e eg3n Rg2n arriving at the position below.

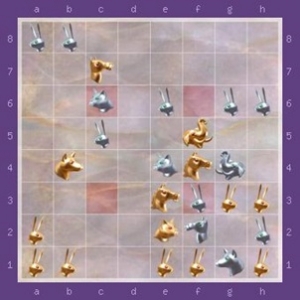

Bomb – Omar Syed 2007

Gold to play 38g

To the novice it might seem as if the shuffle in the SE quadrant has changed nothing: the Rabbit on g2 has shifted to h3 and a gap has opened up on g2. So what? But to an experienced Arimaa player, it’s the biggest difference in the world! That gap on g2 is the only window of opportunity the Silver Dog on g1 needs to pull the Rabbit from h1 to g1, freeing up the one space needed for the Rabbit on h2 to reach h1. No other calculation is needed: goal is unstoppable on the next move. Game, set and match to humanity.

You can read an expanded analysis of the final sequence of moves in Beginning Arimaa (pp.26-8)3 and it was this section which first made me think that Arimaa had something different to offer. Bomb was the top rated engine between 2004 and 2008, and yet misses a threat to end the game in only 2 moves! In 2007? Inconceivable!

When was it last that computers were unable to recognize a checkmate in 2? Wasn’t that before England won the World Cup?

Why can’t computers play Arimaa?

The revelation that computers don’t play Arimaa terribly well is pretty counter-intuitive: especially given that Arimaa was invented by a computer scientist, and has been studied by the AI community for all of its 13 year existence. So how good are the bots? A rank beginner would come into the Arimaa Game world with an initial rating of 1000, but with talent might aspire to reach a rating of 2000 after a year or so with +500 games practice. Currently the world’s top rated (human) player is 2700. By comparison, the top bot is rated only around 2500.

However, the difference is actually larger than these ratings suggest. The annual Computer Challenge match has been held since 2004, each time resulting in a clear victory to carbon based life forms. And the margin isn’t narrowing. Omar Syed (who organizes the yearly bot-flaying fest) arguably doesn’t even need his A-team on the park to ensure a result for the humans. What’s up with silicon?

Firstly, to the human mind, Arimaa is very much like chess. Arimaa positions have a recognizable structure and abstract features. It is possible to explain why some moves are good and other not by reference to those features. Experienced Arimaa players latch onto those features, and see pretty quickly what is happening without having to calculate zillions of variations (or indeed sometimes any variations). But computers do not calculate based upon abstract features, but only upon concrete variations.

There are zillions more variations in Arimaa than in chess. So the computer’s shabby trick of looking at all (or almost all) of the variations just doesn’t work anymore.

Secondly, the historically illiterate may be excused for thinking that the present pre-eminence of computers in chess is the mainly the product of recent improvement in computer hardware, not to mention the dexterity and cunning of arch-programmers. But we know differently: human beings had already achieved near-mastery of chess by, at least, the Karpov era (and arguably earlier) without recourse to silicon assistance.

Agreed, computers have hardened, productionized and distributed that knowledge, to an extent unimaginable 40 years ago: now even enabling the mass production of +2700 GMs, coming onto the chess market like so-many luxury cars. Sure, computers have taken the journey further then human beings alone ever could. And, yes, they are now dragging us up with them. But let us not forget who laboured to carry them every step of the way, except the final few metres to the summit.

By comparison, the conquest of Arimaa has not even reached the first base-camp. There are two quality books on the game, a great Wikipedia page and a database of all known Arimaa games. And (hats off to them) the Arimaa community had done a pretty decent job in getting all of this material online. But this is as nothing compared to the compendious chess literature, straddling 150 years of critical thinking.

If the computer ascent of Arimaa is going to happen in anything like the same fashion as chess, human Arimaa players need to get a lot stronger and a lot more articulate before the climb gets anywhere.

So, there’s an Arimaa World Championship. How does that work?

Arimaa is played almost exclusively online. There is absolutely no reason, in principle, why it could not be played head-to-head. But internet tournaments are a necessity, because right now there aren’t too many Arimaa players (the Arimaa website 4 lists around 500 active players world-wide) and these are scattered across the globe.

The annual Arimaa World Championship is open to all, and the entry fee is a surprisingly reasonable $10. The tournament style is a curious fusion of a Swiss with a KO. I’ll spare the reader the minutiae, but the way it basically works is that it starts off like a Swiss for the first 3 rounds, but then players are eliminated from contention for the title after they have suffered 3 loses. The rounds are continued, until only one player is left.

In 2014, there were 44 players, and it required just 12 rounds to produce the World Champion. This year, there’s a record 50 entrants. The schedule is a leisurely one game per week. The tournament started in January and is expected to conclude by mid-April.

The Arimaa time-controls work slightly different to that of chess. Each player has an initial allocation of time (say 5 minutes) which is incremented after each move by a set amount (say 60 seconds) as per the “Fisher” clock. However, unlike chess, the Arimaa clocks caps the total time reserve that a player can accumulate (e.g. 5 minutes). So, no player can ever take more on a move that the defined maximum. You can argue the pros and cons of each approach. However, the Arimaa controls mean no move should ever be rushed (or mis-keyed) but keeps the game flowing. Arimaa World Championship games tend to last around 40 moves and complete in 1-2 hours.

