Edward Winter bemoans the lack of pen-portraits in chess writing: ‘a highly demanding form of writing which requires no particular chess expertise yet is almost universally avoided nowadays’.

Chess writers are, with a few exceptions, chess experts rather than writers and rarely venture outside their area of expertise. Writers who are chess enthusiasts, on the other hand, have penned some sharp vignettes. Take Booker Prize winning novelist Julian Barnes on the Short v Kasparov World Championship match:

Short, a boyish figure in a bottle-green suit, with boffinish specs and cropped hair, cut a nervous, adolescent, halting figure, and spoke with the slightly strangulated vowels of one who has had speech therapy.

[Kasparov] handled the conference by himself and with presidential ease; was just as much at home with geo-politics as with chess; attended courteously to questions he was mightily familiar with; and generally came across as a highly intelligent, worldly, rounded human being . . . Short, by contrast, gave the impression of being thoughtful, considered, wise and precise when talking about chess, and barely adult when talking about anything other than chess.

‘TDF: The World Chess Championship’, Letters from London 1990-1995 (Picador, 1995), pp.260-1

Kasparov fizzingly coiled, scowling, frowning, grimacing, lip-scrunching, head-scratching, nose-pulling, chin-rubbing, occasionally slumping down over his crossed paws like a melodramatically puzzled dog. Short more impassive, bland-faced, sharp-elbowed and stiff-postured, as if he’d forgotten to take the coat-hanger out of his jacket. (p.272)

slumping down over his crossed paws like a melodramatically puzzled dog. Short more impassive, bland-faced, sharp-elbowed and stiff-postured, as if he’d forgotten to take the coat-hanger out of his jacket. (p.272)

There are also sketches of Speelman, Keene, Hartston, Divinsky, Crouch and others, and Barnes is especially strong on the language and theatricality of chess.

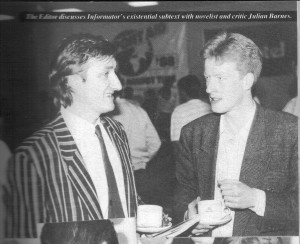

This photo was taken just after Barnes had been ‘slaughtered in a charity simultaneous by a fourteen-year-old’ (Matthew Sadler).

For more on this event which featured celebrities such as Stephen Fry and Greta Scaachi see Kingpin 14.

See also