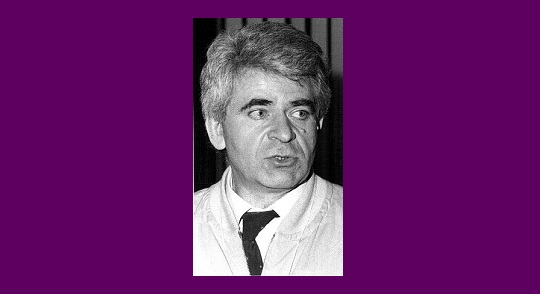

Lev Khariton

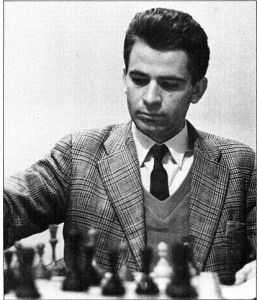

The attractive countryside of Meudon is a 15-minute train ride from Paris. Here I came to interview Boris Spassky just three days before his 60th birthday. He reminiscences about his life, his chess career, his rivals and friends.

Dear Grandmaster, I should like, as many other chess players all over the world, to congratulate you on your jubilee and to wish you good health, all possible success and creativity.

Thank you for the congratulation, but what success and creativity are you talking about? All my achievements are in the past, and the last time I played well was the Montpellier Candidates in 1985. If it were not for some physical indisposition at the very end of the tournament I should have qualified for the quarterfinals.

Why did you stop playing in tournaments?

I felt that I had no more energy to play, that I had lost any desire to win. I remember that I won the first prize in Linares in 1983 leaving Karpov behind. At that time I was already living in France, but I was still playing under the Soviet flag. Karpov was evidently furious, and soon afterwards the Soviets took away the red flag from my table; what is more, they deprived me of my stipend from the Soviet Sports Committee. These 250 roubles I needed very much to help my family in Russia – my mother, my brother and sister, my children.

But the Sports Committee seems to have been ‘cool’ to you long before the Linares tournament.

Well, I was the first to show how to fight against the Soviet bureaucrats and at the same time to continue professional life. Now everybody knows how to do it, but at that time I was the first, and, naturally, the Soviets could not forgive me. With Korchnoi they had no problems: they knew that he would make a lot of fuss, but then some Soviet guy would win and in the end things would turn out OK for the Russians and everyone would be happy. As for me, from the very start I took an independent stand and openly declared that I did not want anything from the Soviets.

Karpov once said that in chess there are no ex-World Champions; there are only World Champions. For example, we never say ‘ex-Olympic Champion’. This title is awarded for life. How can we, for instance, call Alekhine ‘ex-World Champion’ if he died undefeated? And all the other chess champions are chess kings for ever…

I think in this case, as usual, Karpov was thinking of himself, but in principle what he said is absolutely right. The title ‘ex-Champion’ does not reveal anything, and some time ago I proposed to use the number before the title of each champion. For example, I was the 10th World Champion, Tal the 8th World Champion etc. This makes much more sense.

Not much is known about the beginning of your chess career. Everyone in this world has a destiny. You, for example, could have become an engineer, a teacher, a doctor. . .

Well, I got to know the rules of the game during the war when I was far away from Leningrad. Soon after the outbreak of the war I and my elder brother (he is two years’ my senior) with other children were evacuated from Leningrad. I was lucky to survive; the people in Leningrad, as you know, were starved to death. On the way to the Urals our train was heavily bombed several times. Finally, we arrived at Perm where I was placed at an orphanage, an extremely beautiful building on the site of an old convent. Years later the convent was pulled down on the order of Khruschev. Nobody taught me to play chess there. I was just watching other people playing chess. At that time I was only five years old. Upon our return to Leningrad my brother took me to the Kirov Isles (near Leningrad – LK) and there I saw a chess pavilion. It was 1946, I was only 9! The pavilion was a glass veranda surrounded by trees, and I was really captivated!

Did you begin to play with grown-ups at once?

No. At first I was only watching. I was infatuated with the world of chess. I left home early in the day and returned late at night. My mother gave me 15 kopecks to buy a glass of water and a small pie. We lived in stark poverty, but I had such a passion for chess that I never felt afterwards. Actually I became a chess professional at the age of ten. Looking back, I had a sort of predestination in my life. I understood that through chess I could express myself and chess became my natural language.

Did you have chess trainers, let us say, like Kasparov used to in his childhood?