Pairing is designed to accelerate the elimination process. This can be a little intimidating for the newbie. 2015 was my first year, and in Round 1, I was paired against the reigning World Champion! As a reward for my success in R2, I found myself paired against the no 1 seed in R3!

Looked at positively, it means that even newcomers get the chance to play the best in world.

In what chess tournament could a beginner expect to play both Carlsen and Anand? All for less than the price of a trip to Starbucks!

Who’s going to win in 2015?

Fritz Juhnke is the veteran to keep an eye on. Fritz was world champion in 2005 and 2008, and runner-up in 2009 and 2010. He has written one of the most entertaining books on gaming that I have ever read.3 Not just a smart guy, he’s also a nice guy and personally welcomed me to the Arimaa community when I joined. He doesn’t appear to be spending so much time on Arimaa as he once did (perhaps focusing more on his PhD thesis in Applied Mathematics). But make no mistake, he still play a mean game and can do it again this year.

Mathew Brown has the skill and the hunger to take the title for the first time. His appetite sharpened by the chagrin of his 2nd place in 2014, Mathew has been spending an awful lot of time in the Arimaa gaming room, honing his bot-bashing skills, frequently racking up runs of +20 consecutive wins. He’s fresh from his success in the 2014 postal championship with a phenomenal 16 of out 16. And as a back-up plan, has even entered a bot for the 2015 Computer Championship. That’s commitment for you.

Jean Daligault, however, is the man that everyone would want to beat, but almost no one can. Jean captured the title at his first attempt in 2007, and has been World Champion for six of the last eight years. And even on the years he didn’t win it, he was still second. So far ahead of the field, he’s found it necessary to author the definitive book on the game, to help us suckers catch up. Enough said: he has to be bookies’ favourite.

My personal tip is that 2015 will see Brown rain on a Daligault victory parade, taking one or two games off him, yet lose out once again, but by a narrower margin than last year.

Should a chess player be interested in Arimaa?

Musicology sometimes poses this problem. The 18th and 19th centuries appear to be jam-packed full of musical icons: Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Verdi, Wagner, etc. Yet clearly, this supply of geniuses started to dry up in the early 20th century, only to run out completely by the late 20th and 21st century. How could that have happened? Is the all-conquering 21st century composer as yet undiscovered, and quietly penning works of ineluctable beauty in Stoke Newington? Is classical music less popular, less studied, less remunerated? No, no and NO!

The reason why a 21st century Mozart does not exist is simple: he can’t exist. The 18th and 19th century musical giants got there first, and created and completed the genre for him. This project is over. There is nothing left to do: except to interpret and perform the output of earlier geniuses to ever dizzying heights of perfection.

In 2015, chess finds itself in a similar quandary. Does any knowledgeable student of the game actually expect new openings, strategies, concepts to emerge? Seriously? Or more likely, is our vision of the future that we are just going to see ever increasing refinement of existing material? More of the same: just slightly better. Does that excite you?

Here’s the dilemma. If you want to find a mental competition which is complex, intellectually and artistically satisfying and original you won’t find it in chess. Not anymore. And you are not going to fix chess, because that can only diminish the game.

In contrast, Arimaa does not suffer from over-research and offer opportunities for a creative spirit in all aspect of the game. Arimaa analysis is less susceptible to computerization. Yet it provides a competitive arena for the mind athlete. It’s fun to play and fun to watch. Moreover, it is an original discipline in it is own right: not a botched, derivative version of another (truly great) game.

Every chess player is recommended to take a look at Arimaa.

Appendix A: Arimaa – a Conversion Guide for Chess Players

The Armies

There are two Armies: Gold and Silver. Gold always goes first.

The Pieces

Each players Arimaa army has (in order of ranking)

- Elephant (x1)

- Camel (x1)

- Horse (x2)

- Dog (x2)

- Cat (x2)

- Rabbit (x8)

All pieces move in the same way: one-square forward, backwards or sideways. (Just like a King, except with no diagonal movement). The one exception to that is the Rabbit, which cannot move backwards (unless pushed or pulled by an opposing piece.)

Pushing, Pulling and Freezing

In Arimaa, you get the chance to move the opponent’s pieces. This can occur when your higher ranked piece is next to a lower ranked opposing piece. You can either “push” an opposing piece (you move your piece onto their square, the opposing piece moves away) or “pulling” the piece (your piece moves away, & the opposing piece moves into the square it formerly occupies).

Conversely, if a higher ranked piece is next to a lower ranked opposing piece (with no friendly adjacent piece), the latter is said to be “frozen”. However, pieces become unfrozen, just as soon a friendly piece moves next to them.

Captures and Traps

Captures as in chess (i.e. a piece lands on an opposing piece and the latter is removed from the board) are not possible. Instead, there are 4 traps on an Arimaa board (c3, f3, c6 & f6), and a piece is lost if it moves onto (or remains on) a trap where there are no adjacent friendly pieces.

