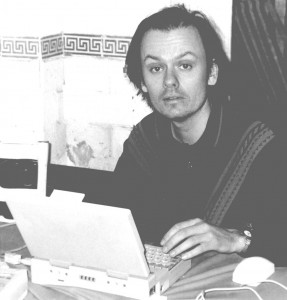

Stuart Conquest remembers his mentor

Our first address in Hastings was 11, Cloudesley Road. Some years later an acute economic squeeze forced us to sell that spacious abode, so instead we moved a few miles west, to a small semi-detached property high up on a hill, only accessible by footpath or, if you had the right change, chair-lift. This hill was more properly an embankment, beneath which ran the Hastings to Eastbourne railway line, so that one had only to negotiate a wire-mesh fence at the foot of our garden, struggle through a tangled mess of wild brambles, and skid down a near-vertical scree slope, in order to reach the glittering prize of the tracks themselves, at which point one would most likely be sliced to pieces by the thunderous London Victoria service, calling at all stations except Glynde and Polegate. (Change at Lewes for the Brighton line.)

A chess player needs to travel if only to find other chess players, and indeed the chap in charge of the ticket office at our local train station was one of the pillars of our little community. One October morning setting off on the way to the Guernsey chess festival I went with my father to this particular railway station (let’s call it West St Leonards) and asked for ‘a return to Guernsey, please.’ This was in the good old days, before computers took all the fun out of life. ‘Guernsey, you say?’ said the ticket man, hauling down all his British Rail volumes from the dusty shelves. ‘Now then, let’s see what we have here…’ and he thumbed through every timetable, fare directory, route indicator and map of the British Isles in his possession, scribbling down numbers, cross-referencing with something that said ‘Supplementary Notes: Important’, and all the while getting more and more confused. Finally he took a small pink ticket that had the words ‘From West St Leonards To’ on it, wrote carefully underneath ‘Guernsey, And Back’, and charged me five pounds. (When I arrived at Southampton docks I was the only person without a proper voucher for the boat, but with gentle insistence, and waving my pink ticket stub at all and sundry, I was able to make the entire trip without paying a penny extra.) As my train departed, the friendly ticket man said to my father, ‘You know something? I think I must have made an error there.’ That wasn’t the only time that he slipped up, and many people came from far and wide just to have the pleasure of purchasing their tickets at his window. He always stayed cheerful, even after they sacked him, and whenever we met in the street I would greet him with the words, ‘How much to Guernsey?’ to which he would reply with things like, ‘Aha! Guernsey! That’s a ripe one!’ and dig me in the ribs. A very sweet man, and sorely missed by all his old customers.

A chess player needs to travel if only to find other chess players, and indeed the chap in charge of the ticket office at our local train station was one of the pillars of our little community. One October morning setting off on the way to the Guernsey chess festival I went with my father to this particular railway station (let’s call it West St Leonards) and asked for ‘a return to Guernsey, please.’ This was in the good old days, before computers took all the fun out of life. ‘Guernsey, you say?’ said the ticket man, hauling down all his British Rail volumes from the dusty shelves. ‘Now then, let’s see what we have here…’ and he thumbed through every timetable, fare directory, route indicator and map of the British Isles in his possession, scribbling down numbers, cross-referencing with something that said ‘Supplementary Notes: Important’, and all the while getting more and more confused. Finally he took a small pink ticket that had the words ‘From West St Leonards To’ on it, wrote carefully underneath ‘Guernsey, And Back’, and charged me five pounds. (When I arrived at Southampton docks I was the only person without a proper voucher for the boat, but with gentle insistence, and waving my pink ticket stub at all and sundry, I was able to make the entire trip without paying a penny extra.) As my train departed, the friendly ticket man said to my father, ‘You know something? I think I must have made an error there.’ That wasn’t the only time that he slipped up, and many people came from far and wide just to have the pleasure of purchasing their tickets at his window. He always stayed cheerful, even after they sacked him, and whenever we met in the street I would greet him with the words, ‘How much to Guernsey?’ to which he would reply with things like, ‘Aha! Guernsey! That’s a ripe one!’ and dig me in the ribs. A very sweet man, and sorely missed by all his old customers.