At first I was alone, but the chess pavilion had closed by the autumn, so I had no place to play chess. Therefore in November 1946 I went to the Leningrad Palace of Pioneers, where I met Vladimir Grigorievich Zak. He was a remarkable trainer and a wonderful man. I remember that my mother gave me her soldier’s boots. She used them when she was harvesting potatoes to feed the family. So in these boots which reached up to my stomach I went to the Palace of Pioneers. Zak saw that I was a serious boy, and he loved chess immensely. He died quite recently. I am very grateful to him and I am helping his family now. As you know, the government does not help people now, the poverty is frightening and who can help poor people? In general, I was lucky because I met many good people in my life. I always remember Tolush, Levenfish, Bondarevsky… I recall that when I was having my first chess sessions with Zak, I wanted very much to steal a white queen so as to caress it in my pocket! It was just a childish passion. In retrospect, I think that if I had stolen it I should have never become World Champion!

In other words, you mean to say that stealing a chess piece would have been a bad omen. . .

Not so much a bad omen, but simply that one must be honest; that is why when I became Champion I said that chess is a game of Justice. Supreme justice, may be… I would say that chess for me has always been a model of life. But as to justice, at the top level chess is a devilish game – just look at the faces of chess players! But the laws are the same as in real life, and once you violate them, sooner or later you will be punished.

Boris Vassilievich, the chess world has always respected you for your independent views, the freedom of your self-expression; for example, you always sympathised with Keres and Estonia, you did not sign the notorious letter against Korchnoi. . .

I have never signed ‘team letters’…

You were not afraid to speak about Solzhenitsyn when his name could not be even whispered.

Since you have mentioned Solzhenitsyn, quite a funny story comes to mind. Once, when I was World Champion, I was invited to one small town to give a lecture and a simul. I was speaking about my salary. For instance, I said that I did not have enough money to pay my trainers, that my work as a trainer was a sinecure, etc. Suddenly one of my listeners asked me which writers I liked. I answered that one of my favourite writers was Solzhenitsyn. After the lecture I was told that just the day before the party bosses of this town had been ordered by Moscow to launch an ideological campaign against Solzhenitsyn! And, naturally, a secret report denouncing me was sent immediately to the KGB. But the most curious thing about it was that in the report he sent to Moscow the party secretary of this town did not even mention my words about Solzhenitsyn! He wrote about my complaints concerning my miserable salary, about my irresponsible attitude to work, etc. He even mentioned that I was proud of my grandfather who was a famous priest in Russia. During the lecture I said that if I had not become a chess player, I should have preferred to be a priest. But there was not a single word about Solzhenitsyn in this dirty letter. So great was the fear!

You said that you have lost a taste for the game. But about Korchnoi, who is six years’ your senior? Or Smyslov, who is playing very well at 76?

Smyslov is a chess player with a fantastic intuition. I call him ‘Hand’ because his hand knows exactly on which square to put which piece at a given moment; actually, he does not have to calculate anything. As for Korchnoi, I regard him as an exceptional grandmaster in chess history. Usually the chess player reaches his peak by the age of 30. Viktor was, I believe, at the height of his form when he was playing against Karpov in Baguio in 1978. That is, he was 47 years old! The secret of his chess longevity is simple: he has been working on chess all his life, more than anybody else in the world! When he was living in the USSR I called him ‘hero of socialist labour’; when he moved to the West I renamed him ‘hero of capitalist labour’!

Recently I wrote an article on the inflation of the grandmaster title. But your generation, let us say, Korchnoi, Stein, Polugaevsky, were grandmasters par excellence. . .

I remember how in the USSR Championship in 1961 before I was to play Leonid Stein, who was at that time a master, Korchnoi came up to me and proposed to prepare me for this game. I do not think that he was sympathetic towards me; he just did not want the grandmaster title to be within easy reach. He wanted to check to see whether Stein really deserved this title.

As far as I remember, you lost that game to Stein – just as you had lost to Tal in 1958. These were serious setbacks for you; for some period you were obviously off form and you were put off the struggle for the chess crown. How can you account for this sudden streak of failures which surprised the chess public at the time?

The explanation is absolutely simple. My life did not pan out properly. I went through two divorces – there is a joke that two divorces are tantamount to participation in one war! My health also left much to be desired – I was suffering from kidney trouble, that returned in the second match with Fischer. Besides, at that time the Soviet Championships were usually held in January and this was quite unfortunate for me since these important tournaments coincided with my exams at the Institute.