Initial Position

Gold decides how to position his 16 piece army on Ranks 1 & 2. Then Silver does the same for his army on Ranks 7 & 8. Two common setups are shown in diagram 1. Generally, Rabbits are put to the side and back and Elephants to the front and middle. However, players are free to choose any set up they like (within their starting ranks).

Each Turn = 4 Sub-Moves

Each player’s turn consists of 4 sub-moves. The player is free to decide how these are distributed. So he could decide to spend his entire turn on moving his Elephant 4 times. Or he could decide to move 4 individual Rabbits once each. If an opponent’s piece is moved, this counts as two sub-moves (one sub-move for his piece and one for the opponent’s piece).

It is possible to “pass” for up to 3 of these sub-moves. The only constraints are:

a) The turn must change the position

b) The turn must not repeat the position (for the 3rd time)

Objective

An Arimaa game can be won in 3 distinct ways:

- Goal (your Rabbit reaches your opponents first rank)

- Elimination (you capture all of the opponents Rabbits)

- Immobilization (your opponent has no legal moves)

Draws

Not applicable. These are not allowed in Arimaa.

Appendix B: Arimaa Notation

Arimaa notation is similar to algebraic, but requires a brief explanation. The pieces are denoted by their initial letter with “C” standing for Cat and “M” for Camel. Gold pieces are signified with capital letters, Silver pieces by lower case. The grid reference following the piece symbols represents the starting point of the piece move. This is followed by the cardinal direction of each sub-move. So a move of the Gold Elephant from a5 to c7 would be written “Ea5 eenn”.

References

Websites

1) Wikipedia Arimaa: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arimaa – Rules, origin and history of the game, World Championships, and Arimaa strategies.

2) Arimaa Website: www.arimaa.com – Arimaa gaming portal and repository of all known Arimaa games, ever. Site is unrestricted and free to all registered users (and delightfully free of annoying adverts, pop-ups or web redirections!).

Books

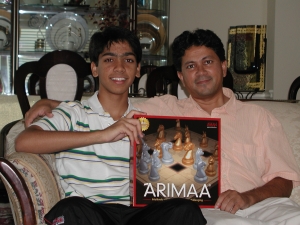

3) Beginning Arimaa: Chess Reborn Beyond Computer Comprehension (2009) – Fritz Juhnke (former World Champion) – highly readable introduction to the game, its origin and history, interspersed with witty philosophical observations on gaming and what makes games enjoyable and addictive.

4) Arimaa Strategies & Tactics (2012) – Jean Daligault (reigning World Champion) – the definitive work on the game.

5) The Middle Game in Chess (1952) – Max Euwe and Hiaje Kramer.

About the Author

Andy Lewis is a former British U21 Chess Champion, has a PhD in Philosophy, but spent most of his working career in computer departments for investment banks. He is semi-retired and lives with his wife and two dogs in Manningtree, Essex. He has played Arimaa for six months and is competing in the 2015 World Championship.

© Andy Lewis 2015

Also by Andy Lewis

Really interesting to read more about ARIMAA, thanks for the clear explanation. Good to know there’s an alternative to chess that computer programmes may not be able to master!

Can you explain or provide a link to information on the variant you mention: “Pawn-division (Regan)”? I can’t find anything for those terms with a simple web search.

Keith, you may find this link helpful http://en.chessbase.com/post/ken-regan-s-tandem-pawn-chess

“The 18th and 19th century musical giants got there first, and created and completed the genre for him. This project is over. There is nothing left to do” – where did you get this? It’s absolute nonsense.

Well, Mr. Adam P, I respect your opinion, and it’s certainly a debatable point. And to be fair, a composer friend of mine shot back a response to me as soon as the article was published, objecting to precisely the same comment as yourself. And, as if to clinch the argument, sent me an invitation to the premier of a work which he had recently composed!

But look at things in this way. Take a glance at the 2016 programme for Salzburg, the largest opera festival in the world. Consider the relative proportion of C20/C21 Operas staged to earlier works. Do the maths, and I think you’ll find the earlier works predominate by a ratio of 10:1. Or consider the largest classical musical festival in the world, the BBC Proms. The Proms makes a concerted effort to promote new works, but still the relative airtime of C20/C21 to earlier compositions is hardly even 20%.

So the reality is that for classical music, the vast majority of active practitioners and the fan-base are focused on, and appear entirely satisfied with, past achievements. Why do you think that is? Compare that with say, theatre or cinema, in which interest is equally balanced between the legacy and novel works.

But seriously, if you happen to have the name & address of the C21 Mozart, do write them into King Pin and we’ll be sure to be in touch!

There are simpler approaches. Chess history is replete with examples of rule changes to enhance the game of Chess. At the very least, we should ask ourselves what the impact upon existing Opening Theory etc. if pawns were allowed to move backwards one square at a time with zero other rules changes. If insufficient, increase complexity further by allowing rooks (Now 4.5 according to GM Larry Kaufman) to move one square diagonally. Finally, if necessary, begin the game only with pawns in place and on subsequent turns allow each player to place a piece on his or her first rank. Such changes are much easier to embrace.

Very interesting post! I liked it much! I read something similar in the blog of: https://www.albertochueca.com