The years spent at Cloudesley Road were to play a huge influence on my chess development, because two doors away lived Mr Arthur Winser, former Sussex champion, twenty-four times Hastings champion (!), and a man who had even participated in the Premier section at the annual Christmas Congress. Every Thursday evening, regular as clockwork, he would come over to the house and teach me chess, and this arrangement continued for the best part of five years, during which time I progressed enormously, while he became worse and worse. We both saw what was happening, and so from year six to ten I was giving him lessons, every Saturday afternoon, regular as clockwork, over at his house. Finally, after a decade of giving each other free lessons, we both got back to the levels which we had started with, called it quits, and paid some other guy to give us lessons instead. Twelve months later our new instructor died in a freak sewing accident. (Moral: you can’t teach your grandmother to suck eggs unless one of you keeps chickens.)

Let me describe a typical Thursday evening chess lesson with Arthur. We would always begin by looking at the four problem positions that he had left me the week before: two middlegames, and two endgames. I would offer my ‘solutions’, and he would offer his. I remember once winning a book prize at a junior event – It’s Your Move! was the raunchy title – and I started noticing that most of Arthur’s middlegame exercises came directly from that same work, so that for months I was scoring one hundred per cent on those two positions, although sometimes I would make out that I hadn’t seen a particular sub-variation, so as not to make things too obvious. My only excuse for this blatant cheating is that it did give me more time for working out some of his wickedly difficult endgame puzzles. God alone knows where they came from; I even tricked my father into buying me huge volumes of endgame studies, but I still couldn’t track down the damn things.

After that we’d go over an old ‘master game’; it might be a subtle strategic squeeze from a 1920s world title match, or a bloodthirsty massacre from the 1965 East German Championship. I was fascinated by the fact that a game played fifty or a hundred years ago could be exactly reproduced on my own chess set, that each decision, each threat and counter-threat, every last desperate pawn push could be replicated by my own men and by my own grubby fingers: it was possible to recreate an entire tournament just by following the quickly learned notation. And sometimes the players would tell you what they were thinking about! ‘I had set a fiendish trap…’ one would write, or ‘Naturally, I was ready to accept a draw at any given moment…’ It was living and breathing history on every page. The system that we adopted for coaching involved my father reading out one side’s moves, with Arthur and I trying to guess the replies; the write-down-your-nomination refinement was introduced because I kept on encouraging Arthur to say his move first, after which I’d heartily concur, and congratulate him on finding such a difficult continuation.

Some time during all this my mother would come in with cups of tea and coffee, and plates of expensive-looking biscuits which we would never normally have around the place, or else big wedges of blackcurrant cheesecake. The trick was to try and create confusion by placing your plate extremely close to someone else’s – making sure that you’d scoffed more of yours than they had of theirs – and then, while seemingly enrapt in the intricacies of Alekhine versus Znosko-Borovsky, casually reach out and help yourself to the larger of the two portions. Chess, like most mental disciplines, makes a great training-ground for life.

Some time during all this my mother would come in with cups of tea and coffee, and plates of expensive-looking biscuits which we would never normally have around the place, or else big wedges of blackcurrant cheesecake. The trick was to try and create confusion by placing your plate extremely close to someone else’s – making sure that you’d scoffed more of yours than they had of theirs – and then, while seemingly enrapt in the intricacies of Alekhine versus Znosko-Borovsky, casually reach out and help yourself to the larger of the two portions. Chess, like most mental disciplines, makes a great training-ground for life.

We’d finish up the evening with a quick game or two ourselves. Often I’d spend the whole week preparing for his Caro-Kann or Slav defences, then pause dramatically over some positional exchange sacrifice that I’d spotted in an obscure footnote in Modern Chess Openings, or else feign disgust and disbelief after ‘accidentally’ leaving a pawn en prise on move fifteen, refuse to take the move back, and after he captured it sink into a profound reverie, before unleashing a ten-move combination leading to mate or win of the queen, all courtesy of New Traps in the Slav Defence – Second Edition. (He only had the first edition.)

And so it went on. Arthur became a friend of the family, and one day my father even persuaded him to let him paint his portrait. My father has never claimed direct descendence from Rembrandt or Titian, which is understandable if you’ve seen any of his work, but the painting was not bad at all, and Arthur was highly flattered.

Winser v Wood

Hastings 1949

White to play

When I was still only nine years old I managed to qualify for the final of the Hastings Club Championship, which was some kind of Club record. The then tournament director, Charles McLeod (presently living in a tree in Australia, according to some sources) was kind enough to say, in the Hastings Observer of Saturday, 8 January 1977, that: ‘He is not only the best player of his age in the town, but, in my view, he is probably the best in the country.’ I proudly pointed this piece out to my parents, and my father said that he had obviously said ‘county’, but the paper had decided to change it. (A hyena on stilts could scarcely elicit such belly-laughs as do my father’s rich ripostes.)