So, you were not a chess professional, you were studying quite seriously. . .

As a student I had a stipend – 35 roubles; and this sum was the only source of subsistence for me. There was nothing and nobody to lean on.

Since we mentioned Tal, what were your feelings after you had lost to him the decisive game in the USSR Championship in Riga in 1958 and therefore failed to qualify for the Interzonal tournament? I remember that I was almost crying because I wanted you to reach the World Championship. Moreover, Tal, everybody’s favourite, did not need this victory as he had already scored enough points to ensure qualification for the Interzonal.

I shall tell you a wonderful story. After my loss to Tal I went out into the street, I was absolutely depressed, tears were running down my cheeks… Suddenly, while walking I met David Ginsburg, the journalist who had worked in the chess newspaper 64 before the war and was later sent to the GULAG. ‘Is it worth being so upset?’ he asked me. ‘Well, Tal will play his match with Botvinnik, and he will win the title. But later he will lose the return-match to Botvinnik. Some time later Petrosyan will become World Champion, and then your turn will come…’ Such an accurate forecast, better that any fortune-teller! I should say that I always had very good relations with Misha Tal – not a single shadow throughout many years. Although we were always fighting fiercely over the chessboard and in 1965 we even played a Candidates’ semi-final. Misha is the only one of the great chess players who did not know the feeling of envy. He was at his best when the initiative was on his side. In closed positions, without initiative he felt suffocated. In this respect Kasparov resembles him very much today. If Kasparov loses the initiative, he immediately accepts the draw. Tal was a real magician, his appearance on the chess horizon was an explosion, a challenge to Botvinnik’s dogmas…

Does this mean that your attitude to Botvinnik is negative?

Bovinnik did a lot for chess. He won the World Championship, as he had promised, he gave a lot of good advice to chess players, especially mediocre players. But for me he has always remained a Bolshevik. Once I was reading his memoirs about the 1930s and I came across the following sentence: ‘Life was difficult, collective farms had not yet become strong…’. For many years after this I wanted to ask him, ‘Mikhail Moiseyevich, when did collective farms become strong? And how did they become strong?’ I think in this respect Karpov and Kasparov continued Botvinnik’s Communist traditions.

Timman once said that, for example, in 1973 a match between Tal and Fischer would have been most interesting. By that time Tal, having regained his form, won a series of impressive victories.

I don’t think that Tal was much of a match fighter. I think that much earlier, in 1962, a match should have been organised between Fischer and me. Bobby was already a very strong player at that time. And, certainly, it can only be regretted that in 1975 there was no match between Fischer and Karpov. This is one of the so-called ‘unplayed matches’ for the chess crown.

As Lasker-Rubinstein, Alekhine-Botvinnik. . . And what would have been the outcome of such a match?

Probably, Bobby would have won by a narrow margin. Karpov was already very strong. The openings would have been of great importance in that match; Fischer would undoubtedly have sought a complicated game and avoided, say, the Exchange Variation of the Ruy López.

To what do you owe your success in the 1960s in surpassing the strongest chess players?

In the USSR at that time there were six chess players who were evidently stronger than all the others: Petrosyan, Tal, Stein, Korchnoi, Polugaevsky and me. I think that I was stronger than the others in the middlegame. I had a very good feel for the crucial moments in the game. This made up for certain deficiencies in opening preparation and, possibly, some flaws as regards endgame technique.

But doesn’t that contradict the basic idea of the Soviet chess school that the opening, the middlegame and the endgame are inseparably linked?

The Soviet chess school is a myth or, rather, a demagogic weapon, as many phrases being used today, for example, ‘new democratic thinking’, ‘new economic space’, etc. There was Botvinnik, he actually created himself and the word ‘school’ was used for ideological purposes. As for my games, I often won in the middlegame, so you cannot find too many endgames among my victories!

I wish you would say a few words about your matches with Petrosyan. Which was more difficult – the one you lost in 1966 or your victory in 1969?

The second match was no doubt more difficult since I was feeling more responsibility. Already before the first match I understood that I was stronger than Tigran. But I was exhausted by the qualifying competitions and, besides, I was a penniless man. And when a poor man becomes the king (by my convictions I am a monarchist) disaster may befall the kingdom. I remember during the first match that each time I went down to the snack-bar I saw a slogan hanging up on the wall: ‘The donor is the sick man’s best friend!’. So the whole match was always associated in my mind with this stupid slogan. When I was playing the second match I already had some money, so that I could pay my trainers. Not long before I had won 5,000 dollars at the strong Piatigorsky Cup in Santa Monica. By the way, during my first match with Petrosyan Smyslov saved me from starvation: he often invited me to his house for dinners, so that by the time I had lost the match I had gained six kilos!

What could you say about Petrosyan?

Not long before his death Petrosyan said to me: ‘Look what these guys, Karpov and Kasparov are doing! Do you remember how we signed our match contract on a window-sill in Moscow’s Sophia restaurant?’ Well, good old times! Petrosyan was an extremely intelligent man with a special sense of humour. He was a self-made man. Once he told me about the time he and Korchnoi visited Pavlov, the then president of the Soviet Sports Committee. Petrosyan sought Pavlov’s permission for Korchnoi to be his second in the match against Fischer. And Korchnoi with his characteristic straightforwardness blurted out: ‘Comrade Pavlov, when I see Petrosyan’s awful, disgusting moves, I don’t want to help him!’

Yes, Korchnoi has always been too straightforward. . .

But Tigran was happy: he did not want to have such a second. I came to know Petrosyan very well. He was just an open book for me. He was a hot-tempered man. When he was walking quietly I knew that he was about to jump like a panther; on the contrary, when he was moving like Napoleon it was always a sign of cowardice.

Let us get back again to bygone days. The tournament in Bucharest in January 1953… For the first time the chess world heard your name. As if using the Time Machine I am returning to the distant past: I am sitting at home with my elder brother analysing your victory against Smyslov. To tell the truth, I did not know chess notation well at the time…

This was my first trip abroad to a chess tournament, and it was in Bucharest where I made the International Master’s norm. Paradoxically, it was Soviet Power that helped me win the title! The tournament started with the ‘massacre’ among the Soviet chess players. Petrosyan won against Tolush, I defeated Smyslov, and after the 7th round Laszlo Szabo was leading the field. Suddenly there came a telegram from Moscow ordering us to stop shedding our own blood and insisting that we should draw all our games between ourselves. Luckily, I had already scored a point against Smyslov, but I think, taking into account my youth and lack of experience, that it would have been difficult for me to make draws with such grandmasters as Boleslavsky and Petrosyan. However, this order from the Kremlin helped me, everybody obeyed it and so I became an International Master.

It was January 1953. ‘The doctors’ case’ instigated by Stalin. Were you aware of what was happening in your country?

No, I was not yet 16, and I was living in another dimension. But two years later during the junior World Championship in Antwerp I did not find anything better to ask Mr. Solovyov, who was the head of our delegation, than whether it was true that Lenin had died of syphilis. Besides, I enquired why in Belgium, where nobody studied Marxism-Leninism, people were leading a prosperous life.

Boris Vassilievich, whom could you single out as a personality among chess players?

Undoubtedly, Paul Keres. He was the greatest treasure of the chess world. Being a man of great modesty and tact, he possessed the highest chess and general culture. His tragic destiny reminds of the end of Alekhine’s life. And if we remember that for some time there was chess rivalry between Alekhine and Botvinnik, I’d rather resort to some literary comparison. Keres was the Gulliver among the Lilliputians, he was a real giant. Botvinnik, I believe, was the leader of the Lilliputians. And that is the crux of the matter. As simple as that.

You always expressed sympathy towards Keres openly, even in the most ‘silent’ times.

In 1965 I was giving a lecture in Novosibirsk and I was asked why Keres had not become World Champion. This is what I answered: ‘Just imagine a young man who is only 24, who is already a strong grandmaster and who loves his Estonia, his small country which within a short period of time changes hands – passing to Stalin, a bit later to Hitler and again to Stalin. What does he feel when all this is happening?’ After the lecture some comsomol leaders asked me why I was so anti-Soviet. ‘Did I tell you a lie?’ I reiterated. But it was too late; my KGB file had already been opened.

In your opinion, which period was the peak of your chess career?

I think that I was the best in the world from 1964 to 1970, but in 1971 Fischer was already stronger.

So, now we have come to Bobby Fischer, possibly the most enigmatic player in chess history. You have played with him more than anybody on Earth and it would be nice to hear you speak about him.

Bobby has always impressed me by the integrity of his personality. In chess and in life. No compromises! If, for example, he faced the possibility of a triple repetition in an inferior position, he would always deviate, even at the risk of losing the game. Once he was approached to advertise a Volkswagen car. But he refused to do so saying that after having carefully examined the model he decided not to advertise the car to would-be suicides.