‘Arthur was even buried with a tiny fold-up chess-set inside his jacket pocket, all ready for his final journey’

When I was ten I won a 30-minute tournament at the Club with 4.5/5, and collected the first prize of nine pounds. It was then that I realised that if I devoted the rest of my life to playing chess then I would surely die a very rich man indeed. We all make mistakes.

When I was eleven I was photographed playing chess with two Russian Grandmasters who had come over for the Premier tournament that year, a Mr Vasyukov and a Mr Kochiev. It was only a friendly game for the cameras – I was hardly looking at the board – but after the press people had all departed they insisted on playing the game out to a finish: it was a humiliating and singularly degrading experience. The next day the caption in the paper was ‘Russians Help Chess Boy.’ Many years later in Denmark I played a proper tournament game with Mr Kochiev, and he did seem like a perfectly nice man after all. But he still crushed me.

At twelve I achieved ever-lasting fame and glory by finishing first equal in the Hastings Club Championship. The co-winner was my good friend Patrick Donovan, who was a sprightly 16, and whom I held as a paragon of all that was noblest and most virtuous in this Royal Game. (Over the years I was to gradually see other sides to Patrick’s persona, such as when he started wearing funny hats, or when he would put on a strange accent and say, ‘Not in these trousers!’ in reply to whatever question you asked him.) Since Patrick had also covered himself in fame and glory, and since we were scared of each other, we chose to break with Club tradition, and agreed to share the title of Champion. In later years the two of us co-invented that familiar household game, ‘Knightrider-Bouncy Chess’, and held official Challenge Matches at secret locations in Bexhill-on-Sea. Patrick was the first World Champion, but was dethroned by a certain Raymond Brooks, who then ran off to join the Army. I had to give the thing up, after repeatedly analysing Knightrider-Bouncy moves during serious chess games.

My thirteenth year was an unexceptional one as far as chess was concerned: for the first time in my life I had to struggle with the physical and emotional problems of being a teenager. (For bad acne read bad bishops. Also I fell in love with a dinner-lady.)

All those long years of careful study finally paid off at fourteen, when by some unique blend of luck, chance, and sheer good fortune I managed to emerge victorious at the World Cadet (Under 16) Championship, held that year in Argentina. But that’s a story for another time.

Granda Zuniga v Conquest

World U16 Ch, Embalse 1981

Black to play

In May 1987 my family and I moved to Bristol, although my sister still lives in Hastings, and I almost always go back to the town for the annual Christmas Congress. There are many other little anecdotes about the Hastings Years which merit inclusion in the annals of history, and since no-one else is likely to recount them I suppose that I’ll have to do it … but not right now. (Relax: I’m working on the screenplay.)

In June 1991 I made my final Grandmaster norm at a tournament in Paris, the last staging-post in gaining official recognition for the title. I arrived home full of glad tidings, but my mood changed completely when my parents told me the sad news: Arthur Winser had died a few days earlier. He was 84 years old.

I attended his funeral on behalf of the whole family. Just about every member of the Chess Club was there that day. Arthur was even buried with a tiny fold-up chess-set inside his jacket pocket, all ready for his final journey. Just as the service was about to begin I looked up and saw a familiar car arriving: my father had decided to come after all, and had driven down from Bristol that morning. In the back seat was the picture that he had painted of Arthur all those years before.

Later we had a quiet reception at the Chess Club. Most of the boards and sets had been cleared away, and a notice had been put up that said: ‘No chess today’, but this didn’t seem completely appropriate, so Mark Rich and I played a few casual games, but only in Arthur’s favourite old openings: the Caro-Kann and the Slav. My father stood his painting up on the mantlepiece, and one Club member, now also deceased, said what an awful picture it was, and how it didn’t look anything like old Arthur, although to be fair I don’t think he realised who the artist was, or else he might not have been so judgmental. And that same work of art can still be viewed in Hastings Chess Club to this very day.

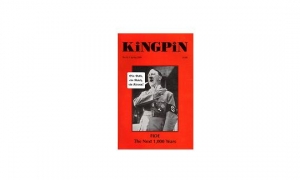

First published in

I have been searching for that very same Charles McLeod for many years – a very close friend whom I’ve been unable to find due to both of us moving house, and losing my wallet with the only contact details (address of his offspring somewhere in Kent or Sussex) The last tree I saw him living was quite a comfortable one in Brisbane, but 15 or more yrs ago. If alive he’ll still be playing chess so I hope sooner or later a chess player will help me unearth him.

I asked the British Chess magazine if they would print a missing person ad in their classifieds but got a snooty refusal. Cheers. Like your article by the way.

Pete Hewlett, Adelaide