Before the second match with Bobby you said that he had saved you from complete oblivion, but it seems to me that it was owing to you that he came back on chess track.

Certainly, I did something to wake him up, but he woke me up as well.

When you were playing the second match with Fischer, did you want to win?

No, I did not have that ambition, but I had a good fighting spirit.

Many specialists preferred the games of your match to those played in the Anand-Ivanchuk match which was being held at about the same time.

Yes, we played quite a number of nice games.

However, there was an impression that Fischer was a bit rusty after such a long chess hibernation…

He has simply lost energy.

Was he studying chess all these years?

I think that his chess studies were mostly of an amateurish character; he did not have a sparring partner; may be from time to time he toyed with a computer.

What was Fischer’s trump card in chess, and did he have any weaknesses as a chess player?

Fischer’s strength, among other things, was his ability to evolve the most efficient plan for the middlegame right after the opening. I was amazed during our second match that he was spending more time than me. He needed a plan, a clear-cut plan for the game. At the same time he has a computerlike approach to the game. He thinks that in chess it is necessary to advance a bit all the time. But chess is like life: one must know how to retreat. Just to retreat a bit, to accumulate something and to advance again…

Even today your first match with Fischer is still fresh in the memory. I remember how the world was waiting for this match, how chess players were following every game…

Fischer made short work of me. Tal was right when he said, ‘There was no Spassky in this match’. I had actually lost before the match. My nervous system was completely broken. The Soviets were bothering me, and I also made my life difficult. Both Fischer and I were fighting windmills!

After the first two games you were leading by two points. Bobby did not turn up for the 2nd game after quarrelling with the organisers.

After the 2nd game I could have returned to Moscow. There was only one way I could have won this match: before the 3rd game, when Bobby raised a scandal with the organisers, I should have resigned this game.

But that sounds quite absurd!

Why? I was about to do so, but I was the Chess King and I could not go back upon my word. I had promised to play this game. As a result, I destroyed my fighting spirit and the match which promised to be a great chess feast turned into a litigation. Some days before the start of the 3rd game I spoke for half an hour on the telephone with Pavlov, president of the Soviet Sports Committee. He demanded that I should declare an ultimatum which, I was sure, Fischer, Euwe and the organisers would have never accepted; so, the match would be broken off. The whole telephone conversation was just a never-ending exchange of two phrases: ‘Boris Vassilievich, you must declare an ultimatum!’; to which I responded, ‘Sergei Pavlovich, I shall play the match!’ After this conversation I spent three hours in bed shivering with nervousness. Actually I saved Fischer when I agreed to play the 3rd game. So, the match was practically finished after this game. In the second half of the match I simply did not have the energy. A chess player in such a match is like a car which has too little fuel left. And if you have to go 500 kilometres with practically no fuel, where will the car take you? Unfortunately, most of the chess public is not aware of it.

What about Fischer? What is he doing now?

We are friends, and I think that I have no right to say what he does not say himself. You surely know that now Bobby lives in Budapest. If you take into account that there is the ‘new world order’, the KGB is not, for the time being, bothering him.

Grandmaster, let us speak now about the situation in today’s chess kingdom.

Well, since you are talking about the chess kingdom, I recall the following episode. After Petrosyan had defeated me in 1966, he invited me to the Armenia restaurant in Moscow. Many people, mostly writers, journalists and actors, came to celebrate Petrosyan’s victory in the match. Looking at all those present I raised a toast in Tigran’s honour saying: ‘Before the match I thought that the chess world was a republic, but now I am sure that it is a monarchy.’ To tell the truth, I had no doubts at that moment that I would play Petrosyan in 1969 and become World Champion.

But considering what is happening in the chess world today, it is difficult to say whether it is a monarchy, a republic… Is there any democracy in the chess world? There are two champions, FIDE, PCA [this interview took place in 1997, before the demise of the PCA]… Who is calling the shots?

First of all, I repeat that the chess world is a monarchy. But the two chess geniuses Karpov and Kasparov, strange as it may seem, are not chess kings. There is nothing royal about them. They are simply representatives of enormous chess teams; more than that, they are just mouthpieces of political parties. As to their personalities, their views as regards life, politics, all that is happening in the world, I cannot properly judge. As far as my political views are concerned, I am a Russian nationalist, and their views are naturally different from mine.

But many people believe that Karpov, one who so typified Brezhnev’s era, has undergone a certain evolution of late.

After the publication of Karpov’s book My Sister Caissa I said to him, ‘If you believe in God, Caissa cannot be your sister. At best, she can be your cousin!’

And how did Karpov react to your words? Did he laugh?

Certainly, not. We are absolutely incompatible.

Not long ago there was an interview with Karpov in Liberation in Paris. When he was asked about his contribution to chess, he answered: ‘I am part of chess history.’

Modesty is not his strong point. But we must pay him his due: as a chess player, he is great.

Incidentally, two years ago in an interview also published in Liberation Kasparov said that his favourite historical hero was Julius Caesar.

Probably, he believes that he, like Caesar, can do a host of things at the same time…

Karpov does not recognise Kasparov as World Champion and recently his statement was published in the Russian Magazine 64 that a grandmaster playing outside the auspices of FIDE cannot be considered World Champion. What is your point of view?

At the moment Kasparov began the destruction of FIDE he created the ‘new’ World Champion! So, it’s up to both champions to decide which of them is the real champion. One thing is, however, clear for me: if they had really played honestly 150 games in the five title-matches, both of them would have been in a mental asylum. Undoubtedly there was some kind of conspiracy between the two champions, probably starting with their third match. At least that was my impression when I was working as commentator of their match in Lyon in 1990. I shall never forget the 19th game when Kasparov proposed a draw in an absolutely winning position while Karpov was in awful time trouble. I was in a state of shock, absolutely unable to explain to the chess fans what had happened in this game. Now in retrospect I understand that mysterious, powerful and super-wealthy forces were standing behind their backs, and the two guys could have risked their lives had they disobeyed… I remember, for example, that after I had won against Petrosyan in 1969, it took me one year to return back to normal. I was completely exhausted after 23 games, but Karpov and Kasparov played five long matches! If they had really invested all their forces in all the games of all the matches, both would have been mentally sick for years. There was certainly some conspiracy between the players, they won a nice sum of money and kept their health in good shape.

Just one last request: say something, if only in jest, about your relations with the chess world.

Well, I remember an episode from Ernest Hemingway’s novel To Have and Have Not. An old toreador is about to retire and draw his pension. His friends have organised a present for him. They take off a big sheet covering the present and the toreador sees the enraged head of a bull. He turns deathly pale and it becomes clear that all his life he has been afraid of the bulls but never stopped fighting and winning!

But you, I am sure, were never afraid of anyone…

That’s right. I was afraid only of myself.

First published in Kingpin 29 (Autumn 1998)

Totally fascinating. I think this is the most substantial interview with a chess player I’ve ever read.

We’re often led to believe that the Soviets dominated chess because the government gave the players so much help. But Spassky claims to have had a pretty hard time.

He makes some strange remarks:

I find it hard to accept Botvinnik being described as merely “the leader of the Lilliputians” in chess terms! Perhaps as a person he was Lilliputian, a lousy Bolshevik, I don’t know.

Spassky’s remarks about Karpov and Kasparov are very strange. It seems that personal feelings are too strong at the top in chess for Spassky to make rational remarks about other world champions. Other top players also suffer from this weakness.

Hard truth and very frank speaking from a living legend of chess. We all will remember spassky not only as a world champion but also as a nice and friendly human being.

You really created quite a few good ideas within your article,

“No Regrets: Boris Spassky at 60”. I will

remain returning to your blog before long. Many thanks -Chante

A truly outstanding interview by a remarkable human being and an exceptionally underrated World Chess Champion.Anyway , one can easily conclude that Keres’ games are worth studying.

Boris Spassky was born on 1/30/1937,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boris_Spassky,

So HOW CAN HE BE 60 in 2007 ? He will be 78 in 2015, should be 70, probably, just a typo !

The interview first appeared in Kingpin in 1998 (as shown at the end of the post), so the title was correct at the time of publishing. It was posted on the website in 2007.

I learned a lot about the entire history of chess under the Soviets from this article! This is incredibly eye-opening. Thank yo U!

Great article, Lev. Thank you.

A very interesting interview – Spassky is a fantastic man. I can still remember how strongly he played in the 1960s, not least in the Candidates matches. He gave an equally interesting interview to Leonard Barden after his win against Petrosian 1969 (published in Chess Life and Review in 1970 as far as I remember).

Thanks for sharing this with us.

You are very welcome. Andrew Soltis has some excellent material on Spassky’s early years in his ‘Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi: A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games’.